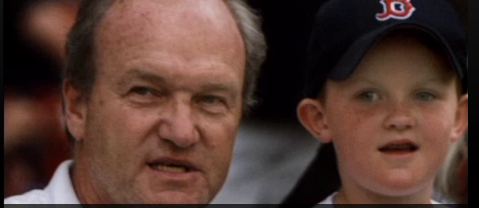

With husband Bob, Myra Kraft attended many fund-raisers, smiling and greeting donors. (1997 File/The Boston Globe) |

On Morning Joe today: Mike tells the terrible story of how a wasp flew into his ear!

He says: “It was awful!!!!” and more….

Mike is quoted by Joe Scarborough on Morning Joe … giving his best advice for parents:

Listen here:

MIKE SHARES MEMORIES OF FENWAY PARK

Thu Apr 19, 2012 2:50 PM EDT

Evelyn C. Savage

Our man Mike Barnicle has talked a lot and written a lot about Fenway Park over the years. Lately, he’s been talking a lot about the park’s 100-year-anniversary, which will be celebrated Friday, April 20th with a game against the Yankees that begins at 3:05 p.m. (the time the Sox began their game against the New York Highlanders). Hearing Barnicle discuss his first visit to the park in the mid-1950s is hearing his rite of passage story. It seems safe to say he views Fenway as his second home, if not maybe his first home.

I spoke with Barnicle this Wednesday about the big anniversary, his relationship with the park, why he doesn’t heckle the team during a game, if there’s any rival to Fenway, and whether it was his father or his mother that was the big baseball fan in his family.

Morning Joe: Why does Fenway hold such a special place in the hearts of not just Bostoners, but seemingly all New Englanders?

Mike Barnicle: I think, in large part, it’s because of the permanence of the facility itself. When you consider the fact that we live in a time now where people move almost relentlessly. Very few people live in the same house they move into when they’re married or the same neighborhood when they’re married. Very few people certainly live in the neighborhood they grew up in. We change all sorts of things in rapid time. We sit here in front of TV sets with clickers in our hands, and change channels. We change spouses and partners; divorces are epidemic considering to what the divorce rate was 30 or 40 years ago. All of these things that we’re used to today, these elements of change that are around us, to some people and maybe to most people at some level within them, can be kind of disconcerting. Like ‘Jeez, that place used to be a drug store when I grew up.’

MJ: And now it’s a parking lot.

Barnicle: Now it’s a parking lot or a high rise or a McDonald’s or whatever. And then you get to Fenway Park. And it is the same today in large measure as it was the first day you walked into that park when you were seven years of age holding your father’s hand. And there’s a sense of permanence to the ball park that gives people, I think, a feeling of security or a sense of sameness to the area; that gives a lot of people a sense of happiness. It’s still the same today coming up out of the subway stop at Kenmore Square. Walking through the square, up across the bridge on Brookline Avenue to Lansdowne Street. The light stands. It’s the same. The bricks are the same. And I think in an age of constant change and great change, I think that brings a huge measure of relief to people.

MJ: And it’s something you hand down from generation to generation.

Barnicle: Yeah. As your father or grandfather, depending on your age, took you 40 years ago, 60 years ago, whatever, however old you are, 20 years ago, you can take your son or daughter to the game today and then hopefully 20 or 25 years from now, they can take your grandchildren to the game, and it will be the same.

MJ: I don’t know the reasons why it has stayed where it is and parks like Yankee Stadium or Shea Stadium have not. Can you give a general primer why Fenway Park hasn’t moved in a 100 years, given that it’s a very busy, bustling area now?

Barnicle: There are a couple of reasons why it has remained where it is and remained pretty much the way it has always looked. The biggest reason right now is after the sale of the team in 2001. The debt service to build a new ball park in another area of the city – say down by the waterfront – would have been too heavy for the present ownership group to carry. They didn’t want to carry the debt service, having just paid a record amount of money for the team and for the ball park. They didn’t want then to transfer the debt service that they were already carrying to the increased debt service of construction for a new ball park. That’s one reason. That’s a financial reason, obviously.

But there’s another reason, and it is this: That one of the members of the ownership group, Larry Lucchino, who came in in December 2001, was the guy who built Camden Yards in Baltimore. And built it in the early ‘90s; I think it opened 20 years ago. It’s been open since 1992. Built it with an idea that a ball park around Camden Yards – the old railroad yards in Baltimore – would create, he hoped, the establishment of a brand new urban neighborhood, which it did. And the refurbishing and rebuilding of Fenway Park since 2001 has created a new urban neighborhood in Boston. It is now a very hot neighborhood and is continuing to grow hotter and will only increase in attractiveness to both residents and businesses. Because the ball park is a magnet. It is the single largest tourist attraction in Boston now and it’s not just a six or seven-month-a-year facility. It’s open all year round. You can have a wedding at Fenway Park.

MJ: Have you been to a wedding there?

Barnicle: I have. I’ve been to bar mitzvahs at Fenway. It’s created a thriving, fairly young and affluent neighborhood around the ball park, which is something that did not exist prior to rebuilding the place.

MJ: And it is centrally located in the city.

Barnicle

: That’s part of the magic of the park as well. If you’re there for just a few days in Boston, you can walk to the park. You can be staying around Boston Common; you could be staying with friends in Jamaica Plain. It’s easy to get there. It’s not exactly great to park around there, but what ball park is great to park around? You can get there fairly easily.

