NEW YORK DAILY NEWS

Boston getting used to idea of beating New York following so much heartbreak

Friday, December 28th 2007, 4:00 AM

Mike Barnicle, a newspaper columnist in Boston for 30 years, is a long-suffering sports fan and MSNBC commentator.

How did this happen? Was there a specific date, a single event that erased the burden of history and allowed the weight of municipal inferiority to be lifted from the shoulders of every fan in New England who has been witness to decades of humiliation delivered by New York teams?

Think about it.

Saturday, the Patriots play the Giants at exit 16W. They arrive as undefeated favorites, with three Super Bowl championships in four years, the symbol of how a model NFL franchise is run. A dynasty.

The born-again Celtics humiliated the Knicks and Nets each time they met this fall. Of course, the Little Sisters of the Poor could beat the pathetic Knicks, coached by a delusional paranoid and owned by James (Thanks, Dad) Dolan, a soft, spoiled rich guy who inherited wealth, not wisdom.

That brings us to the main event: Red Sox-Yankees. The Yanks have spent billions but they still wear rings tarnished with age while the Olde Towne Team has two championships in the last four years, ’04 and ’07, turning Back Bay into Hardball Heaven. A minidynasty.

It’s a mind warp.

Manhattan was where Boston’s dreams went to die after being fatally wounded in the Bronx. Time turned the Hub into a pitiable afterthought as commerce moved from New England to New York in the 19th century. And sports turned our teams – fans, too – into one-liner fodder for anyone from The Rockaways to New Rochelle.

You used to be able to identify Sox fans in Yankee Stadium. They sat, slump-shouldered, with the same panicked expectation nervous motorists have looking in the rearview mirror at the 16-wheeler behind them on Interstate 95 near New Haven.

The inevitability of collapse was genetic. Disappointment was delivered with an October postmark by fringe figures named Bucky (Effen) Dent, Mookie Wilson and Aaron Boone.

Then, something happened in October 2004 in the “House of Historical Horrors” called Yankee Stadium. The Red Sox came back from three games down to beat the Bronx Bombers, leading the Daily News to hit the streets with one of the greatest front-page headlines ever: “The Choke’s On Us!”

That was IT, the single moment that pushed the gravedigger into retirement. It took the loser label off the forehead of every Boston fan.

Now, in a bizarre way, we have supplanted New York as the place where champions reside and the home team is hated by others. The Patriots are loathed as much as the old Yankees. The Red Sox are fan favorites who attract big crowds in every town, annoying local ownership. The Celtics are dominating the way they used to when they were despised in the old Boston Garden. We’ll skip hockey because the NHL was ruined because of a long strike and ludicrous expansion.

Ironically, we have seen the enemy (the Yankees from DiMaggio to Jeter and Rivera, the once-glamorous Giants of Gifford, Tittle, Huff, Simms and Parcells, the Knicks with Reed, Bradley and DeBusschere, the Jets with Namath) and, incredibly, we have become them.

We have money, swagger, attitude and standing. We’ve consistently won in baseball and football, and we hit the new year with the best basketball record in the NBA. And, given the short national attention span, nobody cares what happened in the 20th century. Life and sports are about the moment.

Oddly, there are thousands of young people from Waterville, Maine, to Waterbury, Conn., who have no institutional memory of a sporting life once filled with apprehension, even fear, who have never endured the depression that accompanied defeat datelined New York City.

But that was then and this is now: Saturday, the victory parade continues and the dominance of area code 212 is diminished, if not dead.

So, how come I’m still up late at night, worrying the Yankees might sign Johan Santana or the Giants might luck out and beat the Patriots by a field goal with less than a minute left in a game where Tom Brady breaks his leg? Maybe it’s because I’m from Boston and haven’t quite gotten used to living with something called success. But I’m getting there.

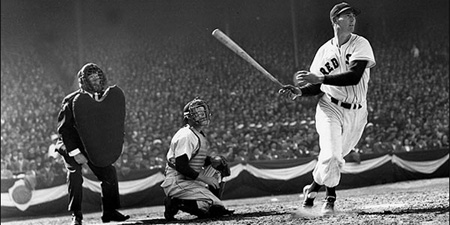

When the old man swung the imaginary bat through the fresh air of a clear, sunlit afternoon, the weight and dust of all the years fell away like marbles toppling off the edge of a three-legged table. Adults clapped. Little kids hung from the rail and sat atop a parent’s shoulder. Some men and women, of a certain age, and with a certain look to them, even cried.

