With husband Bob, Myra Kraft attended many fund-raisers, smiling and greeting donors. (1997 File/The Boston Globe) |

The 26-year-old aid worker taken by ISIS left Arizona to help a people suffering through civil war. Now, her courage should remind us of all the good we’re still capable of.

She looks quite happy in the pictures displayed last week in most American newspapers and on TV. She is smiling, the smile speaking for itself, saying “I’m doing what I’ve always wanted to do.”

Her name is Kayla Mueller. She is 26 years old, a resident of two places: Prescott, Arizona and the world. And until last week not that many people knew that she had been kidnapped off a street in Aleppo, Syria and has been held hostage by ISIS since August 2013.

Her name became truly famous only when the media wing of the crazed, criminal and murderous cult that is ISIS claimed she had been killed in a bombing raid conducted by the Jordanian Air Force. Jordan and its King flexed their military muscle after a young Jordanian pilot, another hostage held by ISIS, had been burned alive in a cage.

Today, the civilized world does not know whether she is dead or alive. That, due to the fact that a small tribe of demented killers—ISIS—has no moral compass or conscience and could still be holding her for a more macabre purpose.

What we do know however is this: Kayla Mueller is us. She is what the United States truly is, or used to be, even though that definition of who we are has been diminished across the last decade or so.

Kayla Mueller was working along the Turkish-Syrian border with a group from Doctors Without Borders. She was in the middle of one of the largest, most dangerous refugee problems in the world in a place where hundreds of thousands have been sentenced to a life wandering through a wasteland of a civil war that has destroyed Syria.

She wasn’t there for a big salary, media attention or the pursuit of celebrity. Clearly, what she was doing was who she was. And she was not a novice when it came to lending herself to those in need.

According to reports in her hometown newspaper she had volunteered at a women’s homeless shelter and a HIV-AIDS clinic in Prescott. Before she arrived in Turkey, she had been to India and Israel helping in refugee settlements there. She was learning Arabic to better communicate with those crushed and on the run from violence.

Then she was gone. On the morning that she was supposed to catch a bus in Aleppo for the return to Turkey she became one of “the disappeared”. And for all these months, from the summer of 2013 to last week, her parents along with a few family friends and the United States government wondered, worried and worked at gaining her release; that, every hour of every day.

But this week brings us back to a hideous reality of our present culture. The name—Kayla Mueller—is no longer the big news lede. Her story has dropped off most front pages and the top of the network news.

We’ve moved along. Twitter’s attention span can’t wait for Kayla. After all, we have Brian Williams and Bruce Jenner to focus on, a major obsession. We have a new poll out of New Hampshire showing Jeb Bush with a slight lead in that state’s Republican presidential primary, an election one year away. Plus, we’re still sorting through the after-affects of what various and absurd candidates have said about vaccinations and why the President mentioned The Crusades at the National Prayer Breakfast. Oh, and don’t forget the Grammy Awards and what they mean to the future of America.

Prescott, Arizona has a population of 40,000. In the summer of 2013, only weeks before Kayla Mueller vanished in Syria, the town was brought to its knees when 19 local men, firefighters, died combating a wild fire in the nearby mountains. The memory of that loss remains as vivid as the clear blue sky that dominates most Arizona days.

Now the nightmare continues with the agonizing mystery surrounding one young woman who went out to the wider world armed only with the best of American intentions: To help those who need help the most.

https://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/02/08/kayla-mueller-the-best-of-america.html

Lost in the right/left debate over the new Clint Eastwood film is how few Americans fought this century’s wars, and how the suffering of their families has often gone unnoticed.

During the course of any normal day I usually pay more attention to assembling a grocery list than I do to reading movie reviews, although there are a more than a few film critics who bring huge insight to their work. A.O. Scott of the Times, Joe Morgenstern of the Wall Street Journal and Ty Burr of the Boston Globe are always in my lineup.

But for the past several days it’s been interesting to scan the landscape of different views surrounding American Sniper, the Clint Eastwood-Bradley Cooper film about the life of Chris Kyle, a Navy SEAL who grew up in Texas and served his country – that’s us as in the United States of America—during four tours in Iraq, a war that has managed to mangle two nations, ours and theirs.

Like nearly everything else—a ball game, a rock concert, a political debate—anyone who buys a ticket or takes the time to watch instantly becomes a critic. And today, with twitter and texting and all the other tools we have literally at our fingertips, a debate quickly turns into a cyber-space brawl.

People on the left go back and forth with those on the right about the movie’s merits. Is it pro-war? Is it anti-war? And while a platoon of professional essayists, film aficionados and all around ‘I’m smarter-than-you’ folks attack one another’s opinions, there seem to be a couple items that have been forgotten along the side of the long road we’ve traveled for 15 years—15 years!—in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The most obvious is the lack of attention paid to the fact that only about one percent of our population has borne the weight of war. Then there are the families left behind while those fighting are deployed multiple times to both theaters—Iraq and Afghanistan—breaking the military and too often breaking those who sit state-side, worrying, waiting, while 99% of everyone around them dances through the day without any real prospect of danger or death knocking on their door.

In a lot of the reviews of American Sniper that obvious fact is not mentioned. Instead there is amazement at how popular the movie has been since it was released nation-wide a week and half ago, wracking up record box-office returns.

But a strong case can be made that Eastwood and Cooper have produced one of the few films that go beyond an attempt to put the reality of war on a big screen. That is an impossible venture. Nothing can ever come close to the actual violence, fear, noise, clamor, courage, carnage, and the mind altering, lingering, lasting damage done by war to those charged with fighting it.

Yet there is a scene in Sniper that gets to what veterans of wars carry forever and what that burden has meant to all those who wore the uniform from Cemetery Ridge, Somme, The Bulge, Iwo Jima, Chosin Reservoir, Hue City, Mosul, Helmand Province and hundreds of other spots scarred by war: the scene in which Bradley Cooper and his son are in a garage waiting to pick up their car.

The boy is approached by a young Marine who lost his leg in Fallujah. He tells Chris Kyle’s child that his dad is a true hero who saved his life and the lives of other Marines through the devastating skill of his marksmanship, a sniper watching over the constant danger on the urban battlefield below.

Cooper barely moves, hardly utters a line. Instead, the toll of who he is and what he has done and what he must surely never want his little boy to endure is in his eyes and on his face, a portrait of inner pain he wrestles with daily.

A friend of mine who worked on American Sniper for months and attended several screenings in places as different as Dallas, Los Angeles, New York City and Washington D.C. had an interesting observation that mutes some of the ideological ‘wars’ that have consumed multiple critics conducting operations from the safety of their laptops and iPhones.

It revolved around the scene where Chris Kyle sights, shoots and kills the major-league caliber Iraqi sniper from a distance of more than a mile away. In a sand storm.

At a screening in L.A. and New York, the crowd cheered. In Dallas there was no cheering. And when the film was screened at one site in Washington there was only a heavy silence.

Where was that location? Walter Reed National Medical Center, where the wounded, the limbless, the brain damaged are treated for injuries that linger forever and are largely forgotten by a country and a culture where more attention is paid to deflated footballs than the needs and cost of caring for men and women who fought in Iraq and Afghanistan.

American Sniper is a movie. War is a grim reality and with us still.

https://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/01/25/what-american-sniper-gets-right.html

Pope Francis demoted the reactionary Burke, but that hasn’t stopped him popping off about how the Church panders to radical feminism.

Cardinal Raymond Burke is a 66-year-old guy who lives in Rome, dresses like Queen Elizabeth, and talks like someone who majored in misogyny at some bogus, backwoods, Bible-banging tent school. Until Pope Francis stripped him of the powerful Vatican post Pope Benedict had handed him, Burke behaved like the Catholic Church’s version of Ted Cruz, operating with an ego and an attitude that proclaimed him to always be right on matters of doctrine and dogma.

Burke’s new post makes him the equivalent of a head waiter at the annual Knights of Malta Communion breakfast, but the demotion has only emboldened him. A few days ago the former archbishop of St. Louis was interviewed by some pamphlet geared to restoring guy-talk in Catholicism, and Burke did not disappoint.