MJ: It seems safe to say you’ve done this many, many times in your life, but I have to ask about your memories of your first time at the park. And where did you sit in the park as a child? And where do you sit now?

Barnicle: The first time I went to Fenway Park was probably 1950. It was the early ‘50s, and it was my father taking me to the game. And what I have full retention of is of the electric sight of coming up the ramp on the first-base side (and it’s still the same sight today), and you come up into the splendor of green that you see in front of you. The lawn, the wall, the sun sparkling on both. And when you come up the same ramp today for a day game or night game, it’s still shockingly beautiful. At least it is to me. The ball park itself…where did I sit? We used to sit when I was a kid – tickets were obviously cheaper then – we’d sit in the Grandstand section. Maybe section 15 or 16, which is along the right field foul line.

But you know, things change. You go to work; you get lucky; you do well; you make a little money. Some people buy beachfront property. I buy season tickets. So, I have and have had for quite some time, ten season tickets in various locations around the ball park, all pretty good seats. The seats I sit in are right by the Red Sox dugout. And I’ve sat there for years.

MJ: Where you proceed to heckle the team all season?

Barnicle: You know what, not only do I NOT heckle the team, because I have an appreciation for how difficult that game is to play. But if you would watch me during a game — and please don’t — I only rarely show any emotion at all. Like standing up or cheering or clapping. I like to just watch the game. And I do not enjoy taking people to the game who want to talk about anything other than baseball and who don’t get the fact that, you know, ‘Hey, I’m trying to watch the game. You want to talk about what’s going on in the game, feel free. But don’t be talking to me about your hedge fund.’ But that would be very unlikely for me bringing a hedge fund guy to sit with. But you get the point.

MJ: So there’s a hierarchy of mental involvement when it comes to watching the game, and you like to focus is basically what you’re saying.

Barnicle: Yes.

MJ: If you’re going to Fenway for the first time, what are the rules of going to a game?

Barnicle: You should enjoy where you are, first of all. Because there’s not a facility like it in the country for baseball.

MJ: What do you mean by that?

Barnicle: The field is quirky in its arrangement. It’s not like a cookie cutter field. It’s not like 325 down the line at left, shoots out to 345 at left center, 410 in center, 345 in right center, 325 down the line at right. It was designed at an earlier, easier time. You’ve got the famous wall, and they post it at 310, but it’s probably about 300 feet from home plate. Not a big distance for a major league hitter. The wall was put up to prevent mud slides, really. The park was built on a landfill. There’s a crazy, cookie-cutter design to center field. There’s a corner of the bull pen that makes it one of the deepest center fields in the major leagues. It’s got a wide, horseshoe-shaped right field that if the right fielder misses the ball on the bounce, the ball can carom like a pinball all the way around. You can get yourself an inside-the-park home run. It’s interesting. And it’s different from most parks.

MJ: Is it safe to say Fenway is your favorite park? Is there a rival in your mind?

Barnicle: Wrigley Field [in Chicago] is pretty nice. Almost as old. Where the Cubs play with the vines on the wall on left field. And it’s in a great neighborhood, as well. Like with Fenway, it’s a magnet for a younger crowd. That’s a nice ball park. Some of the newer ball parks are really nice. The ball park in Pittsburgh is a spectacular ball park. Again, it’s right downtown. The Denver ball park, built in the LoDo area, completely brought back that neighborhood. San Francisco has a fabulous ball park. It’s right down in the Embarcadero. You can walk there from downtown San Francisco.

And there’s a difference, too. If you want to play baseball, you want to play in a park and not a stadium. It’s nothing but rhetorical, but a stadium symbolizes something larger. You’re going to play football in a stadium. A park connotes someplace you come, it’s smaller and more comfortable.

MJ: What do you remember about the team when you first went to a game?

Barnicle: I can remember many specific players. Jimmy Piersall, Number 37. Sammy White, the catcher, Number 22. Ted Williams, Number 9. Harry Agganis, Number 6, died of pneumonia in Santa Maria hospital in Cambridge after a road trip in 1955. I can remember all of that. I can’t remember what I had for breakfast this morning, but I can remember that.

They were a dreadful team then. Always finished in fourth place. There was an A-team American League division then. There were only 16 major-league teams. I could remember most of the teams. Most of the teams that played the Red Sox would stay in the Hotel Kenmore in Kenmore Square. You could camp out and get autographs because the players would just walk the 150 years to the ball park. Every team stayed there with the exception being the Yankees. They stayed at the old Statler Hilton in Park Square in Boston. I can remember vividly much of that period of time.

MJ: You mentioned your father taking you to your first game. What kind of a Red Sox fan was he when you were younger?

Barnicle: He was not a huge fan, turns out thinking back on it. He took me because I loved baseball.

MJ: So you asked him to take you?

Barnicle: Yeah. He liked baseball, but he was nowhere near the baseball fan that I was then and obviously became. He was like most people his age in that era. Newspapers cost two cents each, so we used to get six or seven newspapers a day in the house. And you’d follow almost everything through the newspaper, baseball included. My mother was a big baseball fan. She loved Ted Williams. She would sit on the front porch of our home, with the radio on and listen to the ball game.

MJ: Would she go to games with you when you were younger?

Barnicle: No. We didn’t have a lot of money. And it was a huge treat. And I assume, looking back on it, that a few economic tricks took place for us to be able to go to a ball game.

MJ: When you were younger, how many games would you be able to see in a season?