The swing was still smooth as tap water tumbling from a faucet on the hottest of August days. The hips turned perfectly and the huge hitter’s hands rolled right over. The bulk of seven decades didn’t even show through the old man’s sports jacket because all anybody really saw was the number 9.

It seems odd, maybe even sacrilegious, to call him an old man because he lives beyond any calendar. Birthdays do not matter. When you are Ted Williams, nobody adds up the years.

I first saw Ted Williams in 1951. He was part of a pretty good team that could never quite catch the Yankees. When I shut my eyes, his swing at Fenway Park Sunday is the same swing I recall across all the vanished decades.

I first met Ted Williams in 1953. It was the year he returned from Korea. He did not have post-traumatic stress disorder. He did have 13 home runs and, once in awhile, if you waited long enough, you could catch him behind the old Somerset Hotel on Commonwealth Avenue.

In those days, I had very little idea what he might be doing inside the Somerset. Eating there? Living there? Who knew? All I knew was that rumor was the currency of youth and if there was even a whisper that Ted was around the hotel, the stakeout for autographs would begin.

There was no television then. Drugs and guns were unheard of to us, perhaps preposterous myths to older people. The few gangs that did exist were a collection of unemployed guys with duck-tail haircuts and pegged pants. Parents let kids ride trains, buses and trolleys around town with not a second thought given to safety.

We would go the ballpark in clumps. Sometimes we’d go to Braves Field, but more likely it was Fenway because that’s where the greatest hitter in the history of the game lived.

And Fenway became our church. Just as there was a downstairs 8 o’clock children’s Mass each Sunday in the parish, there was mandatory seating at the park: As close as you could get to the sloping left field rail where No. 9 prowled below.

He was then — and is now — larger than life. Unlike so many others — politicians, actors, statesmen, teachers, scientists, war heroes — time has not shrunk or sullied Ted Williams.

And Sunday, when they commemorated the fact that it is 50 summers since he hit .406 (and since Joe DiMaggio hit safely in 56 straight baseball games), you could hear the ballpark talk. Oh yes, ballparks do have voices, and they’re filled with memory and emotion.

I heard it. I think a lot of others did, too. And I’m sure Ted Williams heard it because it nearly caused him to cry in full view of all those strangers.

The ballpark spoke about The Kid from San Diego who hit .400 in that year of lost innocence. We were on the threshold of a war that would change America forever but, back then, baseball was our best seller, a story people bought and talked about every day, a tale told from radios perched on a thousand windowsills as a million men, women and children gathered on stoops and porches, following the action.

Ted Williams is that time. Ted Williams is that country. Other heroes have come and gone. The violence of the brutal years defeated a lot of dreams, but Ted Williams remains. Still looking like . . . well, Ted Williams.

Why has he survived? Simple: He could do whatever it was that needed to be done. You need a guy to hit .388 with 38 home runs? No problem. You need a man to sit in the cockpit of a fighter plane and protect democracy? You need someone to make sure John Glenn doesn’t get killed in Korea before he flies into outer space. Are you looking for a straight-talking, truth-telling, uncomplicated, no bee-essing, get-it-done, old fashioned, can-do, American kind of guy. Meet No. 9.

Baseball is a funny thing. It’s bigger than just a game. It has all these memories and stories attached to it, which makes it truly unique. Who tells football or basketball stories? What kid really has an indelible hockey memory?

Sunday, you could see — really see — through the fog of those long-gone summers. And you could hear — absolutely hear — the ballpark talk when Ted Williams stepped to the microphone, The Kid come home.

Then he took that swing. Spoke a few words. Tipped his cap. Glanced around, eyes repelling tears of current gratitude and nostalgic regret. There he was, legend married to magic: Ted Williams, up there for all the kids who ever were. He is the man who made summer last forever.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction or distribution is prohibited without permission.

Abstract (Document Summary)

I first saw [Ted Williams] in 1951. He was part of a pretty good team that could never quite catch the Yankees. When I shut my eyes, his swing at Fenway Park Sunday is the same swing I recall across all the vanished decades.

Ted Williams is that time. Ted Williams is that country. Other heroes have come and gone. The violence of the brutal years defeated a lot of dreams, but Ted Williams remains. Still looking like . . . well, Ted Williams.

