With husband Bob, Myra Kraft attended many fund-raisers, smiling and greeting donors. (1997 File/The Boston Globe) |

BY MIKE BARNICLE

It was nearly dusk, the weak winter sun finally surrendering for the day, and Kevin White was leaning against the brass rail that stood in front of a wide glass wall as he looked at the view from the mayor’s office, down toward Faneuil Hall and Quincy Market. It was close to Christmas and people below walked through oatmeal-colored slush to shops that glittered in the approaching grey of late afternoon.

Look at it, “ Kevin White was saying then. “Look at all the people down there. Ten years ago the place looked like a stable. Now it’s a palace.”

A thief called time has stolen more than three decades since he stood at that window. And a vicious illness called Alzheimer’s robbed him of memory, slowly pick-pocketing what he knew and loved about his family, his friends, the substance of his days, his accomplishments, his election wins and losses, his pride in appearance and, finally, his life.

Remarkable urban fact and extraordinary political reality: Kevin White was one of only four mayors to govern Boston across the last 50 years. Half a century: Four men!

He arrived at the old city hall on School Street, having defeated Louise Day Hicks who knew where she stood on race and schools and busing in the fall of 1967 after a bruising campaign that held the outline of a fire that would nearly consume the town seven years later. He had been Massachusetts Secretary of State since 1960 and he was an odd element added to the tribal politics that then dominated Boston.

Kevin White was always more Ivy League than Park League. He felt more at home in Harvard Yard than he did at The Stockyard. He was Beacon Hill more than he was Mission Hill. He knew all about Brooks Brothers and not much at all about the Bulger Brothers. He read history rather than precinct returns. He was neither a glad-hander or a back-slapper and other than his wife, his family, a few close friends like Bob Crane, the former Treasurer, and a couple others involved in politics, he had a distance about him that kept him from succumbing to the two items that have proven to be a death sentence to so many others around Boston: Resentment and envy. White was a big-picture guy in the small-frame city of the mid-20th Century.

He enjoyed politics the way chronic moviegoers enjoy a good film: For the plot, the storyline and, most of all, the characters. His appreciation for the business of elections was borne in part through his father Joe who was on so many municipal payrolls when White was growing up that he had earned the nickname, “Snow White and The Seven Jobs.” And there was his father-in-law, “Mother” Galvin, who dominated politics in Charlestown and defined a mixed marriage as an Irish girl marrying an Italian.

The first time he met John F. Kennedy was on the tarmac at Logan Airport in October 1962 when the President of the United States came to speak at a Democratic State Committee dinner at the old Armory on Commonwealth Avenue, across from Braves Field, now all gone, replaced by gleaming new dorms and a Boston University athletic center.

White was running for re-election as Secretary of State. The statewide candidates were told they had a choice: They could meet the President at the airport or they could have their picture taken with him at the black-tie dinner that evening but they could not do both.

“When he came down the steps of Air Force One, it was like the Sun-King had arrived, “White once recalled. “And then when he said what he said to Eddie McLaughlin I realized how different he was from anyone I had ever met before.”

The late Edward McLaughlin was then Lt. Governor of Massachusetts and he was first in line to greet Kennedy. And, unlike White and the other statewide candidates there, he wore a tuxedo. He was going to get his picture taken twice.

“I will always remember the twinkle in Kennedy’s eye when he saw Eddie in the tux, “Kevin White remembered. “He touched Eddie’s lapel and said, “Eddie, taking the job kind of seriously aren’t you?’ God that was funny.”

Through four city-wide elections, two of them – in 1975 and 1979 – knock down, hand-to-hand combat with former State Senator Joe Timilty and the searing, bleeding open wound that was busing, White’s ambition for any higher office diminished and disappeared, replaced by a desire to grow the city from a place of narrow streets and even narrower vision into a wider arena where people would come, go to school and stay; where development would flourish and provide a new coat of paint for a tired relic of a town that had a death rattle to it in the early 1970’s; he wanted to put his little big town on a larger stage for the world to see.

Kevin White was unafraid of talent, a big asset in attracting those who turned ideas like Quincy Market, Little City Hall, Summerthing and Tall Ships into a reality that helped the city grow up rather than simply grow older. Downtown began to flourish at the same time different neighborhoods retreated into a type of municipal paranoia, a kind of virus that spread block by block, transmitted by a near-fatal mixture of political incompetence, cynicism, racial tension, class conflict and inferior schools where – no matter where buses dropped off students – the ultimate destination for too many kids was a dead end when it came to a great education and a better life.

Those years, Judge Garrity’s ruling, blood in the streets, two campaigns against Timilty, the increasing self-imposed isolation within the Parkman House, exhausted White but he never surrendered to bitterness.

No mayor of Boston before or since has had to deal with the tumult, the division, the demands of a federal court, the need for the city to grow or die, the ingrained cynicism and the perpetual parochialism that has been as much a part of our lives around here as air. Kevin White did it, with more wins than losses.

If you are new to town or if you have never left, look around this morning as you drive to work, go to lunch, walk the dog, wait at a bus stop, emerge from Park Street Under, run along the Charles. There is no need to read any obituary of Kevin H. White. You are looking at it. You are part of it. It’s called Boston in the 21st Century.

He is one of 70 from Iowa killed in Iraq or Afghanistan fighting two wars that have had so few serving for so long as America plods into the second decade of a new century, exhausted and isolated from battles that crush the families of the fallen at home.

“I was just looking at a picture of Tommy and his older brother Joe,” Mary Ellen Ward was saying the other day. “It was taken on Oct. 31, 1987.