Barnicle: I didn’t go to that many when I was that young. But I was also lucky in that my uncle played major league baseball for the then-Boston Braves (now the Atlanta Braves), and he was a pitcher for the Boston Braves. And so growing up, my cousins and I had an entrée into that world that very few kids did. By the time I was 12 or 13, and given the ease of access to get to the games and the fact that they weren’t selling out, we went to a lot of games. And a lot of the guys that he played with, they were coaches on major league teams.

MJ: When did you start bringing your own kids to Fenway? Did you want them to be massive Sox fans at a young age?

Barnicle: Here’s the deal on that. I would take our two oldest boys to games from the time that they were five and six. And I would take them, first of all, because I was in charge of taking care of them on a particular day, so I’d take them to the ball park. And we would sit upstairs. And I never took them with the idea that I’m going to inculcate them. I don’t think you can do that. They are either going to like it or not like it, but I wasn’t going to force it on them. And luckily for me, they not only liked it, but loved it. They played it at a very high level throughout their young lives and still play it. They play hardball in a hardball league in the Bronx. One of them played a year of minor league baseball. They both played college baseball. And they do film stuff now, they have a production company for ESPN’s “Baseball Tonight.”

BY MIKE BARNICLE

It was nearly dusk, the weak winter sun finally surrendering for the day, and Kevin White was leaning against the brass rail that stood in front of a wide glass wall as he looked at the view from the mayor’s office, down toward Faneuil Hall and Quincy Market. It was close to Christmas and people below walked through oatmeal-colored slush to shops that glittered in the approaching grey of late afternoon.

Look at it, “ Kevin White was saying then. “Look at all the people down there. Ten years ago the place looked like a stable. Now it’s a palace.”

A thief called time has stolen more than three decades since he stood at that window. And a vicious illness called Alzheimer’s robbed him of memory, slowly pick-pocketing what he knew and loved about his family, his friends, the substance of his days, his accomplishments, his election wins and losses, his pride in appearance and, finally, his life.

Remarkable urban fact and extraordinary political reality: Kevin White was one of only four mayors to govern Boston across the last 50 years. Half a century: Four men!

He arrived at the old city hall on School Street, having defeated Louise Day Hicks who knew where she stood on race and schools and busing in the fall of 1967 after a bruising campaign that held the outline of a fire that would nearly consume the town seven years later. He had been Massachusetts Secretary of State since 1960 and he was an odd element added to the tribal politics that then dominated Boston.

Kevin White was always more Ivy League than Park League. He felt more at home in Harvard Yard than he did at The Stockyard. He was Beacon Hill more than he was Mission Hill. He knew all about Brooks Brothers and not much at all about the Bulger Brothers. He read history rather than precinct returns. He was neither a glad-hander or a back-slapper and other than his wife, his family, a few close friends like Bob Crane, the former Treasurer, and a couple others involved in politics, he had a distance about him that kept him from succumbing to the two items that have proven to be a death sentence to so many others around Boston: Resentment and envy. White was a big-picture guy in the small-frame city of the mid-20th Century.

He enjoyed politics the way chronic moviegoers enjoy a good film: For the plot, the storyline and, most of all, the characters. His appreciation for the business of elections was borne in part through his father Joe who was on so many municipal payrolls when White was growing up that he had earned the nickname, “Snow White and The Seven Jobs.” And there was his father-in-law, “Mother” Galvin, who dominated politics in Charlestown and defined a mixed marriage as an Irish girl marrying an Italian.

The first time he met John F. Kennedy was on the tarmac at Logan Airport in October 1962 when the President of the United States came to speak at a Democratic State Committee dinner at the old Armory on Commonwealth Avenue, across from Braves Field, now all gone, replaced by gleaming new dorms and a Boston University athletic center.

White was running for re-election as Secretary of State. The statewide candidates were told they had a choice: They could meet the President at the airport or they could have their picture taken with him at the black-tie dinner that evening but they could not do both.

“When he came down the steps of Air Force One, it was like the Sun-King had arrived, “White once recalled. “And then when he said what he said to Eddie McLaughlin I realized how different he was from anyone I had ever met before.”

The late Edward McLaughlin was then Lt. Governor of Massachusetts and he was first in line to greet Kennedy. And, unlike White and the other statewide candidates there, he wore a tuxedo. He was going to get his picture taken twice.

“I will always remember the twinkle in Kennedy’s eye when he saw Eddie in the tux, “Kevin White remembered. “He touched Eddie’s lapel and said, “Eddie, taking the job kind of seriously aren’t you?’ God that was funny.”

Through four city-wide elections, two of them – in 1975 and 1979 – knock down, hand-to-hand combat with former State Senator Joe Timilty and the searing, bleeding open wound that was busing, White’s ambition for any higher office diminished and disappeared, replaced by a desire to grow the city from a place of narrow streets and even narrower vision into a wider arena where people would come, go to school and stay; where development would flourish and provide a new coat of paint for a tired relic of a town that had a death rattle to it in the early 1970’s; he wanted to put his little big town on a larger stage for the world to see.

Kevin White was unafraid of talent, a big asset in attracting those who turned ideas like Quincy Market, Little City Hall, Summerthing and Tall Ships into a reality that helped the city grow up rather than simply grow older. Downtown began to flourish at the same time different neighborhoods retreated into a type of municipal paranoia, a kind of virus that spread block by block, transmitted by a near-fatal mixture of political incompetence, cynicism, racial tension, class conflict and inferior schools where – no matter where buses dropped off students – the ultimate destination for too many kids was a dead end when it came to a great education and a better life.