Then he took that swing. Spoke a few words. Tipped his cap. Glanced around, eyes repelling tears of current gratitude and nostalgic regret. There he was, legend married to magic: Ted Williams, up there for all the kids who ever were. He is the man who made summer last forever.

BOSTON GLOBE

April 13, 1986

Baseball is a game of memory, and it returns tomorrow to a place where grass has not yet given way to a carpet. It comes home to a green haven filled with reminders of both heartbreak and happiness, a ballyard called Fenway Park where the cargo of past athletic time refuses to yield to sports’ current themes of greed and arrogance.

Baseball is a mood, a suggestion of sunshine and subway stops that all seemed to lead to Section 16. Once, it was truly the city game, truly America’s pastime and certainly the one sport that bound generations together. Fathers sat with sons and daughters and shared the mellow remembrances of other Opening Days played in earlier, easier afternoons before night stole the game. Then, the shadows of history and reality could be shuffled effortlessly around like so many boxes filled with relics of youth on moving day.

And the stories never had to be anchored in fact. As the calendar moved forward, hits, runs and errors became less important. Mood and memory prevailed.

There, right over there behind the dugout, is where Teddy Ballgame’s bat landed after he threw it in disgust and it hit Joe Cronin’s housekeeper. And do you see the first-base coach’s box? That’s where Dick Stuart bent down to pick up a hot dog wrapper and got a standing ovation because it was the only thing he ever picked out of the dirt with his glove.

The park still rumbles with the aftershock of visions long since gone: Shut your eyes and Joe DiMaggio is still making his last appearance in Fenway. Jimmy Piersall is still squirting home plate with a water pistol. Tony C. is down in the dust, and the crowd’s deathly silence still makes a noise in your mind.

Don Buddin can reappear at any moment. Within your own personal game, Rudy Minarcin, Matt Batts, Jim Mahoney, George Kell, Billy Klaus, Jerry Adair, Clyde “The Clutch” Vollmer, Rip Repulski, Mickey McDermott and Gene Stephens can be the components of your bench.

Baseball is part of history’s menu. It is filled with small slices of youth, adolescence and adulthood, and anybody can order a la carte.

Baseball is not the present ugliness, where rich men called players argue with richer men who are owners over decimal points and deferrred payments. Baseball is not agents or options or no-trade clauses.

It is not whining athletes who play only for themselves and their bank accounts. It is not the corporate set interested in owning franchises merely because of the benefits accrued under the tax code.

Baseball is a passport to the country of the young. It is Willie Mays chasing down Vic Wertz’s long fly ball in the Polo Grounds. It is Lou Gehrig considering himself the luckiest man on the face of the earth. It is the Brothers DiMaggio. It is Jackie Robinson and Number 9. It is the magic of Koufax, the consistency of Seaver, the toughness of Catfish Hunter and the grace of Jim Palmer.

It is a double play turned over in a cloud of dust and metal spikes. It is Captain Carl fouling off the last pitch of a play-off game that started on a splendid October afternoon and ended in a long, cold winter as soon as the ball was firmly nestled in Graig Nettles’ glove.

And Opening Day is a time for all those trophies of the mind to be taken out and dusted off. Opening Day, especially the home opener, means the newspapers once again provide box scores, and life contains one sure sanctuary from the grimness and terror of daily headlines.

It does not matter that this present collection of 24 men in a Red Sox uniform are not truly a team. It does not matter that they lack chemistry, consistency, speed and a fundamental ability to hit the cut-off man or get a runner in from second base without depending on the thunder of a 34-ounce Louisville Slugger.

The moaning of crybabies and players who perform with salary arbitration first in their minds can not drown out the collective noise of generations of fans who love the sport while despising its present state. After all, it is still the best game ever played by men anywhere.

What other sport has planted itself so firmly in the nation’s psyche? What other sport draws people to the radio — one more relic of yesterday — to sit and listen to the long innings of slow summer nights? What other sport plays itself out in front of a fan as clearly as baseball?

You can see who made the error. You can see who got the hit. You can marvel at the clothesline throw the right fielder makes to the catcher, and watch the runner dueling with the pitcher for a slight lead off first.

Football is as predictable as roller derby and as anonymous as a gang fight. Basketball is a spectacle of tall men on a court in a contest where only the last five minutes seem to count. Hockey is brawling on skates. And all of them are played at the absolute mercy of the clock.