“He would have been about five years old. His brother was seven. A Halloween picture. Joe was dressed as a Ninja. Tom was in camouflage. He always wanted to be a Marine.

“The last time I talked to him was Christmas Day, a few days before he was killed. He was going to play flag football in the sand. He was on his second tour.”

“How old was he,” his mother was asked.

“Twenty-two,” she answered. “He was only 22.”

“It’s funny,” she was saying, “but the last time he was home, just before he left for his second tour of Iraq, we went shopping, just the two of us. And I had this feeling, this strange feeling, that I’m never going to see him again. I knew…I just knew.”

Across Iowa, the candidates appear in cities and towns like fast-moving clouds pushed across the flat landscape on a wind of ambition. Here is a Gingrich, then a Romney, a Santorum, a Paul, a Bachmann or Perry smiling, glad-handing, promoting, promising, pleading to be sent forward to New Hampshire and beyond by the handful of Iowans who will show up at caucuses Tuesday night.

“I don’t have much interest in it, politics,” said Mary Ellen Ward, who works for the state Child Support Recovery Unit. “And I kind of hate to say this but I think we ought to get everybody out of there, out of Congress. Why does it cost so much to run? I don’t understand that. Why do they get free health care, better health care than the rest of us do, for nothing? They get a nice pension too. They shouldn’t be serving more than two terms either. And none of them talk about the wars. It’s like it’s not there to them.”

She lives with her husband Larry in a city framed by the mythic elements of the country’s history. Council Bluffs sits at the edge of the great Missouri River, separated from Omaha, Neb., by waters that divide two states and dominate the landscape. It was once a huge railroad center when America moved mostly by train, before the automobile, the interstates, long after Lewis and Clark came through on the way to the Pacific.

The town, like most, has a narrative to it, a story that is both parochial and universal: It was built by pioneers who suffered and prospered yet greeted each sunrise with a sense of optimism.

Now, in a country confronted with and confused by political people, including an incumbent, all submitting a job application for the position of president of the United States, anxiety about the immediate future fills the air. The economy has flat-lined for three years. Washington is totally isolated from the rhythms, the mood, the fears and apprehension felt by most Americans. And the wars drag on, touching only the few who serve and their families who remain here, praying nobody knocks on the door at night to tell them a sniper, an IED, an ambush or a fire-fight has claimed a son, husband, daughter or dad.

So on Jan. 3, 2012, as candidates organize and hope for a finish that will fuel a continued campaign, Mary Ellen Ward will again – and daily – think of her son Tommy: Sgt. Thomas E. Houser, USMC, 2nd Force Reconnaissance Company, First Marine Division, killed on this day in 2005 in Iraq.

And she will barely notice the passing parade of politics because she has other concerns, another worry, one more mother’s burden: Her oldest boy, Joe, is scheduled to depart with the Marines in two months. For Afghanistan. For another tour in a war that has made much of our nation weary and too many of our politicians silent.

Mike Barnicle is an award-winning print and broadcast journalist and regular on MSNBC’s “Morning Joe”.

Deadline Artists: America’s Greatest Newspaper Columns

Edited by John Avlon, Jesse Angelo & Errol Louis

At a time of great transition in the news media, Deadline Artists celebrates the relevance of the newspaper column through the simple power of excellent writing. It is an inspiration for a new generation of writers—whether their medium is print or digital-looking to learn from the best of their predecessors.

This new book features two of Mike’s columns from The Boston Globe. The book says, “Barnicle is to Boston what Royko was to Chicago and Breslin is to New York—an authentic voice who comes to symbolize a great city. Almost a generation younger than Breslin & Co., Barnicle also serves as the keeper of the flame of the reported column. A speechwriter after college, Barnicle’s column with The Boston Globe ran from 1973 to 1998. He has subsequently written for the New York Daily News and the Boston Herald, logging an estimated four thousand columns in the process. He is also a frequent guest on MSNBC’s Morning Joe as well as a featured interview in Ken Burns’s Baseball: The Tenth Inning documentary.”

Read the columns here (you can buy the book by clicking here)

“Steak Tips to Die For” – Boston Globe – November 7, 1995

Those who think red meat might be bad for you have a pretty good argument this morning in the form of five dead guys killed yesterday at the 99 Restaurant in Charlestown. It appears that that two late Luisis, Bobby, the father, and Roman, his son, along with their three pals, sure did love it because there was so much beef spread out in front of the five victims that their table-top resembled a cattle drive.

“All that was missing was the marinara,” a detective was saying yesterday. “If they had linguini and marinara it would have been like that scene in The Godfather where Michael Corleone shoots the Mafia guy and the cop. But it was steak tips.”

Prior to stopping for a quick bite, Roman Luisi was on kind of a roll. According to police, he recently beat a double-murder charge in California. Where else?

But that was then and this is now. And Sunday night, he got in a fight in the North End. Supposedly, one of those he fought with was Damian Clemente, 20 years old and built like a steamer trunk. Clemente, quite capable of holding a grudge, is reliably reported to have sat on Luisi.

Plus, it is now alleged that at lunch yesterday, young Clemente, along with Vincent Perez, 27, walked into the crowded restaurant and began firing at five guys in between salads and entrée. The 99 is a popular establishment located at the edge of Charlestown, a section of the city often pointed to as a place where nearly everyone acts like Marcel Marceau after murders take place in plain view of hundreds.

Therefore, most locals were quick to point out that all allegedly involved in the shooting—the five slumped on the floor as well as the two morons quickly captured outside—were from across the bridge. Both the alleged shooters and the five victims hung out in the North End.