“Unfortunately, the radical feminist movement strongly influenced the Church, leading the Church to constantly address women’s issues at the expense of addressing critical issues important to men,” Burke told the correspondent from a pamphlet called (get this) The New Emangelization.

“Sadly,” he pointed out, “the Church has not effectively reacted to these destructive cultural forces; instead the Church has become too influenced by radical feminism and has largely ignored the serious needs of men.”

As I read Burke’s manifesto on his desire for more arm-wrestling, towel-snapping, locker-room guys to play larger roles in Catholicism, a couple of thoughts went round and round in the carousel within my noggin: those attending mass today in too many American parishes resemble people sitting around the day-room of an assisted living facility. God love them but they are old, committed, and slowly disappearing.

The church in the United States is not exactly a growth industry. Parishes are being closed or merged. There are too few priests and not exactly a lot of people lining up for a vocation that requires and insists on celibacy.

The second, almost immediate thought was of a woman I knew quite well whose husband died young, leaving her with a few children and an absence of both money and employment in a struggling New England factory town where the paper mills and textile plants were heading south at a pace that soon left Main Street looking like abandoned property.

She buried her husband on a bitter cold December morning two days before Christmas during John F. Kennedy’s first year in the White House. She could curse in Gaelic and pray in Latin.

She had no job, but quickly, within weeks of her husband’s death, she began working at the rectory of the large Irish parish where the church steeple was just about the highest point in town, built by other immigrants in the 19th century as a bold statement announcing their arrival. She did the priest’s laundry, washed and ironed altar linens and vestments, and prepared lunch and supper for four or five priests, two of them veterans of World War II.

She took home less than $60 a week. She went back to school, enrolling in one of what was then called a “teacher’s college” in the old Massachusetts community college system.

After she got her diploma she began teaching fourth and fifth grade at the parish parochial school, where she remained for three decades. She went to mass every day of the week and prayed nearly as much as she breathed. When her youngest boy was in Vietnam she became a daily communicant, a routine that continued after his war service ended.

Her faith was stronger than steel. Her belief that God was all-knowing and forgiving was unshakeable. She was in the forgiveness business and had a deep understanding of human frailty, an insight that never left her until she died at 93.

I called her “my mother the nun.”

So when I read Raymond Burke clowning it up with his bogus beliefs that the Catholic Church has lost a few steps because of the absence of “manly men,” I could hear Mom muttering, “pol’thoin” (asshole) to describe him. That description would have been applied for many reasons but the biggest would be the most obvious: Burke is a guy whose most firm belief is in himself and his own pronouncements.

The cost of his gilded, ornate vestments could feed a family of four across a decade. He has exhausted himself and more than a few who have had to listen to him trying to ban pro-choice politicians from receiving communion. He has attacked St. Louis University basketball coach Rick Majerus for attending a Hillary Clinton rally and tried to prevent Sheryl Crow from giving a concert to raise money for a Catholic hospital.

Last year, as Pope Francis began turning the lights back on within a church that has seen legions depart simply because so many in the clergy said so little about the criminality and obstruction of justice surrounding the reality of sexual abusers wearing roman collars, Burke said, “There is a strong sense that the Church is like a ship without a rudder.”

Raymond Burke: Member of the College of Cardinals and captain of a ship of fools.

It all started back in November 1979. We couldn’t do much about extremism then, and it seems we can do even less now.

By early November 1979, America was exhausted. The ever-shrinking president, Jimmy Carter, had been attacked by a rabbit while running and that July had taken to the television to tell us the country was suffering from a breakdown, that a malaise had seized the land.

Interest rates looked like major league batting averages. Long lines formed at gas stations because Saudi Arabia and OPEC decided to yank the chain of “The Great Satan” by slowing oil production and exports. A meltdown at the Three Mile Island nuclear facility had threatened to turn half of Pennsylvania into a green night light.

Then, on Nov. 4, 1979, the forebears of the three murderers killed last week in Paris by police gathered in a mob outside the American embassy in Tehran, stormed the building, captured nearly all inside and held 42 citizens of the United States hostage for 444 days.

Both ABC News’ Nightline with Ted Koppel and our modern age of terror were born. A lot has happened between then and now: In October 1983, 220 Marines were killed in Beirut by suicide bombers claiming to represent some outfit they called Islamic Jihad, with more Marines dying that day than had been killed in the first week of the Tet Offensive in February 1968. Embassies in Africa were attacked over the next decade. In October 2000, the USS Cole was blown up while at port in Yemen, killing 17 U.S. sailors. Through all of it, threaded between each attack, was the whispered name of Osama bin Laden. Then came September 11.

Now we have the latest assault on civilization: Paris, where the casualty list is filled with the innocent who, once again, died simply because they went to work. Cartoonists, writers, police officers, shoppers, caught and killed by three men driven insane by their own inadequacies.

“These guys were barking mad,” former Sen. Bob Kerrey said the other day. “But whenever something like this happens we always hear and read about the roots of youth disenfranchisement in the Middle East and there is a lot of that, too much of it. Too much unemployment and hopelessness. No doubt about it.

“But guess what: There is a lot of youth disenfranchisement in Latin America and right here in the United States and they’re not walking around killing people in the name of their religion.”

Bob Kerrey served two terms in the United States Senate. He was a member of the Senate Intelligence Committee and, later, the 9/11 Commission.

“The fact is that Muslim leaders are going to have to face up to the violence that is smearing and staining their religion,” Kerrey was saying. “In too many parts of the world, religious leaders are standing in pulpits on Friday night suggesting that violence is OK.

“And what they’ve done and what they continue to do is give rise and reason to a whole new army. It’s not like it used to be in ‘the old world’ as we once knew it. They don’t wear uniforms in their army anymore. The war is all up there in their head, and it’s going to take a long time for us to combat that.

“I don’t know if the Muslim leadership can face it but that’s the reality of their task. They have to address the cancer within, publicly and loudly.”

Over the past few days, the streets of Paris and many other cities around the world have been filled with people standing in outrage over the slaughter that occurred in the offices of the French magazine Charlie Hebdo. That is where the now-dead Kouachi brothers walked in with the nonchalance of mailmen and opened fire on the staff because of cartoons that had appeared in the magazine’s pages. The thought of turning the page or not buying the book was apparently too much for their diseased minds to grasp.

So today the phrases “Je suis Charlie” and “I am Charlie” ring the globe. Yet it has somewhat of a hollow echo because in some quarters, especially in America, the threat to speech, no matter how offensive and the cartoons in question were clearly on the border of outrageous, is bold and quite present. Former New York City Police Commissioner Ray Kelly was recently booed from the stage and prevented from speaking at Brown University, where he was going to talk about policing and protecting our largest city; “Je suis Ray Kelly?”

This war on terror that now engulfs the world, this clash of cultures and civilizations, this riot of religious zealotry that has claimed far too many while unfairly maligning too many of its members, has been a weight we’ve carried and conducted for decades. Drones and SEAL Team Six and all the battalions of stable nations combined can only combat it to a draw. No military weapon in the arsenal is capable of killing a disease, a warped ideology wrapped and camouflaged within a religion hijacked and used by stone-cold, mentally ill killers who arrive with gun, bomb, and suicide vest proclaiming a false cause.

https://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/01/11/a-war-that-will-not-end.html

His ambition for himself wasn’t great enough (he should have run!), but his ambition for America was as noble as a politician’s could be.

I looked up to Mario Cuomo the first time I ever met him. He was standing in the batter’s box at Joe DiMaggio Park in the North Beach neighborhood of San Francisco on the July morning of the day he was scheduled to deliver the keynote address at the 1984 Democratic National Convention later that evening.

It was a softball game that had been assembled by Herb Caen, the iconic San Francisco Chronicle columnist, and Tim Russert had suggested to Cuomo that he ought to drop by for an at-bat to show a pack of hung-over newspaper guys he still had a little game in him. Caen was pitching and I was crouched behind the dish, catching. Marty Nolan, Dave Nyhan, Curtis Wilkie, Tom Oliphant, and myself, all from the Boston Globe, were in the field as the Governor of New York took off his suit jacket, handed it to Russert, rolled up his sleeves and grabbed a bat in a manner that indicated he had done the same thing many times before.