Those years, Judge Garrity’s ruling, blood in the streets, two campaigns against Timilty, the increasing self-imposed isolation within the Parkman House, exhausted White but he never surrendered to bitterness.

No mayor of Boston before or since has had to deal with the tumult, the division, the demands of a federal court, the need for the city to grow or die, the ingrained cynicism and the perpetual parochialism that has been as much a part of our lives around here as air. Kevin White did it, with more wins than losses.

If you are new to town or if you have never left, look around this morning as you drive to work, go to lunch, walk the dog, wait at a bus stop, emerge from Park Street Under, run along the Charles. There is no need to read any obituary of Kevin H. White. You are looking at it. You are part of it. It’s called Boston in the 21st Century.

He is one of 70 from Iowa killed in Iraq or Afghanistan fighting two wars that have had so few serving for so long as America plods into the second decade of a new century, exhausted and isolated from battles that crush the families of the fallen at home.

“I was just looking at a picture of Tommy and his older brother Joe,” Mary Ellen Ward was saying the other day. “It was taken on Oct. 31, 1987.

“He would have been about five years old. His brother was seven. A Halloween picture. Joe was dressed as a Ninja. Tom was in camouflage. He always wanted to be a Marine.

“The last time I talked to him was Christmas Day, a few days before he was killed. He was going to play flag football in the sand. He was on his second tour.”

“How old was he,” his mother was asked.

“Twenty-two,” she answered. “He was only 22.”

“It’s funny,” she was saying, “but the last time he was home, just before he left for his second tour of Iraq, we went shopping, just the two of us. And I had this feeling, this strange feeling, that I’m never going to see him again. I knew…I just knew.”

Across Iowa, the candidates appear in cities and towns like fast-moving clouds pushed across the flat landscape on a wind of ambition. Here is a Gingrich, then a Romney, a Santorum, a Paul, a Bachmann or Perry smiling, glad-handing, promoting, promising, pleading to be sent forward to New Hampshire and beyond by the handful of Iowans who will show up at caucuses Tuesday night.

“I don’t have much interest in it, politics,” said Mary Ellen Ward, who works for the state Child Support Recovery Unit. “And I kind of hate to say this but I think we ought to get everybody out of there, out of Congress. Why does it cost so much to run? I don’t understand that. Why do they get free health care, better health care than the rest of us do, for nothing? They get a nice pension too. They shouldn’t be serving more than two terms either. And none of them talk about the wars. It’s like it’s not there to them.”

She lives with her husband Larry in a city framed by the mythic elements of the country’s history. Council Bluffs sits at the edge of the great Missouri River, separated from Omaha, Neb., by waters that divide two states and dominate the landscape. It was once a huge railroad center when America moved mostly by train, before the automobile, the interstates, long after Lewis and Clark came through on the way to the Pacific.

The town, like most, has a narrative to it, a story that is both parochial and universal: It was built by pioneers who suffered and prospered yet greeted each sunrise with a sense of optimism.

Now, in a country confronted with and confused by political people, including an incumbent, all submitting a job application for the position of president of the United States, anxiety about the immediate future fills the air. The economy has flat-lined for three years. Washington is totally isolated from the rhythms, the mood, the fears and apprehension felt by most Americans. And the wars drag on, touching only the few who serve and their families who remain here, praying nobody knocks on the door at night to tell them a sniper, an IED, an ambush or a fire-fight has claimed a son, husband, daughter or dad.

So on Jan. 3, 2012, as candidates organize and hope for a finish that will fuel a continued campaign, Mary Ellen Ward will again – and daily – think of her son Tommy: Sgt. Thomas E. Houser, USMC, 2nd Force Reconnaissance Company, First Marine Division, killed on this day in 2005 in Iraq.

And she will barely notice the passing parade of politics because she has other concerns, another worry, one more mother’s burden: Her oldest boy, Joe, is scheduled to depart with the Marines in two months. For Afghanistan. For another tour in a war that has made much of our nation weary and too many of our politicians silent.

Mike Barnicle is an award-winning print and broadcast journalist and regular on MSNBC’s “Morning Joe”.

Deadline Artists: America’s Greatest Newspaper Columns

Edited by John Avlon, Jesse Angelo & Errol Louis

At a time of great transition in the news media, Deadline Artists celebrates the relevance of the newspaper column through the simple power of excellent writing. It is an inspiration for a new generation of writers—whether their medium is print or digital-looking to learn from the best of their predecessors.

This new book features two of Mike’s columns from The Boston Globe. The book says, “Barnicle is to Boston what Royko was to Chicago and Breslin is to New York—an authentic voice who comes to symbolize a great city. Almost a generation younger than Breslin & Co., Barnicle also serves as the keeper of the flame of the reported column. A speechwriter after college, Barnicle’s column with The Boston Globe ran from 1973 to 1998. He has subsequently written for the New York Daily News and the Boston Herald, logging an estimated four thousand columns in the process. He is also a frequent guest on MSNBC’s Morning Joe as well as a featured interview in Ken Burns’s Baseball: The Tenth Inning documentary.”