However, yesterday, it appears, everyone was playing an away game. For those who still think “The Mob” is an example of a talented organization capable of skillfully executing its game plan, there can be only deep disappointment in the aftermath of such horrendous, noisy and public violence.

It took, oh, about 45 seconds for authorities to track down Clemente and Perez. Clemente is of such proportions that his foot speed is minimal. And it is thought that his partner Perez’s thinking capacity is even slower than Clemente’s feet.

Two Everett policeman out of uniform—Bob Hall and Paul Durant—were having lunch a few feet away from where both Luisis and the others were having the last supper. The two cops have less than five years’ experience combined but both came up huge.

“They didn’t try anything crazy inside. They didn’t panic,” another detective pointed out last night. “They followed the two shooters out the door, put them down and held them there. They were unbelievably level-headed, even when two Boston cops arrived and had their guns drawn on the Everett cops because they didn’t know who they were, both guys stayed cool and identified themselves. And they are going to make two truly outstanding witnesses.”

The two Boston policemen who arrived in the parking lot where Clemente and Perez were prone on the asphalt were Tom Hennessey and Stephen Green. They were working a paid detail nearby which, all things being equal, immediately led one official to cast the event in its proper, parochial perspective: “This ought to put an end to the argument to do away with paid details,” he said. “Hey, ask yourself this question: You think a flagman could have arrested these guys?”

The entire event—perhaps four minutes in duration, involving at least 13 shots, five victims and two suspects caught—is a bitter example of how downsizing has affected even organized crime. For several years, the federal government has enforced mandatory retirement rules—called jail—on several top local mob executives.

What’s left are clowns who arrive for a great matinee murder in a beat-up blue Cadillac and a white Chrysler that look like they are used for Bumper-Car. The shooters then proceed to leave a restaurant filled with the smell of cordite and about 37 people capable of picking them out of a lineup.

“Part of it was kind of like in the movies, but part of it wasn’t,” an eyewitness said last night. “The shooting part was like you see in a movie but the fat guy almost slipped and fell when he was getting away. That part you don’t see in a movie. But what a mess that table was.”

“We have a lot of evidence, witnesses and even a couple weapons,” a detective pointed out last evening. “But the way things are going in this country it would not surprise me if the defense argues that they guys were killed by cholesterol.”

“New Land, Sad Story” – Boston Globe – November 23, 1995

Three Cadillac hearses were parked on Hastings Street outside Calvary Baptist Church in Lowell Tuesday morning as an old town wrestled with new grief. Inside, the caskets had been placed together by the altar while the mother of the dead boys, a Cambodian woman named Chhong Yim, wept so much it seemed she cried for a whole city.

The funeral occurred two days before the best of American holidays and revolved around a people, many of whom have felt on occasion that God is symbolized by stars, stripes and the freedom to walk without fear. But a bitter truth was being buried here as well because now every Cambodian man, woman and child knows that despite fleeing the Khmer Rouge and soldiers who killed on whim, nobody can run forever from a plague that is as much a bitter part of this young country as white meat and cranberry sauce.

The dead children were Visal Men, 15, along with his two brothers Virak, 14, and Sovanna, 9, born in the U.S.A. They were shot and stabbed last week when the mother’s friend, Vuthy Seng, allegedly became enraged at being spurned by Chhong Yim, who chose her children over Seng.

There sure are enough sad stories to go around on any given day. However, there aren’t many to equal the slow demise of a proud, gentle culture—Cambodian—as it is bastardized by the clutter and chaos we not only allow to occur but willingly accept as a cost of democracy.

The three boys died slowly; first one, then the other in a hospital and, finally, the third a few days after Seng supposedly had charged into the apartment with a gun and a machete. He shot and hacked all three children along with their sister, Sathy Men, who is 13 and stood bewildered beside her howling mother, the two of them survivors of a horror so deep their lives are forever maligned.

At 10:45, as the funeral was set to begin, two cops on motorcycles came up Hastings ahead of a bus filled with children from Butler Middle School. The boys and girls walked in silence into the chapel to pray for the dead who have left a firm imprint on their adopted hometown.

The crowd of mourners was thrilling in its diversity. There were policemen, firefighters, teachers and shopkeepers. The young knelt shoulder-to-shoulder with the old. There were Catholic nuns and Buddhist priests. There were friends of the family as well as total strangers summoned only by tragedy.

A little after 11 a.m., Hak Sen, who drove from Rhode Island, parked his car by the post office and headed toward Calvary Baptist Church.

“I am late. I got lost,” Hak Sen said.

“Are you a friend of the family?” he was asked.

“No,” he replied. “I do not know them. I come out of respect and sadness. We all make a terrible journey to come here to America and this is very, very bad.”

Hak Sen said he and his family were from Battambang Province, along the Thai-Cambodian border. He said that he served in the army before Pol Pot took over his country and that he and his family were forced to flee but not all made it to the refugee camps.

“I am lucky man,” Hak Sen pointed out. “I survive. My wife, she survive and two of our children, they survive.”

“Did you lose any children?” he was asked.

“Yes,” he said. “I lost three boys, just like this woman. Three boys and our daughter. They all dead. The malaria killed them in the jungle. There was not enough food and no water and they were young and could not fight the disease and they died. They all dead. My mother and father too.”