I still remember the first words I ever spoke to him too: “Hey Governor, you’re wearing cop’s shoes,” as he stood there, a pair of black cordovans on his feet. I don’t recall his reply but I do remember he laughed while he took a couple practice cuts, his thick hands gripping the bat lightly.

Caen threw. Cuomo swung. And the ball came off the bat like a laser, streaking over second base on a line, landing on the asphalt outfield, splitting the fielders and rolling all the way to a far concrete wall.

Cuomo never moved. Simply dropped the bat, retrieved his jacket, watched the ball keep rolling, smiled and said, “ Thanks for taking it easy on me Herb.”

Now, he’s gone and his words are being recalled and repeated in the many tributes being written and recorded as if his speeches contained the singular substance of the man. But Mario Cuomo was so much more than well-crafted phrases. He was a living, quite visible and vocal reminder of the soul, the heart, the strong spirit behind the greatest story ever told: the American dream.

One year after he effortlessly lined that shot into left center field at Joe DiMaggio Park, he was in Cambridge where he gave the Class Day address at Harvard graduation ceremonies. And what he said on June 5, 1985 fits the mood of the moment three decades later.

“America was born in outrageous ambition, so bold as to be improbable. The deprived, the oppressed, the powerless from all over the globe came here with little more than the desire to realize themselves. They carved a refuge out of the wilderness and then, in 200 years, built it into the most powerful nation on earth. A place that has multiplied success for generation after generation of its children. I’m one of those children.

“…We built an America of great expectations…We struggled to provide those things for everyone. For brown, black, and white. For every state and every region and every town. We, the people, created a government that enabled us to do together, as a country, what no one of us could do so well – or at all – by ourselves…We reached out constantly to include the excluded…We did it hesitantly at times – sometimes reluctantly – but gradually – inexorably – we always moved toward the light.”

Today, many feel as if that ‘light” is no longer a 100-watt bulb but, instead, a cost-saving 50-watt where more than a few of us simply have to live in shadows. But that was never Mario Cuomo. He was a dreamer, an idealist, grounded in the reality he observed around him. A practical man who refused to run from the dreams that always drove him. A soldier in the service of ideals and aspirations that formed his core. A governor, a politician, a national figure? Sure, all of those and more but something else, something bigger, was his constant moral compass and focal point of any conversation I ever had with him: His family, your family, the idea that almost anything – any trouble, any ill, any hope – could be explained or outlined in the framework of a neighborhood, global idealism defined as if the world were one big block.

At times, Mario Cuomo seemed to have the humility of a Jesuit and the goals of an emperor. He had a big-picture view of life and politics that was framed forever by beliefs instilled in him by his parents, his faith and his unswerving loyalty and love for his wife, his daughters, and his two boys, whom he spoke of as if they were queens and kings. He sought and received any parent’s ultimate reward: the success and happiness of his own children.

So now it is a warm June day in 1992. Tim Russert and I are driving back to the Albany airport after taking our kids to the baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. We call the governor to see if he’s got time for a visit.

Our kids were seven and eight years old and were without a clue that only months before a whole political party had clamored for Cuomo to run for president. The governor’s office looked larger than a football field to the little boys, but when they walked in, it wasn’t Governor Mario Cuomo who was there to greet them. Instead, it was Mario Cuomo, father, baseball guy, who was there for them with his smile, his laughter, his warmth and a flood of baseball trivia questions.

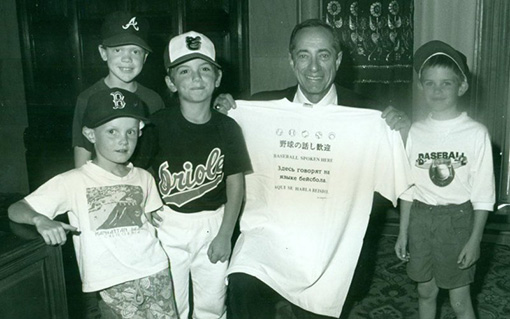

One of the kids had a ball in his hand, and Cuomo took it and tossed it back and forth to an eight year old. The kids had a gift for him too, a tee shirt with ‘Baseball Spoken Here’ stenciled across the front. And he had a gift for them: the lasting memory of time spent with a man who was bigger than the big dreams he had for those little children.

Across all the years, whenever I’d bump into him in New York City or speak with him on the phone, he’d always inquire about those boys, where were they in school, how were they doing in life. Whatever frustrations or disappointments he felt about politics never surfaced. Only an optimism rooted in his own sense of self and the route that had taken him from a home where his parents did not speak English to a position on our national landscape where his own voice and his own words could make people believe that the dream he lived could be theirs too, if only we listened and paid attention to who and what we really are as a country.

In July 2004, Cuomo was interviewed by his old pal, Tim Russert, for Tim’s CNBC show. Here is a snapshot of who Mario Cuomo was:

Tim Russert: Do you wish you had run for president someday?

Mario Cuomo: No

Russert: Never?

Cuomo: No. I don’t think I was good enough to be a president and you – you know, I – I really – I remember an editor – I won’t share his name but you can guess who it is. He was at The Times, and he says, ‘I don’t think you got the fire in the belly.’ I said, ‘Show me a politician with fire in the belly and I’ll spritz his mouth with seltzer.’ I said, ‘Who – who wants fire in their belly? That’s ego.’ I – I never felt that way about the presidency, as you – as you probably know. I – to – to say to yourself, Tim, that you’re better than all the other people out there who are available to lead this country, and therefore much of the world, that takes a little more self confidence than I ever had, I think. “

Mario Cuomo wasn’t wrong about too many things in his life. But he was wrong right there.

https://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/01/04/mario-cuomo-always-moving-us-toward-the-light.html

Will those who protested Eric Garner’s death rush to the side of Rafael Ramos’ two sons, or Wenjian Liu’s widow, married only two months?

Now, in New York City, where tourists are often surprised by the relative sense of safety on streets and subways, it is Officer Rafael Ramos, 40 years old, and his partner, Wenjian Liu, 32, who cannot breathe. They are dead, executed for the clothing they wore to work on a Saturday in December, four days before Christmas.

Liu, Asian, and Ramos, Hispanic, were shot to death by an assassin named Ismaaiyl Brinsley, 28, African-American, who began his day miles south of Brooklyn in Baltimore, a gun in his hand and a diseased dream in his mind of killing police officers, posting his goal quite publicly on Instagram, writing “They take one of ours, let’s take 2 of theirs.” His success later in the afternoon has staggered a nation and sent two families reeling from heartache that never diminishes.

By now the details are grotesquely familiar: Brinsley, career criminal, arrived in Brooklyn with, what else, a semi-automatic handgun and target opportunity, Liu and Ramos, seated in a patrol car parked on a borough boulevard in the middle of the day. In the time it takes you to snap your fingers three times, two New York City police officers were gone, the cruiser splattered with blood, the city they represent quite shaken, and the department they belong to outraged at what it feels is a distinct lack of either support or understanding from a recently elected mayor, Bill de Blasio.

For months, nearly every police department in the country has been alert to tension after the July death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, shot dead by a police officer who apparently had all the training of a mall cop, left shot and dying for hours on a street like a dead dog. There was a grand jury and there was no indictment issued. Riots ensued. Fire lit the Missouri nights.

Weeks before Brown was killed, Eric Garner died on a Staten Island sidewalk after being grabbed around the neck and wrestled to the ground by a squad of New York cops, the entire scene captured on cellphone video. Garner’s “crime” was selling cigarettes by the handful. Again, a grand jury was convened. And again no indictment.

The weight of both decisions ignited protests across the land. Each day and almost every night people took to the streets in largely peaceful demonstrations decrying the apparent indifference of a judicial system that seemed to ignore eyesight along with evidence.

In New York the marches could have been used as training films for other police departments. The cops were restrained and respectful. The men and women wearing the uniform were more diverse than the crowds they protected as they helped them proceed along streets, displaying their grievances. All of it, with only a few exceptions, was peaceful.

