Deadline Artists: America’s Greatest Newspaper Columns

Edited by John Avlon, Jesse Angelo & Errol Louis

At a time of great transition in the news media, Deadline Artists celebrates the relevance of the newspaper column through the simple power of excellent writing. It is an inspiration for a new generation of writers—whether their medium is print or digital-looking to learn from the best of their predecessors.

This new book features two of Mike’s columns from The Boston Globe. The book says, “Barnicle is to Boston what Royko was to Chicago and Breslin is to New York—an authentic voice who comes to symbolize a great city. Almost a generation younger than Breslin & Co., Barnicle also serves as the keeper of the flame of the reported column. A speechwriter after college, Barnicle’s column with The Boston Globe ran from 1973 to 1998. He has subsequently written for the New York Daily News and the Boston Herald, logging an estimated four thousand columns in the process. He is also a frequent guest on MSNBC’s Morning Joe as well as a featured interview in Ken Burns’s Baseball: The Tenth Inning documentary.”

Read the columns here (you can buy the book by clicking here)

“Steak Tips to Die For” – Boston Globe – November 7, 1995

Those who think red meat might be bad for you have a pretty good argument this morning in the form of five dead guys killed yesterday at the 99 Restaurant in Charlestown. It appears that that two late Luisis, Bobby, the father, and Roman, his son, along with their three pals, sure did love it because there was so much beef spread out in front of the five victims that their table-top resembled a cattle drive.

“All that was missing was the marinara,” a detective was saying yesterday. “If they had linguini and marinara it would have been like that scene in The Godfather where Michael Corleone shoots the Mafia guy and the cop. But it was steak tips.”

Prior to stopping for a quick bite, Roman Luisi was on kind of a roll. According to police, he recently beat a double-murder charge in California. Where else?

But that was then and this is now. And Sunday night, he got in a fight in the North End. Supposedly, one of those he fought with was Damian Clemente, 20 years old and built like a steamer trunk. Clemente, quite capable of holding a grudge, is reliably reported to have sat on Luisi.

Plus, it is now alleged that at lunch yesterday, young Clemente, along with Vincent Perez, 27, walked into the crowded restaurant and began firing at five guys in between salads and entrée. The 99 is a popular establishment located at the edge of Charlestown, a section of the city often pointed to as a place where nearly everyone acts like Marcel Marceau after murders take place in plain view of hundreds.

Therefore, most locals were quick to point out that all allegedly involved in the shooting—the five slumped on the floor as well as the two morons quickly captured outside—were from across the bridge. Both the alleged shooters and the five victims hung out in the North End.

However, yesterday, it appears, everyone was playing an away game. For those who still think “The Mob” is an example of a talented organization capable of skillfully executing its game plan, there can be only deep disappointment in the aftermath of such horrendous, noisy and public violence.

It took, oh, about 45 seconds for authorities to track down Clemente and Perez. Clemente is of such proportions that his foot speed is minimal. And it is thought that his partner Perez’s thinking capacity is even slower than Clemente’s feet.

Two Everett policeman out of uniform—Bob Hall and Paul Durant—were having lunch a few feet away from where both Luisis and the others were having the last supper. The two cops have less than five years’ experience combined but both came up huge.

“They didn’t try anything crazy inside. They didn’t panic,” another detective pointed out last night. “They followed the two shooters out the door, put them down and held them there. They were unbelievably level-headed, even when two Boston cops arrived and had their guns drawn on the Everett cops because they didn’t know who they were, both guys stayed cool and identified themselves. And they are going to make two truly outstanding witnesses.”

The two Boston policemen who arrived in the parking lot where Clemente and Perez were prone on the asphalt were Tom Hennessey and Stephen Green. They were working a paid detail nearby which, all things being equal, immediately led one official to cast the event in its proper, parochial perspective: “This ought to put an end to the argument to do away with paid details,” he said. “Hey, ask yourself this question: You think a flagman could have arrested these guys?”

The entire event—perhaps four minutes in duration, involving at least 13 shots, five victims and two suspects caught—is a bitter example of how downsizing has affected even organized crime. For several years, the federal government has enforced mandatory retirement rules—called jail—on several top local mob executives.

What’s left are clowns who arrive for a great matinee murder in a beat-up blue Cadillac and a white Chrysler that look like they are used for Bumper-Car. The shooters then proceed to leave a restaurant filled with the smell of cordite and about 37 people capable of picking them out of a lineup.

“Part of it was kind of like in the movies, but part of it wasn’t,” an eyewitness said last night. “The shooting part was like you see in a movie but the fat guy almost slipped and fell when he was getting away. That part you don’t see in a movie. But what a mess that table was.”