The innocent children inside the church as well as the big-hearted citizens of Lowell along with the majority of people who will buy a paper or carve a turkey today simply have no idea of the epic, tragic struggle of the Cambodians. They left a country where they were killed for owning a ballpoint pen or wearing a pair of eyeglasses to arrive in this country where, each day, we become more and more narcoticized by the scale of violence around us.

At the conclusion of the service, Lowell detectives Mike Durkin, John Boutselis and Phil Conroy helped carry the caskets to the hearses. The procession wound slowly through city streets, pausing for a few seconds outside the Butler School, where pupils lined both sides of the road like grieving sentries as the entourage entered Westlawn Cemetery.

“This is as sad as it gets,” said Roger LaPointe, a cemetery worker. “We cut the first two graves the end of last week but the funeral director told us we better hold on. When the third boy died, we had to cut it some more. It’s an awful thing. That hole just kept getting bigger.”

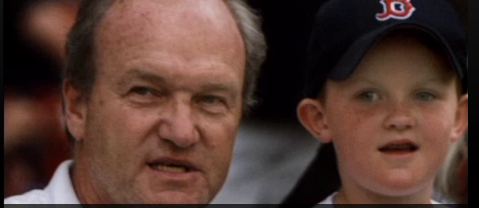

With husband Bob, Myra Kraft attended many fund-raisers, smiling and greeting donors. (1997 File/The Boston Globe) |

She was the conscience and soul of the Patriots, a woman who came to football reluctantly, through marriage, then used the currency of football fame to enhance her lifelong missions of fund-raising and philanthropy.

“Without Myra Kraft, it’s quite possible we’d be going to Hartford to watch the Patriots,’’ former Globe columnist Mike Barnicle said yesterday after it was announced that Myra succumbed to cancer at the age of 68. “Obviously, Bob Kraft has deeps roots in this area, but Myra was so much a part of this community – the larger community beyond the sports world – she was never going to allow her husband to leave.’’

We all knew Myra was failing in recent years, but she never wanted it to be about herself. Through the decades, thousands of patients were treated at the Kraft Family Blood Donor Center at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, but when Myra got cancer there was no announcement; instead, the Krafts announced a $20 million gift to Partners HealthCare to create the Kraft Family National Center for Leadership and Training in Community Health.

It was always that way. You’d go to a fund-raiser and Myra would be standing off to the side with Bob, smiling, greeting donors, and gently pushing the cause of the Greater Good. They were married for 48 years and had four sons who learned from their mom that more is expected of those to whom more is given.

It’s fashionable to enlarge the deeds of the dead and make them greater than they were in real life. This would be impossible with Myra Kraft. She was the real deal. Myra Hiatt Kraft was a Worcester girl, a child of privilege, and she spent her life giving back to her community.

Not a sports fan at heart, Myra was a quick study when Bob bought the team in 1994. Sitting next to Bob and eldest son Jonathan, she learned what she needed to know about football. When something wasn’t right, she spoke up. Myra disapproved when the Patriots drafted sex offender Christian Peter in 1996. Peter was quickly cut. She objected publicly when Bill Parcells referred to Terry Glenn as “she.’’ Like Parcells and Pete Carroll before him, Bill Belichick operated with the knowledge that Myra was watching. Keep the bad boys away from Foxborough. Don’t sell your soul in the pursuit of championships.

The base of Myra’s philanthropic works was the Robert K. and Myra H. Kraft Family Foundation. The Boys & Girls Clubs of Boston were a particular passion. Among its other missions, the Kraft Foundation endowed chairs and built buildings at Brandeis, Columbia, Harvard, BC, and Holy Cross.

BC and HC are Jesuit institutions. Myra Kraft was Jewish and worked tirelessly for Jewish and Israeli charities, but that didn’t stop her from helping local Catholic colleges.

“She was the daughter of Jack [Jacob] and Frances Hiatt,’’ Father John Brooks, the former president of Holy Cross, recalled. “Jack was a great benefactor of Holy Cross. He was on our board and was a very important person to the city of Worcester. I was a regular attendee of the annual Passover dinner at the Hiatt home when Myra was still living in Worcester. What struck me about Myra was that she was very proud and was a wonderful mother to her four boys.’’

During the 2010 season, Myra steered the New England Patriots Charitable Foundation toward early detection of cancer. Partnering with three local hospitals, the Krafts and the Patriots promoted the “Kick Cancer’’ campaign, never mentioning Myra’s struggle with the disease.

Anne Finucane, Bank of America’s Northeast president, held a large Cure For Epilepsy dinner at the Museum of Fine Arts last October and recalled, “Myra showed up at our event even though she was battling her illness and they were in the middle of their season. That’s the way she was. She could come and see you and make a pitch on behalf of an organization. There are people who just lend their name and then there are people who take a leadership role to advance an issue. She was a pretty good inspiration for anyone in this city.’’

Just as it’s hard to imagine the Patriots without Bob Kraft, it’s impossible to imagine Bob without Myra. After every game, home or away, win or lose, Myra was at Bob’s side, waiting at the end of the tunnel outside the Patriots locker room.

We miss her already.

Dan Shaughnessy is a Globe columnist.

Glaring Omission in Republican Debate: Why So Little Mention of Our Costly War?

By Mike Barnicle

Manchester, N.H. – At ten past eight Monday evening, Michele Bachmann decided to separate herself from the six guys next to her on the stage by telling John King of CNN why she had come to St. Anselm’s College. She did this on the fifth anniversary of a day when a young man from New Hampshire was killed in a war hardly mentioned last night.

“John…I just want to make an announcement,” she said as the first big TV debate among Republican candidates for president began, “I filed today my paperwork to seek the office of the presidency of the United States. . . . So I wanted you to be the first to know.”