Simmering beneath the surface though was the clear divide between a patrol force recognized as the finest in the country, if not the world, and a mayor, de Blasio, who has by word and action divided himself from the one municipal department that provides citizens with something necessary to keep a city breathing and moving forward daily: a sense of security.

Most cops are not looking for understanding. They work in a world filled with a sense—real or imagined—of danger lurking around each corner and every hallway. Most cops are merely looking for respect.

Unlike other professions—doctor, lawyer, teacher, journalist, sales clerk, stock broker—when a cop makes a bad mistake it could mean someone is dead. They take home mental baggage unlike anything carried in almost every other job.

Now, two of them are dead. “Assassinated,” in the words of New York City Police Commissioner Bill Bratton.

So who will hit the streets to galvanize support and express rage over the execution of two young men killed because of who they were and what they did for work? How many of those who protested will rush to the side of Rafael Ramos’ two sons? How many will be there for the young widow of Wenjian Liu, married only two months?

Saturday, when Ramos and Liu began their tour of duty, neither man expected it to end in their death. They were where they were because they stood, like so many others in uniform, as a blue line between order taken for granted and the potential disorder always there.

Both men, homicide victims like Brown and Garner, were not unlike the thousands of others sworn to protect and serve all of us, no matter our race or religion. They knew each day brings danger. They knew they might see things that will disturb them, but could not deter them from their duty. And they knew that only a few truly understand the world they lived and worked in, other cops who wear the same clothing that cause them to become targets for any deranged individual with a gun in his hand, demons in his head, darkness in his heart.

Now, during Christmas week, many of the politicians and phony posers who have labeled all cops as dangers because of the behavior of a few, will pay their respects to two who died in Brooklyn, ambushed, never even drawing their service revolvers. They will do this without realizing the tragic irony involved in paying respects to the police who rarely ask much more than exactly that: respect for what they are asked to do and what they represent to a society seeking order and peace.

A new movie and a visit to the 9/11 memorial remind us what’s at stake when America doesn’t live up to its ideals.

On a Saturday buffeted by a cold December wind, thousands strolled with somber step through one of New York City’s two historic cathedrals. Outside, hundreds more waited patiently in a long line to enter; once inside, their voices were muted and the very young, holding a parent’s hand, would be told about a brilliant, cloudless September morning when America changed forever.

This was the National September 11 Memorial Museum over the weekend, a place that documents our vulnerability as well as the nobility of so many among the dead. It is miles from St. Patrick’s, and Saturday the distance between the two sites was quite congested, with about 25,000 marching along Sixth Avenue in orderly protest over the recent deaths of Eric Garner and Michael Brown, two events that have also altered the country.

This was also the week when the United States Senate Intelligence Committee released an indictment that declared beyond doubt that the CIA tortured some captured during the war that began on that horrific September day 14 years ago. In all three locations—the museum, the Fifth Avenue cathedral, the streets and sidewalks of the world’s most famous city—prayers for the souls of the departed resonated.

Surrounding all of these places and hundreds of others you could see the season’s lights brightening store windows and you could see the mobs of tourists pushing against each other to take pictures of the enormous tree standing in splendor above the ice rink at Rockefeller Center. Here, in the middle of the warped excess that is the heart of Fifth Avenue windows, there seemed to be no sadness and little memory of the defining event of our century.

At the memorial museum, it is the eyes of those taken by terror that speak softly, silently, to visitors. Portraits of most of the 2,977 victims on September 11 are displayed on the walls. They died for simply going to work that morning, killed by religious fanatics, homicide victims all.

The eyes of people like Thomas Patrick Cullen III, firefighter, Squad 41, husband, father, 31 years old. The eyes of Welles Crowther, the man in the red bandana, Boston College graduate, equities trader at Sandler O’Neill. The eyes of Betty Ong, a flight attendant on American Airlines Flight 11, dead at 45, and the eyes of Amy Sweeney, another flight attendant on Flight 11, wife, mother of two, gone at 35. And so many more.

We have been at war for a long time and the fight promises to continue well into the future. We are a huge, complex, diverse country still offering freedom, opportunity and hope. Nobody is knocking on the door of places like China, Egypt, India, Poland, Mexico—you can keep going—for a shot, a chance, to start a new life. For millions on the outside looking in, this is where they want to live, America.

And that’s why the semantics, twisted logic and debate over what is and what isn’t torture is so disturbing. We can concoct all the false rationales available. We can construct excuses based on the evil that occurred September 11th. We can go back and forth about the unknowable: Was torture effective? And we can listen to the pathetic, creepy bravado of a former vice president, wrong on nearly every decision he made. But all of it cannot erase the fact that our country is a 250-year-old testament to ideals that became blasphemy in the hands of a few while the nation reeled in a fear ignited on a single morning in September.

And if you want proof of what the country is really all about, just walk through the National September 11 Memorial Museum. Here it is, in the faces of the victims, in the stories of bravery, in the souls and memory of the survivors, the next of kin. The honored dead came from all over the world, from different lands, spoke different languages. They were rich, poor, black, white, brown, Asian, Hispanic, Catholic, Jewish, Muslim, Protestant. They were waiters, millionaires, stock brokers and salespeople, secretaries, firefighters, cops, young, old, their hopes, dreams, frustrations and futures incinerated by those who were and are twisted in their desire to destroy what all of us hold and too often take for granted.

During the week I happened to see a movie, Unbroken. It’s the film version of an incredible life splendidly captured in Laura Hillenbrand’s bestseller about the staggering story of Louie Zamperini.

He was a young Army Air Force lieutenant whose plane crashed in the Pacific in May 1943. He spent 47 days on a raft and survived only to be captured by the Japanese. He then spent two and a half years in various prison camps in Japan. And he was tortured repeatedly, brutally, and mercilessly by his captors. And he survived again, returning from the barbarism of war and the obscenity administered by others to rebuild and live a life once shattered by the horrific reality of what human beings are capable of doing to each other.

A couple of summers ago I sat with Zamperini at a ballgame at Fenway Park. He was a little guy, small in stature, but that was not who he really was because his heart, his being, his experiences, and the light in his eyes made you know he was actually the best of us: a believer in redemption, the future, the idea that we are all bit actors in the great American story where the strength of the country is stronger than any opposing force.

Zamperini died July 2. He was 97 years old. He lived through World War II, lived across all the decades in between, a time when we seemed to be constantly at war; the Cold War, Korea, Vietnam, Bosnia, Iraq, Afghanistan, generations of battle.

Too bad he is not still with us. I would have liked to hear what Louie Zamperini had to say in response to Dick Cheney’s declaration that torture was OK with him, a vice president of the United States of America.

https://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/12/15/dick-cheney-s-creepy-torture-bravado.html

The story of a mother, her son, the police who protected them, and the peaceful protest that brought them all together.

Alice Domingues came through the big crowd gathered last Wednesday night at New York City’s Columbus Circle, a container of Starbuck’s hot chocolate in her right hand as she held her son Micah’s hand even more firmly with her left. Earlier in the evening they took the train from the Bronx in order to see the Christmas tree lighting at Rockefeller Center, but were unable to get through police barricades set up at West 50th street, so they walked up Sixth Avenue in order to catch another train home.

“I can’t believe this,” she was saying, her voice hard to hear above the crowd noise.

“The marchers?” she was asked.

“No,” she said. “How much they charge in that place for hot chocolate.”

Alice wore a black nylon rain jacket that looked as if it was ill prepared to deal with the coming chill. She was young, perhaps in her mid twenties and clearly lives in that state of limbo created by the country’s inability to deal with the issue of immigration. Micah is 10 years old and he had a coat geared to the season, a Patagonia winter jacket with a hood.

“Like the hot chocolate, ” his mother said, laughing. “Expensive.”

She and her son had braved the madness within the Starbucks at the corner of Broadway and 60th as she bought a hot chocolate for the boy. She decided on the spur of the moment to join about 500 strangers who were marching north on the broad boulevard, their each step a statement of outrage over the refusal of a Staten Island grand jury to indict a New York City police officer in the sidewalk death of Eric Garner.