Read the columns here (you can buy the book by clicking here)

“Steak Tips to Die For” – Boston Globe – November 7, 1995

Those who think red meat might be bad for you have a pretty good argument this morning in the form of five dead guys killed yesterday at the 99 Restaurant in Charlestown. It appears that that two late Luisis, Bobby, the father, and Roman, his son, along with their three pals, sure did love it because there was so much beef spread out in front of the five victims that their table-top resembled a cattle drive.

“All that was missing was the marinara,” a detective was saying yesterday. “If they had linguini and marinara it would have been like that scene in The Godfather where Michael Corleone shoots the Mafia guy and the cop. But it was steak tips.”

Prior to stopping for a quick bite, Roman Luisi was on kind of a roll. According to police, he recently beat a double-murder charge in California. Where else?

But that was then and this is now. And Sunday night, he got in a fight in the North End. Supposedly, one of those he fought with was Damian Clemente, 20 years old and built like a steamer trunk. Clemente, quite capable of holding a grudge, is reliably reported to have sat on Luisi.

Plus, it is now alleged that at lunch yesterday, young Clemente, along with Vincent Perez, 27, walked into the crowded restaurant and began firing at five guys in between salads and entrée. The 99 is a popular establishment located at the edge of Charlestown, a section of the city often pointed to as a place where nearly everyone acts like Marcel Marceau after murders take place in plain view of hundreds.

Therefore, most locals were quick to point out that all allegedly involved in the shooting—the five slumped on the floor as well as the two morons quickly captured outside—were from across the bridge. Both the alleged shooters and the five victims hung out in the North End.

However, yesterday, it appears, everyone was playing an away game. For those who still think “The Mob” is an example of a talented organization capable of skillfully executing its game plan, there can be only deep disappointment in the aftermath of such horrendous, noisy and public violence.

It took, oh, about 45 seconds for authorities to track down Clemente and Perez. Clemente is of such proportions that his foot speed is minimal. And it is thought that his partner Perez’s thinking capacity is even slower than Clemente’s feet.

Two Everett policeman out of uniform—Bob Hall and Paul Durant—were having lunch a few feet away from where both Luisis and the others were having the last supper. The two cops have less than five years’ experience combined but both came up huge.

“They didn’t try anything crazy inside. They didn’t panic,” another detective pointed out last night. “They followed the two shooters out the door, put them down and held them there. They were unbelievably level-headed, even when two Boston cops arrived and had their guns drawn on the Everett cops because they didn’t know who they were, both guys stayed cool and identified themselves. And they are going to make two truly outstanding witnesses.”

The two Boston policemen who arrived in the parking lot where Clemente and Perez were prone on the asphalt were Tom Hennessey and Stephen Green. They were working a paid detail nearby which, all things being equal, immediately led one official to cast the event in its proper, parochial perspective: “This ought to put an end to the argument to do away with paid details,” he said. “Hey, ask yourself this question: You think a flagman could have arrested these guys?”

The entire event—perhaps four minutes in duration, involving at least 13 shots, five victims and two suspects caught—is a bitter example of how downsizing has affected even organized crime. For several years, the federal government has enforced mandatory retirement rules—called jail—on several top local mob executives.

What’s left are clowns who arrive for a great matinee murder in a beat-up blue Cadillac and a white Chrysler that look like they are used for Bumper-Car. The shooters then proceed to leave a restaurant filled with the smell of cordite and about 37 people capable of picking them out of a lineup.

“Part of it was kind of like in the movies, but part of it wasn’t,” an eyewitness said last night. “The shooting part was like you see in a movie but the fat guy almost slipped and fell when he was getting away. That part you don’t see in a movie. But what a mess that table was.”

“We have a lot of evidence, witnesses and even a couple weapons,” a detective pointed out last evening. “But the way things are going in this country it would not surprise me if the defense argues that they guys were killed by cholesterol.”

“New Land, Sad Story” – Boston Globe – November 23, 1995

Three Cadillac hearses were parked on Hastings Street outside Calvary Baptist Church in Lowell Tuesday morning as an old town wrestled with new grief. Inside, the caskets had been placed together by the altar while the mother of the dead boys, a Cambodian woman named Chhong Yim, wept so much it seemed she cried for a whole city.

The funeral occurred two days before the best of American holidays and revolved around a people, many of whom have felt on occasion that God is symbolized by stars, stripes and the freedom to walk without fear. But a bitter truth was being buried here as well because now every Cambodian man, woman and child knows that despite fleeing the Khmer Rouge and soldiers who killed on whim, nobody can run forever from a plague that is as much a bitter part of this young country as white meat and cranberry sauce.

The dead children were Visal Men, 15, along with his two brothers Virak, 14, and Sovanna, 9, born in the U.S.A. They were shot and stabbed last week when the mother’s friend, Vuthy Seng, allegedly became enraged at being spurned by Chhong Yim, who chose her children over Seng.

There sure are enough sad stories to go around on any given day. However, there aren’t many to equal the slow demise of a proud, gentle culture—Cambodian—as it is bastardized by the clutter and chaos we not only allow to occur but willingly accept as a cost of democracy.

The three boys died slowly; first one, then the other in a hospital and, finally, the third a few days after Seng supposedly had charged into the apartment with a gun and a machete. He shot and hacked all three children along with their sister, Sathy Men, who is 13 and stood bewildered beside her howling mother, the two of them survivors of a horror so deep their lives are forever maligned.

At 10:45, as the funeral was set to begin, two cops on motorcycles came up Hastings ahead of a bus filled with children from Butler Middle School. The boys and girls walked in silence into the chapel to pray for the dead who have left a firm imprint on their adopted hometown.