King, quite professional, did not indicate any sense of relief upon hearing the news. Bachmann was behind a podium set on a low stage in the college hockey rink. In black suit and high heels she provided some contrast to the six men who looked like they were about to be inducted into the local Rotary Club; smiling, amiable, eager to please and ready to drop the hammer at any given moment on Barack Obama for everything from unemployment to health care to same-sex marriage. The crowd for the debate was middle-aged, white, patriotic and ready to roll for anyone who could convince them that competence could beat charisma in 2012.

Moments before the TV light went on an old guy with a white beard shouted, “Let’s do the Pledge.” The CNN floor producer said, “What?” and the old guy repeated himself, louder: “Let’s do the Pledge.”

“You want to lead it?” the floor producer asked.

“Yeah, “ the old guy said. And he did. The crowd stood, hand over hearts, reciting the Pledge of Allegiance to great applause.

New Hampshire is not that different from 49 other states. Anxiety and apprehension fill the air. Confidence in the country is shaky as people pay over four dollars a gallon for gas, listen to news about staggering debt, watch home prices and wages wallow in the shadow of what sure seems like a double-dip or, at least, a never-ending recession.

In the morning, traffic on I-93 South toward Boston resembles the highway from Baghdad to Kuwait as thousands of New Hampshire residents head to jobs in Massachusetts. The unemployment rate here is merely 4.7%, nearly half the national average but fear is contagious and politics seems to offer little hope as more and more candidates behave like seismographs, reacting to each poll and looking at a future they measure in two or four year increments. What happens in the next election is a larger concern than what happens to the next generation.

On the stage at St. Anselm’s, Mitt Romney, appearing somewhat weary, didn’t have to worry about being ganged up on; the others took a pass on getting personal, allowing Romney to look like the leader of the pack. Newt Gingrich continued a pathetic act, posing as a deep thinker while Ron Paul, Tim Pawlenty, Rick Santorum and Herman Cain merely occupied space on a night when many in the crowd wondered what the score was in a real game being played an hour’s drive south: the Boston Bruins were beating the Vancouver Canucks 5-2 in Game Six of the Stanley Cup Finals.

Of course other numbers were never mentioned: Our exhausted nation has been at war for 10 years. Twenty-three residents of New Hampshire have been killed in Iraq, 13 more in Afghanistan. Hundreds have been wounded, physically as well as psychically, and require costly care that is rarely mentioned by any candidate.

Earlier in the day, before the debate at St. Anselm’s, a car stopped on a bridge on Route 114 near Henniker, about 20 miles from Manchester. There is a sign dedicating the bridge to the memory of Sgt. Russell M. Durgin, 10th Mountain Division, United States Army. He grew up in Henniker and was killed in the Korengal Valley, Kunar Province, Afghanistan. He died June 13, 2006 at the age of 23 in a war that seems to be an after-thought for so many in politics on the fifth anniversary of the day his loss fractured a family forever.

Mar. 1, 2011

BOSTON — The Harvard community — and people the world over — is mourning the death of Reverend Peter Gomes, the man who ran the university’s Memorial Church for over forty years.

Gomes died Monday night because of complications from a stroke he had in December. He was 68.

|

| The Reverend Peter Gomes died Monday at the age of 68, after a more-than 40-year ministry at Harvard University. |

Gomes’ longtime friend, writer and columnist Mike Barnicle, met Gomes because the two would regularly spend early mornings at the same restaurant. “He was an education to sit with, next to, to listen to, a sheer education. Not just in terms of his moral values but his view on the world,” Barnicle told WGBH’s Emily Rooney on Tuesday.

A black, openly gay minister, Gomes was a decided rarity. He came out about his sexuality in 1991.

He was also politically conservative for most of his career, although he changed his political affiliation to Democrat to vote for Gov. Deval Patrick in 2006.

Barnicle said Gomes learned from his own experience being different, and set out to help others with theirs.

“He was was an expert at honing in on the demonization of people,” Barnicle said. “He could see people and institutions being demonized well before it would become apparent tthat they were being demonized.”

That, Barnicle said, gave Gomes a sense of fairness that underguarded his political and religious beliefs.

“It’s not fair to go after people because of who they are, or because of their sexual orientation, or because of their color, or because of their income, or because of their zip code. That’s who he was, he was an expert in what’s fair,” Barnicle said.

Gomes was known for his soaring, intricate speaking style. “I like playing with words and structure,” he said once, “Marching up to an idea, saluting, backing off, making a feint and then turning around.”

“His sermons were actually high theater in my mind,” Barnicle remembered.

Gomes did not leave behind a memoir; He said he’d start work on it when he retired, at 70. It’s a shame, Barnicle said. “We need more of him than just a memoir, we need people like him every day.”

Gomes reflected on his life’s work — and his death — on Charlie Rose’s talk show in 2007.

I even have the tombstone the verse on my stone is to be from 2 Timothy. “Study to show thyself approved unto God a workman who needeth not to be ashamed, rightly dividing the word of truth.” That’s what I try to do, that’s what I want people to thnk of me after I’m gone. When I was young, we all had to memorize vast quantities of scripture and I remember that passage from Timothy I thought, ‘Hey that’s not a bad life’s work.’ And in a way I’ve tried to live into it. So my epitaph is not going to be new to me, it’s the path I have followed in my ministry and my life.