He died in July after being grabbed around the throat by a cop and wrestled to ground where the breath flew out of him. He was pinned to the cement for his refusal to go along with an arrest for selling loose cigarettes. The entire scene was caught on tape with a cell phone.

Now, mother and son started to walk. The crowd around them was as diverse as you will find: old, young, white, black, Hispanic, Asian, loud, proud, peaceful and oddly inviting. The reason they were in the street—attracting others to join—was that the grand jury’s act was thought to be so offensive to both common sense and eyesight.

A company of police officers surrounded the floating protesters. They were both in front of and behind the parade of people, making sure the marchers were safe from traffic, blocking off intersections as the peaceful legions proceeded toward Lincoln Center, posing no threat to anyone as they gave voice to a municipal outrage that would soon swell well beyond the borders of New York’s boroughs.

Ironically, the cops moving in the same wave were just as inclusive as the protesters: young, middle-aged, white, black, Asian and Hispanic, their every step non-threatening, their eyes non judgmental.

The New York City police department is more representative of the city it serves than most law firms, university faculties and media companies. According to the latest numbers, the membership of the NYPD is 47 percent white, 17 percent black, 29 percent Hispanic and percent Asian. Within the department there are officers who can speak or understand more than 60 foreign languages. Despite the actions of a flawed few, it is arguably the finest professional police force in the world.

Of course, the big difference between us and them, the eternal divide really, is that police have the power to use three simple words that separate them from any of us: “You’re under arrest.”

Cops can deprive people of their freedom. They are sworn to serve and protect. They work for us and they belong to, basically, a service industry, laboring in conditions that are sometimes threatening, often dangerous yet interesting. Cops, more than firefighters, EMT’s or other public safety employees, almost always get the first glance of the human condition at the worst, most lethal moments; nobody calls a cop with good news. A fire truck roars down a city street and people cheer its arrival. A cruiser shows up and eyes narrow and citizens often withdraw.

Wednesday evening and through the weekend people kept marching. The contagion spread across the country, to Chicago, Boston, Los Angeles and other cities where the fact of no indictment in the death of Eric Garner was thought to be incomprehensible and absurd.

And because of who he was—a black man—and how he died—in the hands of the police—the historical scar of race relations in America once more became the obvious story. Race is the San Andreas Fault of our culture as well as our history. Its fissures are forever present and not that far beneath the surface of every day life. To deny that is to risk being labeled delusional.

White folks can talk or write forever about being black in America without coming close to grasping the sometimes ugly aspects of life for too many back adults and their children. The idea that white commentators can so glibly prattle on about being black is as preposterous as the notion that seeing Saving Private Ryan makes you a combat veteran.

Who is more likely to be eyeballed in a jewelry store? In the aisle of Dick’s Sporting Goods? Waiting in line at an ATM? Walking at night on a quiet city sidewalk? Whose 17-year-old is instructed by a mother or father to keep his or her hands in plain view if a cop pulls them over for a busted tail light?

When he died, Eric Garner was a 43-year-old guy with a lot of health issues and too little money. He held no job. Like so many of the poor, he measured his future by hours and days. How much cash did he need to make it to supper? To the weekend? Before he became a legitimate symbol of suppressed and simmering outrage, he was like so many others among the battalions of poor across this country: a product of a two-tiered education system where the poor, black and white, are too often sentenced to inferior public schools where dreams go to die.

Now, the parade of protesters had reached Lincoln Center and the Wednesday night air was cold and constant and Alice Domingues’ son Micah had finished his cup of expensive hot chocolate. The cops blocked traffic coming down Columbus on to Broadway to let the peaceful march proceed, and Alice Domingues took the boy’s hand and headed toward the subway at West 65th to go uptown to the Bronx.

“How you doin’ kid?” a young policeman asked him, smiling.

“Okay,” the boy replied.

“Merry Christmas,” the cop said to both mother and son, making sure they got through the crowd, watching as they disappeared down the subway steps and toward home.

https://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/12/08/human-moments-at-the-eric-garner-protests.html

Meet the children at a small Catholic school in Massachusetts who will directly benefit from President Obama’s executive order.

So here they were, some of the people Barack Obama was telling the country about Thursday night, seated, smiling, clearly happy, and outfitted splendidly in the first-grade classroom at Lawrence Catholic Academy, a new school located in an old building put up in 1905. The kids, about 20 of them, paid rapt attention to their teacher, Jeanne Zahn, widow of a firefighter, as she asked them what their favorite subject was.

“English,” said a little girl.

“Math,” a boy added.

“Religion,” another girl added.

“Gym,” a second boy said to laughter.

With one exception, the children were all Hispanic. The city, Lawrence, Massachusetts, is located about 30 miles north of Boston and is home to 76,000 people. It is 74 percent Hispanic. It is one of the poorest places in the United States with 27 percent of its residents living below the poverty line. The average per capita income here is $16,557.

In the early morning before school begins, many children arrive holding the hand of a parent who is in America without documents. The parents are wild with pride because their kids attend a fine parochial school in an old, battered New England city where the public school system is in virtual collapse. The parents are also acutely aware that due to the fact they have no papers they are prime targets for the mentally ill wing of a Republican Party that is so obsessed with Barack Obama’s every action that it has seemingly forgotten or willfully ignored the foundation of the nation they claim to represent.

And Lawrence, even now, is a symbol of that story, one of history’s greatest tales: a magnet across time for people who came here from Ireland, Poland, Greece, Italy, and Russia to work in the near-empty mills that sit along the Merrimack River like hollow, brick catacombs.

“They came then for the same reasons people come here today,” Father Paul O’Brien, pastor of neighboring St Patrick’s Parish, was saying in the first floor hallway of the school. “They come, some of them, out of desperation. They come seeking a better life, a job, a hope for the future.

“Look,” he added, “Christ went into refugee status after he was born. And this whole debate about who is here and who belongs and who has to be deported has become so disconnected by TV news shows and our polarized politics that it has very little connection to our history or our day-to-day lives. So the idea that people in public life are not saying, ‘How can I help you?’ and are instead saying, ‘Get out of the country,’ is beyond me.”

“How many have parents who are undocumented?” the priest was asked.

“We don’t ask?” he said. “They’re here. They’re working. The politicians might say they have to go back but they won’t. I’d like to know when was the last time some of these politicians ever sat with or got to know an illegal immigrant or their families. If they ever have.”

The school, Lawrence Catholic Academy, has 500 students. It covers kindergarten through 8th grade and has $3,825 annual tuition, but fundraising allows many to get $1,500 in tuition aid. Only 25 percent pay full tuition.

“And we have a lot of parents who pay weekly with cash or money order because they don’t have a bank account due to the fact they are fearful they will be identified as being here illegally,” the principal, Jorge Hernandez, pointed out.

Hernandez is 37 years old. He went to Catholic schools as a child because his parents sought both education and accountability for him. He won a scholarship to Villanova and ended up here in Lawrence.

“It reminds me of where I grew up,” he pointed out.

“Everything about it reminds me of it. I see myself in each and every one of these kids here at school. I’m here to pay it forward.”

His parents left Guadalajara, Mexico, with no papers just before he was born in Los Angeles. His father, who had only a second-grade education, worked in an El Segundo sheet-metal factory, rising to foreman, all the time working and living in the same shadow of fear and uncertainty that hovers over those here without documentation now.

“His life, my mother’s life all changed with Reagan’s amnesty,” the principal pointed out. “Then, the threat of being deported was finally lifted.”

The old-fashioned yet eternal concept of Catholic social justice is thick in the hallways and classrooms of Lawrence Catholic Academy. And it is stronger and deeper than the momentary flood of hypocrisy and polarization that has left so many disgusted and disappointed in the arm-waving, vote-seeking, hysteria-driving members of Congress. The ones who suck up a public paycheck while trying to divide the country with language and behavior that offers visible daily proof that much of our politics has now gone right off the rails.

Obama’s action Thursday night will allow a few million residents of the United States to stop worrying about a traffic stop for a broken automobile tail light. That leaves perhaps as many as 7 million more here illegally, frightened that they could be discovered and shipped out at any moment.