The crowd of mourners was thrilling in its diversity. There were policemen, firefighters, teachers and shopkeepers. The young knelt shoulder-to-shoulder with the old. There were Catholic nuns and Buddhist priests. There were friends of the family as well as total strangers summoned only by tragedy.

A little after 11 a.m., Hak Sen, who drove from Rhode Island, parked his car by the post office and headed toward Calvary Baptist Church.

“I am late. I got lost,” Hak Sen said.

“Are you a friend of the family?” he was asked.

“No,” he replied. “I do not know them. I come out of respect and sadness. We all make a terrible journey to come here to America and this is very, very bad.”

Hak Sen said he and his family were from Battambang Province, along the Thai-Cambodian border. He said that he served in the army before Pol Pot took over his country and that he and his family were forced to flee but not all made it to the refugee camps.

“I am lucky man,” Hak Sen pointed out. “I survive. My wife, she survive and two of our children, they survive.”

“Did you lose any children?” he was asked.

“Yes,” he said. “I lost three boys, just like this woman. Three boys and our daughter. They all dead. The malaria killed them in the jungle. There was not enough food and no water and they were young and could not fight the disease and they died. They all dead. My mother and father too.”

The innocent children inside the church as well as the big-hearted citizens of Lowell along with the majority of people who will buy a paper or carve a turkey today simply have no idea of the epic, tragic struggle of the Cambodians. They left a country where they were killed for owning a ballpoint pen or wearing a pair of eyeglasses to arrive in this country where, each day, we become more and more narcoticized by the scale of violence around us.

At the conclusion of the service, Lowell detectives Mike Durkin, John Boutselis and Phil Conroy helped carry the caskets to the hearses. The procession wound slowly through city streets, pausing for a few seconds outside the Butler School, where pupils lined both sides of the road like grieving sentries as the entourage entered Westlawn Cemetery.

“This is as sad as it gets,” said Roger LaPointe, a cemetery worker. “We cut the first two graves the end of last week but the funeral director told us we better hold on. When the third boy died, we had to cut it some more. It’s an awful thing. That hole just kept getting bigger.”

With husband Bob, Myra Kraft attended many fund-raisers, smiling and greeting donors. (1997 File/The Boston Globe) |

She was the conscience and soul of the Patriots, a woman who came to football reluctantly, through marriage, then used the currency of football fame to enhance her lifelong missions of fund-raising and philanthropy.

“Without Myra Kraft, it’s quite possible we’d be going to Hartford to watch the Patriots,’’ former Globe columnist Mike Barnicle said yesterday after it was announced that Myra succumbed to cancer at the age of 68. “Obviously, Bob Kraft has deeps roots in this area, but Myra was so much a part of this community – the larger community beyond the sports world – she was never going to allow her husband to leave.’’

We all knew Myra was failing in recent years, but she never wanted it to be about herself. Through the decades, thousands of patients were treated at the Kraft Family Blood Donor Center at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, but when Myra got cancer there was no announcement; instead, the Krafts announced a $20 million gift to Partners HealthCare to create the Kraft Family National Center for Leadership and Training in Community Health.

It was always that way. You’d go to a fund-raiser and Myra would be standing off to the side with Bob, smiling, greeting donors, and gently pushing the cause of the Greater Good. They were married for 48 years and had four sons who learned from their mom that more is expected of those to whom more is given.

It’s fashionable to enlarge the deeds of the dead and make them greater than they were in real life. This would be impossible with Myra Kraft. She was the real deal. Myra Hiatt Kraft was a Worcester girl, a child of privilege, and she spent her life giving back to her community.

Not a sports fan at heart, Myra was a quick study when Bob bought the team in 1994. Sitting next to Bob and eldest son Jonathan, she learned what she needed to know about football. When something wasn’t right, she spoke up. Myra disapproved when the Patriots drafted sex offender Christian Peter in 1996. Peter was quickly cut. She objected publicly when Bill Parcells referred to Terry Glenn as “she.’’ Like Parcells and Pete Carroll before him, Bill Belichick operated with the knowledge that Myra was watching. Keep the bad boys away from Foxborough. Don’t sell your soul in the pursuit of championships.

The base of Myra’s philanthropic works was the Robert K. and Myra H. Kraft Family Foundation. The Boys & Girls Clubs of Boston were a particular passion. Among its other missions, the Kraft Foundation endowed chairs and built buildings at Brandeis, Columbia, Harvard, BC, and Holy Cross.

BC and HC are Jesuit institutions. Myra Kraft was Jewish and worked tirelessly for Jewish and Israeli charities, but that didn’t stop her from helping local Catholic colleges.

“She was the daughter of Jack [Jacob] and Frances Hiatt,’’ Father John Brooks, the former president of Holy Cross, recalled. “Jack was a great benefactor of Holy Cross. He was on our board and was a very important person to the city of Worcester. I was a regular attendee of the annual Passover dinner at the Hiatt home when Myra was still living in Worcester. What struck me about Myra was that she was very proud and was a wonderful mother to her four boys.’’

During the 2010 season, Myra steered the New England Patriots Charitable Foundation toward early detection of cancer. Partnering with three local hospitals, the Krafts and the Patriots promoted the “Kick Cancer’’ campaign, never mentioning Myra’s struggle with the disease.