Mike Barnicle talks about the baseball gloves he’s had since 1954. “The Tenth Inning,” is a two-part, four-hour documentary film directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick that premieres this week, September 28 & 29th at 8pm ET on PBS. A new chapter in Burns’s landmark 1994 series, “Baseball,” “The Tenth Inning” tells the tumultuous story of the national pastime from the 1990s to the present day.

Mark Feeney from the Boston Globe says, “Mike Barnicle, who toiled for many years at this newspaper, serves as representative of Red Sox Nation. One of his great strengths on both page and screen has always been what a potent and vivid presence he has.”

Mike Barnicle talks about the Red Sox loss of 2003 to the Yankees and how it impacted his son, Tim. “The Tenth Inning,” is a two-part, four-hour documentary film directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick that premieres this week, September 28 & 29th at 8pm ET on PBS. A new chapter in Burns’s landmark 1994 series, “Baseball,” “The Tenth Inning” tells the tumultuous story of the national pastime from the 1990s to the present day.

David Barron of the Houston Chronicle calls Barnicle’s contribution to the film “perhaps the most valuable addition… (Barnicle) provokes simultaneous laughter and tears on the burden of passing his love of the Red Sox to a second generation….”

“The tale of the Sox bookend years of failure and triumph are given a personal connective thread by former Globe columnist Mike Barnicle, who frames the story through the eyes of his children and his late mother, who, Barnicle recalls, used to sit on a porch in Fitchburg, Mass., her nylons rolled down, listening to the Sox on the radio and keeping score on a sheet of paper.” — Gordon Edes for ESPN.com

Watch here: https://video.pbs.org/video/1596452376/#

Wednesday, December 9, 2009

The Afghan War Through a Marine Mother’s Eyes

By Mike Barnicle

Nearly everything is a sad a sad reminder for Mélida Arredondo: the news on TV, stories in the paper, speeches of Barack Obama and others who talk about a war that seems to have lasted so long and affected so many lives, those lost as well as those left behind.

“Did your son like the Marine Corps?” I ask her.

“Yes,” she replies. “He loved it.”

“And why did he join?”

“Too poor to go to college,” Mélida Arredondo says.

Alexander Arredondo enlisted at 17 and was killed at 20 in Najaf during his second deployment in Iraq. He died on his father’s birthday, Aug. 25, 2004, when Carlos Arredondo turned 44.

“My husband almost killed himself in grief,” his wife says. “The day [the Marines] came to tell us Alex was dead, he poured gasoline all over himself and all over the inside of [their] car and lit it on fire. He survived … physically.”

Read the rest of Mike’s column at Time.com

*NEW* True Compass: The Life of Senator Edward M. Kennedy

THURSDAY, DECEMBER 3, 2009 6:00-7:30 PM

Victoria Reggie Kennedy introduces historians Doris Kearns Goodwin, Michael Beschloss and Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne, who will discuss Senator Kennedy’s memoir, True Compass, his role in history and his legacy with political analyst, Mike Barnicle.

Seating is limited, first come, first served.

Friday, Oct. 16, 2009

Last week, Laura and Gary Sklaver buried their oldest boy, Ben, who was 32 when killed by a suicide bomber in the remote village of Murcheh in the distant land of Afghanistan. Ben was a captain in the United States Army. Now he has become one of 804 Americans, 37 from Connecticut, to lose their lives in an expanding war that belongs mostly to the parents and families of those who serve a nation preoccupied by a wounded economy and political polarization.

“He didn’t have to go,” Laura Sklaver said the other day. “His obligation was up in May.”

“But he was recalled in March,” Gary Sklaver added. “And he didn’t want to leave his men.”

Ben Sklaver grew up drawn to service. He admired his grandfather who served with Patton’s Army in World War II. He joined ROTC at Tufts, received a Master’s in international relations from the Fletcher School of Diplomacy, was commissioned as an officer in the Army Reserve in 2003 and became convinced that a world consumed with conflict and terror might be changed by Americans bringing clean water, medicine and food as much as by drones, missiles and military might.

09/21/09: Barnicle has a word to say about how technology is affecting the art of letter writing and penmanship being taught in schools today.

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/09/21/92109-writingpenmanship.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

09/18/09: Barnicle talks about Jared Monti receiving the Medal of Honor yesterday.

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/09/18/91809-jared-montimedal-of-honor.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

9/11/09: Barnicle remembers September 11, 2001, specifically focusing on how we all felt the next day when we were one people united against a common foe.

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/09/11/91109-remembering-911.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

8/31/09: Barnicle talks about the life of Michael Davey, a 34-year-old police officer, war veteran, husband and father cut short after he was struck by a 79-year-old driver last week.

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/08/31/83109-michael-davey.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

Here was Ted Kennedy, 74-year-old son, brother, father, husband, Senator, living history, American legend. He was sitting on a wicker chair on the front porch of the seaside home that held so much of his life within its walls. He was wearing a dark blue blazer and a pale blue shirt. He was tieless and tanned on a spectacular October morning in 2006, and he was smiling too because he could see his boat, the Mya, anchored in Hyannis Port harbor, rocking gently in a warm breeze that held a hint of another summer just passed. Election Day, the last time his fabled name would appear on a ballot, was two weeks away.

“When you’re out on the ocean,” he was asked that day, “do you ever see your brothers?”

“Sure,” Kennedy answered, his voice a few decibels above a whisper. “All the time … all the time. There’s not a day I don’t think of them. This is where we all grew up. There have been some joyous times here. Difficult times too.

“We all learned to swim here. Learned to sail. I still remember my brother Joe, swimming with him here, before he went off to war. My brother Jack, out on the water with him … I remember it all so well. He lived on the water, fought on the water.”