Of course, the illogic surrounding the staggering task and cost of gathering millions and transporting them by plane, train, and automobile back to the Dominican Republic, Brazil, Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Panama, and several other countries is never discussed. This is because the only location that debate could take place would be in an asylum.

Now, some of the kindergarten children were standing straight as soldiers in a line at the door of their first-floor classroom. They were bundled in heavy coats worn over their school uniforms as they got ready to go outdoors led by their teacher, Sister Ellen, a member of the Sisters of Charity.

“I’ve been teaching kindergarten here in this building for 44 years,” she proudly declared. “And before that I taught kindergarten in another school for 21 years.”

“What? How many years?” she was asked.

“Sixty-five years altogether,” she pointed out with a laugh. “I must be crazy, right?”

“How old are you?”

“Eighty-four, and by the way aren’t these kids great,” she wanted to know, helping a little girl with the zipper of her jacket.

“What about people who want them deported?” she was asked.

“They’re not going anywhere,” Sister Ellen declared, smiling. “They’re going out to recess.”

https://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/11/24/freedom-from-fear-for-dreamer-kids.html

Riding around Manchester with Lou D’Allesandro as he rounds up votes and frets over Senator Jeanne Shaheen’s chances against Scott Brown

MANCHESTER, N.H.—Here he is in his campaign headquarters, the front seat of his Toyota Camry, driving along downtown Elm Street, past banks reluctant to lend, storefronts somewhat empty, and people living paycheck to paycheck in a state, country really, where take-home pay is perhaps the largest issue beneath the surface of a season filled with voter anger toward a stagnating government: Lou D’Allesandro, 76 years old, a New Hampshire state senator for 20 years, a Democrat on Tuesday’s ballot, a living reminder, a relic perhaps, of a time when a politician’s principal task was listening to constituents and performing.

He takes a left on Bridge Street heading toward the west side of a city where he represents nearly half the citizens. He is wearing a blue UNH pullover, blue shirt, tan pants, and a perpetual smile, and is talking about the race for the United States Senate between incumbent Jeanne Shaheen and Scott Brown, who used to be in the Senate and used to be from Massachusetts, when his cell phone rings.

“Hello,” Lou D’Allesandro, one hand on the wheel, says, a smile in his salutation. “Nick, how are you? …Yes, Nick … I’ve arranged for your daughter to get that job … It’ll be part-time to start and then I think we can get her on full-time … She’s got to go to work every day, Nick … Can’t quit, okay? … Good, I’ll get back to you tonight with the particulars … Okay, talk to you later.”

And here it was, the definition of politics: a full-service industry before it fell hostage to consultants, focus groups, pollsters who have turned the simple proposition of helping people into an expensive assault on the senses of anyone simply trying to live a normal life.

At one level, campaigning remains an art of sidewalk commonsense, one not totally reliant on tools like Twitter, Facebook, blogging, commercials, cable TV, or radio talk shows. Few things can compare to the social cement of a firm handshake, a genuine smile, recalling a name, remembering a favor asked and a favor found. All that is old-school and a disappearing discipline.

“Now, there’s a great sign,” he says, pointing to a “D’Allesandro for Senate” poster at the top of the rotary where Bridge Street joins the west side of Manchester. Beneath the bold lettering there is a picture of Lou and his wife Pat, both smiles brighter than street lamps.

“Jeanne has some good signs around too,” he says, heading down South Main Street. “I think she’s going to win it Tuesday. She’s got a good ground game and nobody dislikes her. Plus, he’s not from here.”

Shaheen is New Hamsphire’s senior senator and the state’s former governor. She is fighting a strong, well-funded opponent in Brown, who lost his Senate seat to Elizabeth Warren, who beat him like a rented mule when he lived across the border in Massachusetts two years ago.

“I think she was surprised at how many resources the Republicans poured into New Hampshire to beat her,” D’Allesandro says of Shaheen, taking a right on Mast Road toward Sarette’s garage, past Jacques Flowers and Dickie Boy Subs.

“Donnie Russo,” Lou says, quietly, “He owned Dickie Boys. Hard worker. One of 13 kids in his family. Never gave me any money for the campaign but he’d feed us election nights. Died young. In his fifties. Massive heart attack. Wife’s a recovery-room nurse. Wonderful woman. Just helped get her a passport.

“But this guy, Scott Brown, he’s everywhere. He’s made for retail politics. He’ll crush a shopping mall, shake every hand. Then he’ll go on TV and get in the debates and try and scare people telling them the Taliban is crossing the border with Ebola. Crazy.”

Lou pulls into the lot at Sarette’s, where regular gas is $2.99 a gallon. He starts laughing as he sees Bill Sarette walk toward him. D’Allesandro spent a morning last week pumping gas for customers here.

“Billy, I didn’t tell ya,” he says, “but this one woman came in, told me to fill it up and I did. Fifty-one bucks worth and then she tells me all she’s got on her is 20 bucks. Cost me 31 bucks to work for you.”

“Hard times, Lou,” Sarette says, laughing.

Sarette, is 54, one of eight children. The business began with his father and the son has been here “all but two years of my life. I wasn’t here when I was 19 and 20. Two fun years. Other than that, right here.”

Sarette is a Republican who pays little attention to party labels. “I’m voting for Jeanne,” he declares.

Why? “The guy isn’t even from here,” Sarette says. “He says he’s from here because he has a summer camp or something here. Hey, I’m not a moron. He doesn’t know me. He doesn’t know us.”

“Still a small state,” Lou D’Allesandro adds, “and a small town. It’s about relationships. Look at me: Fifty years in the same house. Fifty years married to the same woman, the magnificent Pat. The business is about more than TV ads or handshakes, it’s about relationships.”

“You got that right, Lou,” Sarette agrees.

Now, state Senator Lou D’Allessandro, former teacher, high-school football coach, college athletic director, instructor at the New Hampshire Institute of Politics, is back behind the wheel, taking a right on Boynton Street, driving a mile or so before pulling into a gas station owned by Saeed Ahmed.

Ahmed is 39. He was born in Pakistan and came to Manchester in 1999. He is married with three children. He is now an American citizen, and he rushes out of his station as soon as he sees D’Allesandro, as if a wonderful gift has just arrived.

“My friend, my friend,” Ahmed says, hugging Lou, shaking his hand. “I was going to call you today. I need more cards. More signs too.”

“Remi,” D’Allesandro says to his campaign manager Remi Francoeur, who is with him, “can we get Saeed more cards and signs today?”

“Done,” Francoeur says.

“Saeed came here speaking no English,” D’Allesandro says. “We helped him with that. Helped him start a business. Helped him get a loan. He pays all his bills. He now owns three stations—two in Manchester, one in Derry. His kids are in school here. He owns his own home, pays his taxes. He is a great American.”

“Whatever you need,” Saeed Ahmed tells his state senator. “I’m for Shaheen. I’m for you. I’m for America.”

Now Lou is back in the car, driving along the Merrimack River and the old brick factories that formed the spine of the Amoskeag Mills, once the economic engine, the paycheck, for thousands. Many of the buildings have been brought up to date and now house other, newer, smaller companies. New Hampshire, like so many other states in the northeast, has seen the work go from wool to shoes to electronics to finance. They’ve seen the work go to North Carolina, Texas, and other regions as history and a corporate lust for lower power costs and bigger tax incentives have left so many behind with smaller paychecks, haunting economic insecurity, and incomes that simply do not keep pace with the cost of getting through a single week.

“She has to win,” Lou D’Allesandro is saying about Jeanne Shaheen. “And I think she will because she has a much better get-out-the-vote operation. It’s close but she’ll win I think because people know her. They’re angry at Obama, at politicians in general, at no jobs, at a lot of things but you can’t eat angry. You can’t eat fear.”

As he says this, he is pulling into the parking lot of the Puritan Backroom restaurant. There, he bumps into Irene Messier, who is 92 years old.

“Lou, I already voted for you. Early voting and I voted for you and I voted for Jeanne too.”

“Thank you, Irene,” Lou D’Allesandro, a man fully invested in politics and people tells her. “I really appreciate it. It’s always better to be one ahead than one behind. Thank you.”

https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2014/11/retail-politicians-running-out-of-stock/382220/

Sarah Glenn/Getty Images

Bobby Valentine needed a coffee.

