THE BOSTON GLOBE

BY MIKE BARNICLE

THROUGH HISTORY WITH STYLE

Jun 9, 1980

Ali had a cold. It had kept him up most of the night and now, just past 7 on Saturday morning, he was sitting in the kitchen of his friend, George Butler, in Marblehead, holding a bottle of pills in the palm of his hand. “One every 12 hours,” he mumbled. “Think I can remember that?” “Want some orange juice, Muhammad?” Butler asked.

“Yeah, orange juice,” Ali answered. “And some ice. Got some ice?”

Ali poured the orange juice over the ice cubes. He placed the pill in his mouth and swallowed after the first sip of the drink. Time and things like common colds are now his enemy.

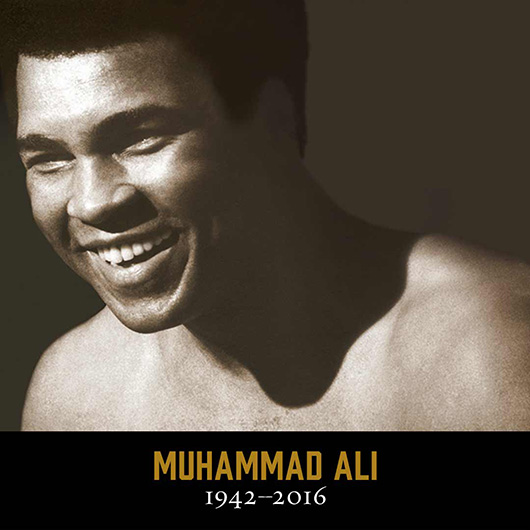

He is 38, this phenomenon of our age. He is, perhaps, the most famous, the most easily recognizable figure in the world. His name – Ali – summons a hundred different emotions whenever and wherever it is mentioned. Three different times he has been heavyweight champion of the world. But he has been much more.

“I don’t have no boss,” Ali was saying. “I don’t have to call no one. I’m a free agent. I do what I wanna do. And my purpose is to teach; to be the first black man that got big. And I’m the biggest thing on earth. I know that. And I’m free.

“When I went to Russia, I went in to see Brezhnev and he got up from his desk and came over and put his arms around me. He says, I been waitin’ to meet you for a long time. All the Russian people know you. And the next day, when I went back to see him, he had his grandchildren there and he says, They know you too.”‘

Ali has marched through history with a grace that knows no time and a style that has conceded nothing to the events around him. He threw away his Olympic gold medal. He changed his name when he found religion. He refused to be drafted during the war in Vietnam. And he kept on fighting and talking; talking and fighting. He has spent 187 nights ducking quick lefts and right hands full of thunder to either defend or get the championship of heavyweights. Now, there are some who say that all of this has taken its toll and Ali suffers from brain damage.

“Could be,” he said, when asked about a doctor’s theory. “Anytime you get knocked out, even for a few seconds, there’s probably brain damage.

“But all that talk’s just people tryin’ to discredit me. Tryin’ to make people think I’m off so they don’t listen to me. But I know that God has got me here for something special. When I was in Russia, I realized there was something divine about my life. A black man in Russia. Imagine that.”

He checked his watch and saw it was almost eight in the morning. Later in the day, Harvard was going to honor him by making Ali an honorary member of the Class of l975. The school had only done that once before, in l930, for Walter Lippmann. “Make sure they mention that,” Ali said.

“Who’s the greatest man you ever met?” Ali was asked as he played with a cup of tea.

“Elijah Muhammad,” he said right away. “He took a whole nation and made them people. People who used to call themselves Negroes, he changed them to callin’ themselves black.

“Why were we called negroes? Is there a country called negro? Chinese, they come from China. Cubans called Cubans cause they come from Cuba. Germans from Germany. French from France. What country’s called Negro. He made us proud. He taught us.

“A black cup of coffee is a strong cup. Black earth is rich earth. Allah made me a world wonder. Allah made me millions. I gave up a lot too. I gave up my title. I fought against the white man’s war in Vietnam. I did this by myself and I was right.

“You say, Anything scare you, Ali?’ What could scare me? I had my jaw broken in a ring. Look at this,” he said, holding up his fist. “You know what would happen to your head if I hit you with this? Vietnam. Gettin’ drafted. Scared of what? What could scare me after all the things I done. Only thing I’m scared of is Allah and his punishment. I’m a spiritual man.

“Superstar don’t mean shit to me. I don’t care about discos. No stuff like that. God made this planet and he created a fighter for God. That’s me.

“And I do what I wanna do. No one could talk like this. That’s my purpose, to talk and to teach. Sure, I played the fool sometimes and they paid me millions to do it.”

Over in the corner of Butler’s kitchen, Howard Bingham, a close friend of Ali and Abdul Rahman, who travels with the champion, had gotten up from the table. Ali’s wife, Veronica, had come downstairs just as three students from Harvard arrived at the house to escort the man into Cambridge.

One of the students was named George Jackson. Jackson grew up in Harlem around Lenox Avenue. His father changes tires and his mother works at the Amsterdam News and the son, being smart and very good at football, just graduated from Harvard on Thursday.

“What’s your name?” Ali asked George Jackson. “George Jackson,” the champion was told.

“Why don’t you use your real name,” Ali wanted to know. “Get a book of history and pick out your pretty name, your name that means something. Now I’m not talkin’ racism. I’m talkin’ truth.”

“Maybe I will,” Jackson said.

“You went to Harvard huh?” Ali wanted to know. “That’s right,” Jackson answered.

“Well you not as dumb as you look then. That’s real good. You gonna make something of yourself. But you oughta use your real name. I bet all your life people was tellin’ you you’d never be nothing.”

“My whole life,” George Jackson said. “Until Thursday.”

“That’s good brother,” said Muhammad Ali. “That’s real good.”