“We have a lot of evidence, witnesses and even a couple weapons,” a detective pointed out last evening. “But the way things are going in this country it would not surprise me if the defense argues that they guys were killed by cholesterol.”

“New Land, Sad Story” – Boston Globe – November 23, 1995

Three Cadillac hearses were parked on Hastings Street outside Calvary Baptist Church in Lowell Tuesday morning as an old town wrestled with new grief. Inside, the caskets had been placed together by the altar while the mother of the dead boys, a Cambodian woman named Chhong Yim, wept so much it seemed she cried for a whole city.

The funeral occurred two days before the best of American holidays and revolved around a people, many of whom have felt on occasion that God is symbolized by stars, stripes and the freedom to walk without fear. But a bitter truth was being buried here as well because now every Cambodian man, woman and child knows that despite fleeing the Khmer Rouge and soldiers who killed on whim, nobody can run forever from a plague that is as much a bitter part of this young country as white meat and cranberry sauce.

The dead children were Visal Men, 15, along with his two brothers Virak, 14, and Sovanna, 9, born in the U.S.A. They were shot and stabbed last week when the mother’s friend, Vuthy Seng, allegedly became enraged at being spurned by Chhong Yim, who chose her children over Seng.

There sure are enough sad stories to go around on any given day. However, there aren’t many to equal the slow demise of a proud, gentle culture—Cambodian—as it is bastardized by the clutter and chaos we not only allow to occur but willingly accept as a cost of democracy.

The three boys died slowly; first one, then the other in a hospital and, finally, the third a few days after Seng supposedly had charged into the apartment with a gun and a machete. He shot and hacked all three children along with their sister, Sathy Men, who is 13 and stood bewildered beside her howling mother, the two of them survivors of a horror so deep their lives are forever maligned.

At 10:45, as the funeral was set to begin, two cops on motorcycles came up Hastings ahead of a bus filled with children from Butler Middle School. The boys and girls walked in silence into the chapel to pray for the dead who have left a firm imprint on their adopted hometown.

The crowd of mourners was thrilling in its diversity. There were policemen, firefighters, teachers and shopkeepers. The young knelt shoulder-to-shoulder with the old. There were Catholic nuns and Buddhist priests. There were friends of the family as well as total strangers summoned only by tragedy.

A little after 11 a.m., Hak Sen, who drove from Rhode Island, parked his car by the post office and headed toward Calvary Baptist Church.

“I am late. I got lost,” Hak Sen said.

“Are you a friend of the family?” he was asked.

“No,” he replied. “I do not know them. I come out of respect and sadness. We all make a terrible journey to come here to America and this is very, very bad.”

Hak Sen said he and his family were from Battambang Province, along the Thai-Cambodian border. He said that he served in the army before Pol Pot took over his country and that he and his family were forced to flee but not all made it to the refugee camps.

“I am lucky man,” Hak Sen pointed out. “I survive. My wife, she survive and two of our children, they survive.”

“Did you lose any children?” he was asked.

“Yes,” he said. “I lost three boys, just like this woman. Three boys and our daughter. They all dead. The malaria killed them in the jungle. There was not enough food and no water and they were young and could not fight the disease and they died. They all dead. My mother and father too.”

The innocent children inside the church as well as the big-hearted citizens of Lowell along with the majority of people who will buy a paper or carve a turkey today simply have no idea of the epic, tragic struggle of the Cambodians. They left a country where they were killed for owning a ballpoint pen or wearing a pair of eyeglasses to arrive in this country where, each day, we become more and more narcoticized by the scale of violence around us.

At the conclusion of the service, Lowell detectives Mike Durkin, John Boutselis and Phil Conroy helped carry the caskets to the hearses. The procession wound slowly through city streets, pausing for a few seconds outside the Butler School, where pupils lined both sides of the road like grieving sentries as the entourage entered Westlawn Cemetery.

“This is as sad as it gets,” said Roger LaPointe, a cemetery worker. “We cut the first two graves the end of last week but the funeral director told us we better hold on. When the third boy died, we had to cut it some more. It’s an awful thing. That hole just kept getting bigger.”

Glaring Omission in Republican Debate: Why So Little Mention of Our Costly War?

By Mike Barnicle

Manchester, N.H. – At ten past eight Monday evening, Michele Bachmann decided to separate herself from the six guys next to her on the stage by telling John King of CNN why she had come to St. Anselm’s College. She did this on the fifth anniversary of a day when a young man from New Hampshire was killed in a war hardly mentioned last night.