It was five minutes to seven on a soft spring morning at JetBlue Park in Fort Myers, Florida, and the 61-year-old manager of the Boston Red Sox had just arrived in his office — a windowless room located on a long cinder-block corridor within a baseball facility built seemingly overnight in a state where high unemployment, low union clout, and Lee County official eagerness resulted in farmland being turned into a state-of-the-art ballyard in stunning speed.

“Forgot we had a night game,” he said. “I could have gotten here a little later if I remembered we were playing a night game today.”

“What time would you come then?” he was asked.

“8 a.m.,” he answered. “Kitchen’s not even open yet. I need a cup of coffee. One cup. That’s all I need in the morning. One cup to get me going.”

There was a coffeemaker on top of a hip-high steel file cabinet along the wall behind his desk. Valentine stood up, placed a coffee cartridge in the coffeemaker, and touched the “on” button with his index finger. Nothing happened.

“Jesus Christ,” he muttered. “Is this thing working?”

He pushed the “on” button again. And again, nothing. Then he moved the file cabinet away from the wall, removed the coffeemaker’s plug from the outlet, and put the plug into a second outlet. Still nothing.

“Goddammit,” he said. “That’s distressing.”

He hit the switch a third time and then hit the coffeemaker. Now he stood staring at it with the same look he’s given countless times to players who failed to hit a cutoff man or missed a bunt sign.

“I’ve got to get this thing working,” he said to himself. “Watch, I’ll get it working.”

“You sound like a know-it-all,” he was told.

“Hey,” he laughed. “That’s probably because I am a know-it-all.”

So, here he was, Bobby V, the pride of Stamford, Connecticut, greatest high school athlete in that state’s history, nine years out of the major league managerial loop, standing in his baseball underwear, cursing a coffeemaker, carrying all the baggage as well as optimism that has clung to him across a lifetime in the game.

“I’ve learned to not dwell on the last loss,” he pointed out. “I now prefer to think of the next win.”

This week he takes a team — the Boston Red Sox — into a season still in the shadow of a disastrous September collapse and a nightmarish offseason; the manager, Tito Francona, departed, followed by the general manager, Theo Epstein, amid a series of news stories that made the club appear more dysfunctional than the cast of Jersey Shore.

He has a permanent smile on his face and an iPad on his desk. There is a stack of unopened mail on a round table. There are several books next to the letters: People Smart by Tony Alessandra and Michael J. O’Connor, The Leader Within: Learning Enough About Yourself to Lead Others, by Drea Zigarmi and Ken Blanchard, and Thinking, Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman.

“Kahneman,” Bobby Valentine notes. “He was awarded the Nobel Prize.”

So who is he in this, the spring of his 61st year, more than 40 of them spent in baseball? Is he, as a critic like Curt Schilling contends, an overmanaging control freak who eventually exhausts both players and the front office with constant tips on how to lay down a bunt, turn a double play, round third, load an equipment truck, make a sandwich, or select a wine? Or is he simply a guy whose high-wattage personality, eternal optimism, endless curiosity about multiple topics, love of the game, and substantial IQ and EQ (emotional intelligence) have him roaming across various facets of life as if each sunrise came with a buffet of big thoughts to be sampled or devoured? A guy who has managed to assemble all his experience into nuptials where instinct finally marries wisdom?

For years — before he was either banished, forgotten, or thought to be too electric to handle — Bobby Valentine played and managed games from eye level. And while he remains unafraid to grade his new club, his absence from the scene — as a true participant with a number on the back of his jersey — seems to have brought a caution about where his rhetoric might lead when conjecturing about the record and road ahead for the 2012 edition of the Red Sox.

Through the time in Texas and New York, he was a man of the moment. Always there with something to say about nearly everything and everyone; 162 games, 162 potential chances for combustion. But life in Japan and working for ESPN did something that probably surprised even him: It broadened his horizons, exposed him to different styles of management and leadership — and Valentine is a sponge for anything he thinks might give him an edge. He absorbed all of it and now takes those lessons to this job, this team, and a town that has been waiting in judgment since Evan Longoria’s home run landed in the left field stands last September, cementing a historic Red Sox collapse. And he is indeed ready to be judged, booed, cheered, second-guessed constantly, and have the F-word used as an adjective before his last name if the Olde Towne Team doesn’t come out of the gate playing .800 baseball.

“I understand expectation and I understand there’s only so much you can do about the perceptions others have about you,” he says. “Actually, there’s not much you can do. But I’m older now; I’m more interested now in building my character and not my reputation. That wasn’t always the case, though.

“I don’t really get concerned or caught up with what people think of me anymore. That’s reputation. I know that sounds like a line, but it’s a fact. I try to do what’s right as often as possible … that’s character.”

First time he got fired, he was about 15. He was working in a clothing store in Stamford called Frank Martin and Sons.

“I was selling clothes,” he recalls. “I guess I wasn’t very good at it, so I got fired. I was surprised, but I wasn’t crushed.

“I got fired in Texas. Got fired in New York. I survived. Got through it. It’s all part of life’s lessons, and I’m still learning. Hopefully, every day.”

Now he finds himself back at work, back in uniform, in a market that can often feel claustrophobic. Since 2004, when the Red Sox beat the Yankees in an earth-shaking, universe-altering, come-from-behind playoff series for the ages and then, seemingly as an afterthought, won the World Series, too, “The Nation” greets each season with high expectations and low patience. Valentine was hired during a winter of chicken-and-beer tales, and each new story and every day only seemed to add to the clamor and anger that came with the collapse.

“I don’t think I was hired to change the culture of the team,” he says. “I don’t think there is a culture that needs to be changed. I see a group of players, very good players, who know how to play the game and play it very well.

“Now, the culture of the game itself,” he continues, “well, I do think there can be some changes, some adjustments if you will, that I’d like to help happen. Maybe a little reversion to Baseball 101.

“Here’s what I mean: I’ve noticed that across the last five or 10 years in the game there seems to be a growing tendency to wait for the home run. And I think that’s dulled the senses a little bit, the baseball senses. And I don’t think that waiting for the home run to occur is fulfilling enough for a baseball player.

“Baseball players know instinctively that there is much more to this game. I walk around the locker room and I see Adrian Gonzalez and Dustin Pedroia and Jacoby Ellsbury sitting around talking with Dave Magadan, talking about baseball, talking about all the little things that make up the game, the things that help a team win, things other than the home run, and it makes me happy. They get it.”

And Valentine got it, too, got the one thing he thought he might never get again: the chance to manage another major league team, to measure his day by innings instead of by wristwatch, to think of what he might want to do in the top of the eighth during the bottom of the third, to live and breathe every moment from eye level in a dugout instead of off a TV monitor in the press box, to again be the real Bobby V rather than Bobby Valentine, analyst on Baseball Tonight, former manager of this club or that one.

He is semi-fluent in Japanese. He is a gourmet cook, a ballroom dancer, inventor of the wrap sandwich, a consumer of Malcolm Gladwell’s books as well as sheet after sheet of sabermetrics; he has been fired by George W. Bush, worn a disguise in a dugout, colored his hair for TV, and never, not once, missed an opportunity to grab life with both hands each and every day.

He is Bobby Valentine, back in the game, back in the one place where he feels most at home, most comfortable: a dugout, with a lineup card in his grasp, a field in front of him, and a long season of hope and opportunity ahead with one objective, the single item that has driven him through the years.

“The win, baby,” Bobby Valentine said. “The win.”

BY MIKE BARNICLE

It was nearly dusk, the weak winter sun finally surrendering for the day, and Kevin White was leaning against the brass rail that stood in front of a wide glass wall as he looked at the view from the mayor’s office, down toward Faneuil Hall and Quincy Market. It was close to Christmas and people below walked through oatmeal-colored slush to shops that glittered in the approaching grey of late afternoon.

Look at it, “ Kevin White was saying then. “Look at all the people down there. Ten years ago the place looked like a stable. Now it’s a palace.”