He paused then, staring toward Nantucket Sound. Here he was not the last living brother from a family that had dominated so much of the American political landscape during the second half of the 20th century; he was simply a man who had lived to see dreams die young and yet soldiered on while carrying a cargo of sadness and responsibility. (See pictures from Ted Kennedy’s life and career.)

“The sea … there are eternal aspects to the sea and the ocean,” he said that day. “It anchors you.”

He was home. Who he was — who he really was — is rooted in the rambling, white clapboard house in Hyannis Port to which he could, and would, retreat to recover from all wounds.

“How old were you when your brother Joe died?” Ted was asked that morning.

“Twelve,” he replied. “I was 12 years old.”

Joe Kennedy Jr., the oldest of nine children, was the first to die — at 29 — when the plane he was flying on a World War II mission exploded over England on Aug. 12, 1944.

“Mother was in the kitchen. Dad was upstairs. I was right here, right on this porch, when a priest arrived with an Army officer. I remember it quite clearly,” Kennedy said.

Kennedy remembered it all. The wins, the losses and the fact there were never any tie games in his long life. Nobody was neutral when it came to the man and what he accomplished in the public arena. And few were aware of the private duties he gladly assumed as surrogate father to nieces and nephews who grew up in a fog of myth.

He embraced strangers. Brian Hart met Kennedy at Arlington National Cemetery on a cold, gray November day in 2003. Brian and his wife Alma were burying their 20-year-old son, Army Private First Class John Hart, who had been killed in Iraq. “I turned around at the end of the service, and that was the first time I met Senator Kennedy,” the father of the dead soldier said. “He was right there behind us. I asked him if he could meet with me later to talk about how and why our son died — because he did not have the proper equipment to fight a war. He was in a vehicle that was not armored.

“That month Senator Kennedy pushed the Pentagon to provide more armored humvees for our troops. Later, when I thanked him, he told me it wasn’t necessary, that he wanted to thank me for helping focus attention on the issue and that he knew what my wife and I were feeling because his mother — she was a Gold Star mother too.

“On the first anniversary of John’s death, he and his wife Vicki joined Alma and me at Arlington,” Brian said. “He told Alma that early morning was the best time to come to Arlington. It was quiet and peaceful, and the crowds wouldn’t be there yet. He had flowers for my son’s grave. With all that he has to do, he remembered our boy.”

Ted Kennedy was all about remembering. He remembered birthdays, christenings and anniversaries. He was present at graduations and funerals. He organized picnics, sailing excursions, sing-alongs at the piano and touch-football games on the lawn. He presided over all things family. He was the navigator for those young Kennedys who sometimes seemed unsure of their direction as life pulled them between relying on reputation and reality.

An emotional man, he became deeply devoted to his Catholic faith and his second wife Vicki. He even learned to view the brain cancer that eventually killed him as an odd gift — a gradual fading of a kind that would be easier for his family and friends to come to terms with than the violent and sudden loss of three brothers and a sister, Kathleen. He, at least, was given the gift of time to prepare.

The day after Thanksgiving in 2008, six months after his diagnosis, Kennedy had a party. He and Vicki invited about 100 people to Hyannis Port. Chemotherapy had taken a toll on Ted’s strength, but Barack Obama’s electoral victory had invigorated him. His children, stepchildren and many of his nieces and nephews were there. So were several of his oldest friends, men who had attended grammar school, college or law school with Kennedy. Family and friends: the ultimate safety net. (See video of Kennedy from the 2008 Democratic National Convention.)

Suddenly, Ted Kennedy wanted to sing. And he demanded everyone join him in the parlor, where he sat in a straight-backed chair beside the piano. Most of the tunes were popular when all the ghosts were still alive, still there in the house. Ted sang “Some Enchanted Evening,” and everyone chimed in, the smiles tinged with a touch of sadness.

The sound spilled out past the porch, into a night made lighter by a full moon whose bright glare bounced off the dark waters of Nantucket Sound, beyond the old house where Teddy — and he was always “Teddy” here — mouthed the lyrics to every song, sitting, smiling, happy to be surrounded by family and friends in a place where he could hear and remember it all. And as he sang, his blue eyes sparkled with life, and for the moment it seemed as if one of his deeply felt beliefs — “that we will all meet again, don’t know where, don’t know when” — was nothing other than true.

“I love living here,” Ted Kennedy once said. “And I believe in the Resurrection.”

Barnicle was a columnist at the Boston Globe for 25 years

![]()

Wednesday, August 26th 2009, 6:30 PM

He died on a soft summer night, at home in Hyannis Port, a few days after a storm, the edge of another hurricane, ripped the waters of Nantucket Sound, turning the sky an angry gray.

But now, on the day after he died, the air was clear and there was only the heat of the August sun beating down on the boat, the Mya, that Ted Kennedy so often took to sea, seeking comfort from the past and refuge from the illness now ravaging his system.

Some months before he died, he sat on the porch of the big, white clapboard house he shared with his wife, Vicki, his dogs and his memories – the Hyannis Port house both a home and a museum containing the story of seven decades in the life of one man and a single country.

“When you’re out on the ocean,” I asked, “do you ever see your brothers?”

“Sure, all the time, all the time,” he answered, his voice a whisper. “There’s not a day I don’t think of them. This is where we all grew up.”

And this is where it came to an end, the long dynastic thread woven through world wars, politics, scandal and redemption.

At 77, Edward Moore Kennedy was a man who learned to live with his flaws, his failures and a prematurely ordained future that never was and, after 1969, could never be.