“John…I just want to make an announcement,” she said as the first big TV debate among Republican candidates for president began, “I filed today my paperwork to seek the office of the presidency of the United States. . . . So I wanted you to be the first to know.”

King, quite professional, did not indicate any sense of relief upon hearing the news. Bachmann was behind a podium set on a low stage in the college hockey rink. In black suit and high heels she provided some contrast to the six men who looked like they were about to be inducted into the local Rotary Club; smiling, amiable, eager to please and ready to drop the hammer at any given moment on Barack Obama for everything from unemployment to health care to same-sex marriage. The crowd for the debate was middle-aged, white, patriotic and ready to roll for anyone who could convince them that competence could beat charisma in 2012.

Moments before the TV light went on an old guy with a white beard shouted, “Let’s do the Pledge.” The CNN floor producer said, “What?” and the old guy repeated himself, louder: “Let’s do the Pledge.”

“You want to lead it?” the floor producer asked.

“Yeah, “ the old guy said. And he did. The crowd stood, hand over hearts, reciting the Pledge of Allegiance to great applause.

New Hampshire is not that different from 49 other states. Anxiety and apprehension fill the air. Confidence in the country is shaky as people pay over four dollars a gallon for gas, listen to news about staggering debt, watch home prices and wages wallow in the shadow of what sure seems like a double-dip or, at least, a never-ending recession.

In the morning, traffic on I-93 South toward Boston resembles the highway from Baghdad to Kuwait as thousands of New Hampshire residents head to jobs in Massachusetts. The unemployment rate here is merely 4.7%, nearly half the national average but fear is contagious and politics seems to offer little hope as more and more candidates behave like seismographs, reacting to each poll and looking at a future they measure in two or four year increments. What happens in the next election is a larger concern than what happens to the next generation.

On the stage at St. Anselm’s, Mitt Romney, appearing somewhat weary, didn’t have to worry about being ganged up on; the others took a pass on getting personal, allowing Romney to look like the leader of the pack. Newt Gingrich continued a pathetic act, posing as a deep thinker while Ron Paul, Tim Pawlenty, Rick Santorum and Herman Cain merely occupied space on a night when many in the crowd wondered what the score was in a real game being played an hour’s drive south: the Boston Bruins were beating the Vancouver Canucks 5-2 in Game Six of the Stanley Cup Finals.

Of course other numbers were never mentioned: Our exhausted nation has been at war for 10 years. Twenty-three residents of New Hampshire have been killed in Iraq, 13 more in Afghanistan. Hundreds have been wounded, physically as well as psychically, and require costly care that is rarely mentioned by any candidate.

Earlier in the day, before the debate at St. Anselm’s, a car stopped on a bridge on Route 114 near Henniker, about 20 miles from Manchester. There is a sign dedicating the bridge to the memory of Sgt. Russell M. Durgin, 10th Mountain Division, United States Army. He grew up in Henniker and was killed in the Korengal Valley, Kunar Province, Afghanistan. He died June 13, 2006 at the age of 23 in a war that seems to be an after-thought for so many in politics on the fifth anniversary of the day his loss fractured a family forever.

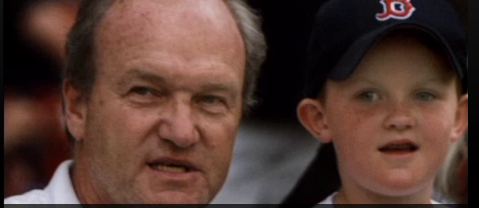

Mike Barnicle talks about the baseball gloves he’s had since 1954. “The Tenth Inning,” is a two-part, four-hour documentary film directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick that premieres this week, September 28 & 29th at 8pm ET on PBS. A new chapter in Burns’s landmark 1994 series, “Baseball,” “The Tenth Inning” tells the tumultuous story of the national pastime from the 1990s to the present day.

Mark Feeney from the Boston Globe says, “Mike Barnicle, who toiled for many years at this newspaper, serves as representative of Red Sox Nation. One of his great strengths on both page and screen has always been what a potent and vivid presence he has.”

Mike Barnicle talks about the Red Sox loss of 2003 to the Yankees and how it impacted his son, Tim. “The Tenth Inning,” is a two-part, four-hour documentary film directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick that premieres this week, September 28 & 29th at 8pm ET on PBS. A new chapter in Burns’s landmark 1994 series, “Baseball,” “The Tenth Inning” tells the tumultuous story of the national pastime from the 1990s to the present day.

