When the old man swung the imaginary bat through the fresh air of a clear, sunlit afternoon, the weight and dust of all the years fell away like marbles toppling off the edge of a three-legged table. Adults clapped. Little kids hung from the rail and sat atop a parent’s shoulder. Some men and women, of a certain age, and with a certain look to them, even cried.

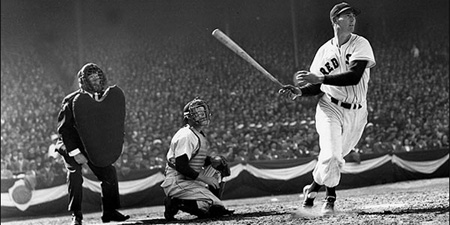

The swing was still smooth as tap water tumbling from a faucet on the hottest of August days. The hips turned perfectly and the huge hitter’s hands rolled right over. The bulk of seven decades didn’t even show through the old man’s sports jacket because all anybody really saw was the number 9.

It seems odd, maybe even sacrilegious, to call him an old man because he lives beyond any calendar. Birthdays do not matter. When you are Ted Williams, nobody adds up the years.

I first saw Ted Williams in 1951. He was part of a pretty good team that could never quite catch the Yankees. When I shut my eyes, his swing at Fenway Park Sunday is the same swing I recall across all the vanished decades.

I first met Ted Williams in 1953. It was the year he returned from Korea. He did not have post-traumatic stress disorder. He did have 13 home runs and, once in awhile, if you waited long enough, you could catch him behind the old Somerset Hotel on Commonwealth Avenue.

In those days, I had very little idea what he might be doing inside the Somerset. Eating there? Living there? Who knew? All I knew was that rumor was the currency of youth and if there was even a whisper that Ted was around the hotel, the stakeout for autographs would begin.

There was no television then. Drugs and guns were unheard of to us, perhaps preposterous myths to older people. The few gangs that did exist were a collection of unemployed guys with duck-tail haircuts and pegged pants. Parents let kids ride trains, buses and trolleys around town with not a second thought given to safety.

We would go the ballpark in clumps. Sometimes we’d go to Braves Field, but more likely it was Fenway because that’s where the greatest hitter in the history of the game lived.

And Fenway became our church. Just as there was a downstairs 8 o’clock children’s Mass each Sunday in the parish, there was mandatory seating at the park: As close as you could get to the sloping left field rail where No. 9 prowled below.

He was then — and is now — larger than life. Unlike so many others — politicians, actors, statesmen, teachers, scientists, war heroes — time has not shrunk or sullied Ted Williams.

And Sunday, when they commemorated the fact that it is 50 summers since he hit .406 (and since Joe DiMaggio hit safely in 56 straight baseball games), you could hear the ballpark talk. Oh yes, ballparks do have voices, and they’re filled with memory and emotion.

I heard it. I think a lot of others did, too. And I’m sure Ted Williams heard it because it nearly caused him to cry in full view of all those strangers.

The ballpark spoke about The Kid from San Diego who hit .400 in that year of lost innocence. We were on the threshold of a war that would change America forever but, back then, baseball was our best seller, a story people bought and talked about every day, a tale told from radios perched on a thousand windowsills as a million men, women and children gathered on stoops and porches, following the action.

Ted Williams is that time. Ted Williams is that country. Other heroes have come and gone. The violence of the brutal years defeated a lot of dreams, but Ted Williams remains. Still looking like . . . well, Ted Williams.

Why has he survived? Simple: He could do whatever it was that needed to be done. You need a guy to hit .388 with 38 home runs? No problem. You need a man to sit in the cockpit of a fighter plane and protect democracy? You need someone to make sure John Glenn doesn’t get killed in Korea before he flies into outer space. Are you looking for a straight-talking, truth-telling, uncomplicated, no bee-essing, get-it-done, old fashioned, can-do, American kind of guy. Meet No. 9.

Baseball is a funny thing. It’s bigger than just a game. It has all these memories and stories attached to it, which makes it truly unique. Who tells football or basketball stories? What kid really has an indelible hockey memory?

Sunday, you could see — really see — through the fog of those long-gone summers. And you could hear — absolutely hear — the ballpark talk when Ted Williams stepped to the microphone, The Kid come home.

Then he took that swing. Spoke a few words. Tipped his cap. Glanced around, eyes repelling tears of current gratitude and nostalgic regret. There he was, legend married to magic: Ted Williams, up there for all the kids who ever were. He is the man who made summer last forever.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction or distribution is prohibited without permission.

Abstract (Document Summary)

I first saw [Ted Williams] in 1951. He was part of a pretty good team that could never quite catch the Yankees. When I shut my eyes, his swing at Fenway Park Sunday is the same swing I recall across all the vanished decades.

Ted Williams is that time. Ted Williams is that country. Other heroes have come and gone. The violence of the brutal years defeated a lot of dreams, but Ted Williams remains. Still looking like . . . well, Ted Williams.

Then he took that swing. Spoke a few words. Tipped his cap. Glanced around, eyes repelling tears of current gratitude and nostalgic regret. There he was, legend married to magic: Ted Williams, up there for all the kids who ever were. He is the man who made summer last forever.