He was the most Irish of four brothers, had the loudest laugh and the biggest voice. He was familiar with pain, emotional and physical. He was sentimental, given to song, poetry and painting. His own hand-painted watercolors adorn the walls of his house.

He suffered greatly from self-inflicted wounds – Chappaquiddick, an affinity for alcohol – as well as the weight of constant expectation that he would, could, might rise and eventually take the White House.

But disruptions caused by the hand of two different gunmen in two different American cities altered him forever, detoured him from the family dream, pushed him to live without a calendar, measuring his days and hours by the whim of a fate he knew he could never truly control.

He became, Kennedy did, a religious man, often attending early Mass with his wife at Our Lady of Victory in Centerville on Cape Cod, knowing that his Catholic faith was rooted in forgiveness.

It is easy to consider how Ted Kennedy might have approached the Lord:

“Bless me Father for I have sinned. It has been – What? – Three weeks? Three years? Three decades? – since my last confession.”

And his penance, if you will, was to serve as a surrogate for three dead brothers and the cargo of lost and wounded children left in the wake of war and assassination; to lose and immerse himself in the freedom of being a legislator rather than be shackled by a myth or become a political vessel for others driven by dreams of dynasty.

He carried his Cross through all the decades, carried it with honor and nobility. He heard every slur, each slander, lost his only quest for the Oval Office and emerged from defeat with a deeper knowledge of who he was and what was meant to be: a life lived in the United States Senate, to negotiate, deal and fight for laws that simply changed how we lived.

Now, the house by the sea, a place once filled with high hopes and even higher ambition, is quiet. And last night’s dusk arrived with a brutal truth: This man who came through the fire of life, scarred but whole, is silent forever, while the fog of memory, seven decades deep, becomes legend on the summer wind.

8/14/09: Barnicle remembers Eunice Kennedy Shriver

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/08/14/81409-eunice-kennedy-shriver.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

Yarmouth Police Lt. Steven Xiarhos pauses at the casket of his son Nicholas Xiarhos. (Photo by Steve Heaslip / Cape Cod Times)

On a soft summer morning last week, when much of the nation’s media exploded with coverage of the prior night’s White House gathering of a president, a professor, and a policeman, hundreds of ordinary strangers stood like silent sentries along a busy Cape Cod road to salute a funeral hearse carrying a noble young Marine killed in Afghanistan. His name was Nicholas Xiarhos, Corporal Nicholas Xiarhos, 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines, 21 when a war fought by so few claimed him as one of the latest of 768 victims wearing the uniform of the United States of America in Operation Enduring Freedom, the violent effort to tame the Taliban in a land largely unchanged across the centuries.

A Cadillac hearse slowly carried the flag-draped coffin along Route 28, from St. George’s Greek Orthodox Church in Centerville to Bourne and the National Cemetery where Xiarhos was buried. The procession stretched for miles beneath a warm drizzle and a gunmetal gray sky.

Along the way, there were people, hundreds of them; people who were, for the moment, not consumed with health-care debates, deficits, bailouts for big banks, birthers, or house arrests in Cambridge.

It passed ice cream shops and supermarkets, malls and movie theaters, pharmacies and golf clubs, and all along the way, there were people, hundreds of them; people who were, for the moment, not consumed with health-care debates, deficits, bailouts for big banks, birthers, or house arrests in Cambridge.

They stood by their cars, stopped by the side of the road to let the long parade of grief pass. They held children on their shoulders, American flags and homemade posters in their grasp. They had hands over hearts and tears in their eyes for a boy most never met and a crushed family: the father, Lieutenant Steven Xiarhos, wearing the full dress uniform of the Cape Cod police department he has served for 30 years, the mother, Lisa Xiarhos, the dead Marine’s twin sisters, and younger brother.

The roadside mourners were of all ages and from several states, joined now in a unique American moment, a tribute to a casualty of a long war that has affected so few families in this country of such short memory. Witnesses to brutal reality.

Steven Xiarhos snapped this photo of his wife, Lisa, and their son, Nick, at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina on Sept. 1.At the cemetery, the mist became rain and thunder announced itself in the distance. A color guard responded to nature’s noise with a 21-gun salute. A bagpipe brigade played “God Bless America.” His mother was presented with the gift of a grateful nation, the folded flag that protected the coffin carrying a son who died protecting others.

Steven Xiarhos snapped this photo of his wife, Lisa, and their son, Nick, at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina on Sept. 1.At the cemetery, the mist became rain and thunder announced itself in the distance. A color guard responded to nature’s noise with a 21-gun salute. A bagpipe brigade played “God Bless America.” His mother was presented with the gift of a grateful nation, the folded flag that protected the coffin carrying a son who died protecting others.

Three summers ago, Nick Xiarhos graduated from high school. In the 36 months since his senior prom, he fought in Iraq, returned to Cape Cod, redeployed to Afghanistan, and had now come home forever to a country and a culture that simply does not place enough value on the loss of those who go to a war that sometimes seems as forgotten as those who fight it.

Mike Barnicle has been a newspaper—remember them?—columnist for 35 years. He is a contributing commentator on MSNBC’s Morning Joe program.

Mike Barnicle is a veteran print and broadcast journalist recognized for his street-smart, straightforward style honed over nearly four decades in the field. The Massachusetts native has written 4,000-plus columns collectively for The Boston Globe, Boston Herald and the New York Daily News, and continues to champion the struggles and triumphs of the every man by giving voice to the essential stories of today on television, radio, and in print.