A thief called time has stolen more than three decades since he stood at that window. And a vicious illness called Alzheimer’s robbed him of memory, slowly pick-pocketing what he knew and loved about his family, his friends, the substance of his days, his accomplishments, his election wins and losses, his pride in appearance and, finally, his life.

Remarkable urban fact and extraordinary political reality: Kevin White was one of only four mayors to govern Boston across the last 50 years. Half a century: Four men!

He arrived at the old city hall on School Street, having defeated Louise Day Hicks who knew where she stood on race and schools and busing in the fall of 1967 after a bruising campaign that held the outline of a fire that would nearly consume the town seven years later. He had been Massachusetts Secretary of State since 1960 and he was an odd element added to the tribal politics that then dominated Boston.

Kevin White was always more Ivy League than Park League. He felt more at home in Harvard Yard than he did at The Stockyard. He was Beacon Hill more than he was Mission Hill. He knew all about Brooks Brothers and not much at all about the Bulger Brothers. He read history rather than precinct returns. He was neither a glad-hander or a back-slapper and other than his wife, his family, a few close friends like Bob Crane, the former Treasurer, and a couple others involved in politics, he had a distance about him that kept him from succumbing to the two items that have proven to be a death sentence to so many others around Boston: Resentment and envy. White was a big-picture guy in the small-frame city of the mid-20th Century.

He enjoyed politics the way chronic moviegoers enjoy a good film: For the plot, the storyline and, most of all, the characters. His appreciation for the business of elections was borne in part through his father Joe who was on so many municipal payrolls when White was growing up that he had earned the nickname, “Snow White and The Seven Jobs.” And there was his father-in-law, “Mother” Galvin, who dominated politics in Charlestown and defined a mixed marriage as an Irish girl marrying an Italian.

The first time he met John F. Kennedy was on the tarmac at Logan Airport in October 1962 when the President of the United States came to speak at a Democratic State Committee dinner at the old Armory on Commonwealth Avenue, across from Braves Field, now all gone, replaced by gleaming new dorms and a Boston University athletic center.

White was running for re-election as Secretary of State. The statewide candidates were told they had a choice: They could meet the President at the airport or they could have their picture taken with him at the black-tie dinner that evening but they could not do both.

“When he came down the steps of Air Force One, it was like the Sun-King had arrived, “White once recalled. “And then when he said what he said to Eddie McLaughlin I realized how different he was from anyone I had ever met before.”

The late Edward McLaughlin was then Lt. Governor of Massachusetts and he was first in line to greet Kennedy. And, unlike White and the other statewide candidates there, he wore a tuxedo. He was going to get his picture taken twice.

“I will always remember the twinkle in Kennedy’s eye when he saw Eddie in the tux, “Kevin White remembered. “He touched Eddie’s lapel and said, “Eddie, taking the job kind of seriously aren’t you?’ God that was funny.”

Through four city-wide elections, two of them – in 1975 and 1979 – knock down, hand-to-hand combat with former State Senator Joe Timilty and the searing, bleeding open wound that was busing, White’s ambition for any higher office diminished and disappeared, replaced by a desire to grow the city from a place of narrow streets and even narrower vision into a wider arena where people would come, go to school and stay; where development would flourish and provide a new coat of paint for a tired relic of a town that had a death rattle to it in the early 1970’s; he wanted to put his little big town on a larger stage for the world to see.

Kevin White was unafraid of talent, a big asset in attracting those who turned ideas like Quincy Market, Little City Hall, Summerthing and Tall Ships into a reality that helped the city grow up rather than simply grow older. Downtown began to flourish at the same time different neighborhoods retreated into a type of municipal paranoia, a kind of virus that spread block by block, transmitted by a near-fatal mixture of political incompetence, cynicism, racial tension, class conflict and inferior schools where – no matter where buses dropped off students – the ultimate destination for too many kids was a dead end when it came to a great education and a better life.

Those years, Judge Garrity’s ruling, blood in the streets, two campaigns against Timilty, the increasing self-imposed isolation within the Parkman House, exhausted White but he never surrendered to bitterness.

No mayor of Boston before or since has had to deal with the tumult, the division, the demands of a federal court, the need for the city to grow or die, the ingrained cynicism and the perpetual parochialism that has been as much a part of our lives around here as air. Kevin White did it, with more wins than losses.

If you are new to town or if you have never left, look around this morning as you drive to work, go to lunch, walk the dog, wait at a bus stop, emerge from Park Street Under, run along the Charles. There is no need to read any obituary of Kevin H. White. You are looking at it. You are part of it. It’s called Boston in the 21st Century.

He is one of 70 from Iowa killed in Iraq or Afghanistan fighting two wars that have had so few serving for so long as America plods into the second decade of a new century, exhausted and isolated from battles that crush the families of the fallen at home.

“I was just looking at a picture of Tommy and his older brother Joe,” Mary Ellen Ward was saying the other day. “It was taken on Oct. 31, 1987.

“He would have been about five years old. His brother was seven. A Halloween picture. Joe was dressed as a Ninja. Tom was in camouflage. He always wanted to be a Marine.

“The last time I talked to him was Christmas Day, a few days before he was killed. He was going to play flag football in the sand. He was on his second tour.”

“How old was he,” his mother was asked.

“Twenty-two,” she answered. “He was only 22.”

“It’s funny,” she was saying, “but the last time he was home, just before he left for his second tour of Iraq, we went shopping, just the two of us. And I had this feeling, this strange feeling, that I’m never going to see him again. I knew…I just knew.”

Across Iowa, the candidates appear in cities and towns like fast-moving clouds pushed across the flat landscape on a wind of ambition. Here is a Gingrich, then a Romney, a Santorum, a Paul, a Bachmann or Perry smiling, glad-handing, promoting, promising, pleading to be sent forward to New Hampshire and beyond by the handful of Iowans who will show up at caucuses Tuesday night.

“I don’t have much interest in it, politics,” said Mary Ellen Ward, who works for the state Child Support Recovery Unit. “And I kind of hate to say this but I think we ought to get everybody out of there, out of Congress. Why does it cost so much to run? I don’t understand that. Why do they get free health care, better health care than the rest of us do, for nothing? They get a nice pension too. They shouldn’t be serving more than two terms either. And none of them talk about the wars. It’s like it’s not there to them.”

She lives with her husband Larry in a city framed by the mythic elements of the country’s history. Council Bluffs sits at the edge of the great Missouri River, separated from Omaha, Neb., by waters that divide two states and dominate the landscape. It was once a huge railroad center when America moved mostly by train, before the automobile, the interstates, long after Lewis and Clark came through on the way to the Pacific.

The town, like most, has a narrative to it, a story that is both parochial and universal: It was built by pioneers who suffered and prospered yet greeted each sunrise with a sense of optimism.

Now, in a country confronted with and confused by political people, including an incumbent, all submitting a job application for the position of president of the United States, anxiety about the immediate future fills the air. The economy has flat-lined for three years. Washington is totally isolated from the rhythms, the mood, the fears and apprehension felt by most Americans. And the wars drag on, touching only the few who serve and their families who remain here, praying nobody knocks on the door at night to tell them a sniper, an IED, an ambush or a fire-fight has claimed a son, husband, daughter or dad.

So on Jan. 3, 2012, as candidates organize and hope for a finish that will fuel a continued campaign, Mary Ellen Ward will again – and daily – think of her son Tommy: Sgt. Thomas E. Houser, USMC, 2nd Force Reconnaissance Company, First Marine Division, killed on this day in 2005 in Iraq.

And she will barely notice the passing parade of politics because she has other concerns, another worry, one more mother’s burden: Her oldest boy, Joe, is scheduled to depart with the Marines in two months. For Afghanistan. For another tour in a war that has made much of our nation weary and too many of our politicians silent.

Mike Barnicle is an award-winning print and broadcast journalist and regular on MSNBC’s “Morning Joe”.

Deadline Artists: America’s Greatest Newspaper Columns

Edited by John Avlon, Jesse Angelo & Errol Louis

At a time of great transition in the news media, Deadline Artists celebrates the relevance of the newspaper column through the simple power of excellent writing. It is an inspiration for a new generation of writers—whether their medium is print or digital-looking to learn from the best of their predecessors.