But baseball is timeless, and so, too, are its memories. Like the players themselves, scattered about the diamond in position, the memories of baseball can be isolated and called up on a mental Instant-Replay whenever the mood or moment summons: Do it today. Do it tomorrow. Do it 10 years from now, and all the detail, drama, symmetry and scores will tumble out.

Each new start to baseball’s timeless seasons, each Opening Day, provide a fresh chapter in life. The first pitch, the first hit, the first double play or home run become another page in a volume kept by the generations.

So, years from now, long after the disappointment of having no strikeout pitcher in 1986’s bullpen has faded, when all the home runs and dents in The Wall have been rendered meaningless by a lack of base-running ability and an incredibly poor defense, the sad failures of this year’s edition of our Red Sox will not matter.

Boston Globe

September 30, 1983

Once, it was a simple game played on grass under the sun and fans deceived themselves into thinking that men played it only for fun. Over the years, the night took it from warm afternoons and there are green carpets now instead of lush lawns and the explosion of dollars has turned the music of the sport into the sound of an adding machine.

Kids no longer pose in playground shadows pretending to be DiMaggio, Mays or Mantle. The ballet involved in chasing long fly balls or the visual poetry of a double play is still there, but free agency and labor disputes have resulted in loyalty that has turned to rust.

Lawyers and owners speak in Wall Street tones; players mutter in some dead language that always has a clause for cash; and all three parties are part of a deceit that has robbed the game of its magic and the fans of a piece of their youth.

Yet through it all, across all the years, you can always find a handful of athletes who act and perform as if they are the custodians of the game’s reputation, as if their every time at bat is going to help restore a piece of the dream that every child once held in his heart whenever baseball was played.

Carl Yastrzemski is such a man.

He never had the power of a Jackson or a Schmidt. He never had the speed of a Clemente. He does not have the size or strength of someone like Winfield or Rice.

He approached the game the way a carpenter frames a house. His foundation was desire; the walls were made of intensity; the roof was nailed down with heart.

His career has stretched across the terms of six presidents, a couple of mayors and two decades that have changed the face of this country forever. There are people just one year out of college whose entire memory of the Red Sox is book-ended by the name Yastrzemski.

He played on some awful teams, some good ones and, perhaps, one great one. He was stacked in batting orders with players who were pathetic and a few others who had better natural ability and physical gifts than No. 8 did.

Through it all, the first- and last-place finishes, the embarrassment and the applause, it was always Carl Yastrzemski’s pride that bound those teams together and carried them through the long season. From March to October, he ran everything out.

He was “The Captain,” but his speeches were given in the batter’s box and out along the cinder track in left field. He was an all-star but the glitter in his game came from his consistency. He was a steady light in the sky, not some shooting star that faded in a haze of adhesive tape, whirlpools and excuses.

His talent was always disguised within a body better suited for a journeyman infielder. And there were years when he was hurt nearly all the time and the numbers from those seasons libel his career when looked at separately.

But he played. He altered his stance or favored his back. He limped a bit and took a little off the throw in to the cutoff man but, always, he played.

And all the games across all the years do not encompass one third the effort that Carl Yastrzemski poured into his sport. Box scores don’t show callouses picked up from hours in a batting cage and statistical totals don’t compute the sweat, pain and sacrifice of a life devoted to a game.

In September of l967, he became a legend. No man has ever had a month, a season, like Yastrzemski did sixteen summers ago. Day in and day out, he lugged a marginal collection of baseball players toward the dream of a first- place finish.

In the fall of l975, he was an aging left fielder on a team of considerable talent. But it was Yastrzemski who took a ball off the left field wall, turned and fired to throw out Reggie Jackson, who had thought he could take second on an old man’s arm, and when the umpire called him out, the Oakland A’s died right there in the copper-colored dust of the infield.

By l978, there was a touch of gray at his temples and the lines around his eyes were not from laughing. And it is in a scene from a crisp, clear October afternoon of that year that Carl Yastrzemski will live forever in my mind.

His Red Sox had bled themselves into a tie for first place with the Yankees of New York. Now it was the ninth inning of a playoff game and 32,295 fans stood in silence for the duel: “The Captain” against “The Goose.”

They say the ball finally came down in Graig Nettles’ glove. They say there was a final score, and that the Yankees won. But they are wrong because legends live forever and there are dreams that never die.

In places beyond New England, there are people who claim that “The Captain” never played on a team that won a World Series. Yet on that autumn day, and on every day he wore the uniform, Carl Yastrzemski, No. 8, was always a world champion.