Anne Finucane, Bank of America’s Northeast president, held a large Cure For Epilepsy dinner at the Museum of Fine Arts last October and recalled, “Myra showed up at our event even though she was battling her illness and they were in the middle of their season. That’s the way she was. She could come and see you and make a pitch on behalf of an organization. There are people who just lend their name and then there are people who take a leadership role to advance an issue. She was a pretty good inspiration for anyone in this city.’’

Just as it’s hard to imagine the Patriots without Bob Kraft, it’s impossible to imagine Bob without Myra. After every game, home or away, win or lose, Myra was at Bob’s side, waiting at the end of the tunnel outside the Patriots locker room.

We miss her already.

Dan Shaughnessy is a Globe columnist.

Globe Columnist

July 20, 2011

Next time you feel like ripping Terry Francona, try to remember that the man has a lot on his mind. The manager’s son, Nick Francona, a former pitcher at the University of Pennsylvania, is a lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps, serving a six-month tour, leading a rifle platoon in Afghanistan. Twenty-six-year-old Nick is one of the more impressive young men you’ll ever meet. In a terrific piece for Grantland.com, Mike Barnicle asked Terry Francona how’s he doing as the dad of one of our soldiers at war. “I’m doing awful,’’ answered the manager. “My wife’s doing worse. I think about it all the time. Worry about it all the time. Hard not to. Try and stay away from the news about it. Try not to watch TV when stories about it are on, but it’s there, you know? It’s always there.’’

Mar. 1, 2011

BOSTON — The Harvard community — and people the world over — is mourning the death of Reverend Peter Gomes, the man who ran the university’s Memorial Church for over forty years.

Gomes died Monday night because of complications from a stroke he had in December. He was 68.

|

| The Reverend Peter Gomes died Monday at the age of 68, after a more-than 40-year ministry at Harvard University. |

Gomes’ longtime friend, writer and columnist Mike Barnicle, met Gomes because the two would regularly spend early mornings at the same restaurant. “He was an education to sit with, next to, to listen to, a sheer education. Not just in terms of his moral values but his view on the world,” Barnicle told WGBH’s Emily Rooney on Tuesday.

A black, openly gay minister, Gomes was a decided rarity. He came out about his sexuality in 1991.

He was also politically conservative for most of his career, although he changed his political affiliation to Democrat to vote for Gov. Deval Patrick in 2006.

Barnicle said Gomes learned from his own experience being different, and set out to help others with theirs.

“He was was an expert at honing in on the demonization of people,” Barnicle said. “He could see people and institutions being demonized well before it would become apparent tthat they were being demonized.”

That, Barnicle said, gave Gomes a sense of fairness that underguarded his political and religious beliefs.

“It’s not fair to go after people because of who they are, or because of their sexual orientation, or because of their color, or because of their income, or because of their zip code. That’s who he was, he was an expert in what’s fair,” Barnicle said.

Gomes was known for his soaring, intricate speaking style. “I like playing with words and structure,” he said once, “Marching up to an idea, saluting, backing off, making a feint and then turning around.”

“His sermons were actually high theater in my mind,” Barnicle remembered.

Gomes did not leave behind a memoir; He said he’d start work on it when he retired, at 70. It’s a shame, Barnicle said. “We need more of him than just a memoir, we need people like him every day.”

Gomes reflected on his life’s work — and his death — on Charlie Rose’s talk show in 2007.

I even have the tombstone the verse on my stone is to be from 2 Timothy. “Study to show thyself approved unto God a workman who needeth not to be ashamed, rightly dividing the word of truth.” That’s what I try to do, that’s what I want people to thnk of me after I’m gone. When I was young, we all had to memorize vast quantities of scripture and I remember that passage from Timothy I thought, ‘Hey that’s not a bad life’s work.’ And in a way I’ve tried to live into it. So my epitaph is not going to be new to me, it’s the path I have followed in my ministry and my life.

Mike Barnicle talks about the baseball gloves he’s had since 1954. “The Tenth Inning,” is a two-part, four-hour documentary film directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick that premieres this week, September 28 & 29th at 8pm ET on PBS. A new chapter in Burns’s landmark 1994 series, “Baseball,” “The Tenth Inning” tells the tumultuous story of the national pastime from the 1990s to the present day.

Mark Feeney from the Boston Globe says, “Mike Barnicle, who toiled for many years at this newspaper, serves as representative of Red Sox Nation. One of his great strengths on both page and screen has always been what a potent and vivid presence he has.”

Mike Barnicle talks about the Red Sox loss of 2003 to the Yankees and how it impacted his son, Tim. “The Tenth Inning,” is a two-part, four-hour documentary film directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick that premieres this week, September 28 & 29th at 8pm ET on PBS. A new chapter in Burns’s landmark 1994 series, “Baseball,” “The Tenth Inning” tells the tumultuous story of the national pastime from the 1990s to the present day.

David Barron of the Houston Chronicle calls Barnicle’s contribution to the film “perhaps the most valuable addition… (Barnicle) provokes simultaneous laughter and tears on the burden of passing his love of the Red Sox to a second generation….”

“The tale of the Sox bookend years of failure and triumph are given a personal connective thread by former Globe columnist Mike Barnicle, who frames the story through the eyes of his children and his late mother, who, Barnicle recalls, used to sit on a porch in Fitchburg, Mass., her nylons rolled down, listening to the Sox on the radio and keeping score on a sheet of paper.” — Gordon Edes for ESPN.com

Watch here: https://video.pbs.org/video/1596452376/#

Sunday, Jan. 17, 2010

In Massachusetts, Scott Brown Rides a Political Perfect Storm

By MIKE BARNICLE

Scott Brown, wearing a dark suit, blue shirt and red stripe tie in the mild winter air, stood a few yards in front of a statue of Paul Revere and directly across the street from St. Stephen’s Church, where Rose Kennedy’s funeral Mass was celebrated in 1995, telling about 200 gleeful voters that they had a chance to rearrange a political universe. The crowd spilled across the sidewalk onto the narrow street that cuts through the heart of the city’s North End, the local cannoli capital, located in Ward 3 that Barack Obama carried 2 to 1 just 15 months ago.

” ‘Scuse me,” Joanne Prevost said to a man who had two “Scott Brown for Senate” signs tucked under his left arm. “Can I have one of those signs? I’ll put it in my window. My office is right there.”

She turned and pointed across the street to a storefront with the words ‘Anzalone Realty’ stenciled on window. “Everybody will see it.” (See the top 10 political defections.)

Read the rest of the article at: https://www.time.com/time/politics/article/0,8599,1954366,00.html?xid=rss-topstories

Wednesday, December 9, 2009

The Afghan War Through a Marine Mother’s Eyes

By Mike Barnicle

Nearly everything is a sad a sad reminder for Mélida Arredondo: the news on TV, stories in the paper, speeches of Barack Obama and others who talk about a war that seems to have lasted so long and affected so many lives, those lost as well as those left behind.

“Did your son like the Marine Corps?” I ask her.

“Yes,” she replies. “He loved it.”

“And why did he join?”

“Too poor to go to college,” Mélida Arredondo says.

Alexander Arredondo enlisted at 17 and was killed at 20 in Najaf during his second deployment in Iraq. He died on his father’s birthday, Aug. 25, 2004, when Carlos Arredondo turned 44.

“My husband almost killed himself in grief,” his wife says. “The day [the Marines] came to tell us Alex was dead, he poured gasoline all over himself and all over the inside of [their] car and lit it on fire. He survived … physically.”

Read the rest of Mike’s column at Time.com

Hotline On Call/National Journal

By Rachelle Douillard-Prouix

During this morning’s broadcast of “Morning Joe,” MSNBC’s Willie Geist had a (lighthearted) bone to pick with Mike Barnicle over sarcastic comments the latter made during the show’s Wednesday broadcast. To highlight the annual lighting of the Christmas tree in Rockefeller Center that took place last night, Geist reported live from the courtyard.

Barnicle, following Geist’s report from in front of the hulking tree: “I finally realized what I want for Christmas, Willie. I would like to see that tree fall right on you right now.”

Geist reported this morning on the show that he had received many emails regarding Barnicle’s comments, and demanded an apology.

Geist: “He said he wanted the tree to fall on me. I’ve received a number of emails, including from members of my own family, attacking Mike Barnicle.

Mike Barnicle, what say you, sir?”

Barnicle, reading from newspaper coverage of the statement golfer Tiger Woods released in light of his own recent controversy: “Willie, and all of you people out there, let me just say, I have let my family down, and I regret those transgressions with all my heart. I have not been true to my values in that statement yesterday.”

Continued Barnicle: “And I’m far short of perfect. I am dealing with my behavior, and personal failings, behind closed doors with Willie and my family. So, I beg your forgiveness.”

Geist: “I forgive you for your personal failings. Thank you, Mike Barnicle. Apology accepted.”

*NEW* True Compass: The Life of Senator Edward M. Kennedy

THURSDAY, DECEMBER 3, 2009 6:00-7:30 PM

Victoria Reggie Kennedy introduces historians Doris Kearns Goodwin, Michael Beschloss and Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne, who will discuss Senator Kennedy’s memoir, True Compass, his role in history and his legacy with political analyst, Mike Barnicle.

Seating is limited, first come, first served.

Friday, Oct. 16, 2009

Last week, Laura and Gary Sklaver buried their oldest boy, Ben, who was 32 when killed by a suicide bomber in the remote village of Murcheh in the distant land of Afghanistan. Ben was a captain in the United States Army. Now he has become one of 804 Americans, 37 from Connecticut, to lose their lives in an expanding war that belongs mostly to the parents and families of those who serve a nation preoccupied by a wounded economy and political polarization.

“He didn’t have to go,” Laura Sklaver said the other day. “His obligation was up in May.”

“But he was recalled in March,” Gary Sklaver added. “And he didn’t want to leave his men.”

Ben Sklaver grew up drawn to service. He admired his grandfather who served with Patton’s Army in World War II. He joined ROTC at Tufts, received a Master’s in international relations from the Fletcher School of Diplomacy, was commissioned as an officer in the Army Reserve in 2003 and became convinced that a world consumed with conflict and terror might be changed by Americans bringing clean water, medicine and food as much as by drones, missiles and military might.

09/18/09: Barnicle talks about Jared Monti receiving the Medal of Honor yesterday.

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/09/18/91809-jared-montimedal-of-honor.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

Mike Barnicle is a veteran print and broadcast journalist recognized for his street-smart, straightforward style honed over nearly four decades in the field. The Massachusetts native has written 4,000-plus columns collectively for The Boston Globe, Boston Herald and the New York Daily News, and continues to champion the struggles and triumphs of the every man by giving voice to the essential stories of today on television, radio, and in print.