David Barron of the Houston Chronicle calls Barnicle’s contribution to the film “perhaps the most valuable addition… (Barnicle) provokes simultaneous laughter and tears on the burden of passing his love of the Red Sox to a second generation….”

“The tale of the Sox bookend years of failure and triumph are given a personal connective thread by former Globe columnist Mike Barnicle, who frames the story through the eyes of his children and his late mother, who, Barnicle recalls, used to sit on a porch in Fitchburg, Mass., her nylons rolled down, listening to the Sox on the radio and keeping score on a sheet of paper.” — Gordon Edes for ESPN.com

Watch here: https://video.pbs.org/video/1596452376/#

09/21/09: Barnicle has a word to say about how technology is affecting the art of letter writing and penmanship being taught in schools today.

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/09/21/92109-writingpenmanship.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

Barnicle on Kennedy: Of Memory and the Sea

Here was Ted Kennedy, 74-year-old son, brother, father, husband, Senator, living history, American legend. He was sitting on a wicker chair on the front porch of the seaside home that held so much of his life within its walls. He was wearing a dark blue blazer and a pale blue shirt. He was tieless and tanned on a spectacular October morning in 2006, and he was smiling too because he could see his boat, the Mya, anchored in Hyannis Port harbor, rocking gently in a warm breeze that held a hint of another summer just passed. Election Day, the last time his fabled name would appear on a ballot, was two weeks away.

“When you’re out on the ocean,” he was asked that day, “do you ever see your brothers?”

“Sure,” Kennedy answered, his voice a few decibels above a whisper. “All the time … all the time. There’s not a day I don’t think of them. This is where we all grew up. There have been some joyous times here. Difficult times too.

“We all learned to swim here. Learned to sail. I still remember my brother Joe, swimming with him here, before he went off to war. My brother Jack, out on the water with him … I remember it all so well. He lived on the water, fought on the water.”

He paused then, staring toward Nantucket Sound. Here he was not the last living brother from a family that had dominated so much of the American political landscape during the second half of the 20th century; he was simply a man who had lived to see dreams die young and yet soldiered on while carrying a cargo of sadness and responsibility. (See pictures from Ted Kennedy’s life and career.)

“The sea … there are eternal aspects to the sea and the ocean,” he said that day. “It anchors you.”

He was home. Who he was — who he really was — is rooted in the rambling, white clapboard house in Hyannis Port to which he could, and would, retreat to recover from all wounds.

“How old were you when your brother Joe died?” Ted was asked that morning.

“Twelve,” he replied. “I was 12 years old.”

Joe Kennedy Jr., the oldest of nine children, was the first to die — at 29 — when the plane he was flying on a World War II mission exploded over England on Aug. 12, 1944.

“Mother was in the kitchen. Dad was upstairs. I was right here, right on this porch, when a priest arrived with an Army officer. I remember it quite clearly,” Kennedy said.

Kennedy remembered it all. The wins, the losses and the fact there were never any tie games in his long life. Nobody was neutral when it came to the man and what he accomplished in the public arena. And few were aware of the private duties he gladly assumed as surrogate father to nieces and nephews who grew up in a fog of myth.

He embraced strangers. Brian Hart met Kennedy at Arlington National Cemetery on a cold, gray November day in 2003. Brian and his wife Alma were burying their 20-year-old son, Army Private First Class John Hart, who had been killed in Iraq. “I turned around at the end of the service, and that was the first time I met Senator Kennedy,” the father of the dead soldier said. “He was right there behind us. I asked him if he could meet with me later to talk about how and why our son died — because he did not have the proper equipment to fight a war. He was in a vehicle that was not armored.

“That month Senator Kennedy pushed the Pentagon to provide more armored humvees for our troops. Later, when I thanked him, he told me it wasn’t necessary, that he wanted to thank me for helping focus attention on the issue and that he knew what my wife and I were feeling because his mother — she was a Gold Star mother too.

“On the first anniversary of John’s death, he and his wife Vicki joined Alma and me at Arlington,” Brian said. “He told Alma that early morning was the best time to come to Arlington. It was quiet and peaceful, and the crowds wouldn’t be there yet. He had flowers for my son’s grave. With all that he has to do, he remembered our boy.”

Ted Kennedy was all about remembering. He remembered birthdays, christenings and anniversaries. He was present at graduations and funerals. He organized picnics, sailing excursions, sing-alongs at the piano and touch-football games on the lawn. He presided over all things family. He was the navigator for those young Kennedys who sometimes seemed unsure of their direction as life pulled them between relying on reputation and reality.

An emotional man, he became deeply devoted to his Catholic faith and his second wife Vicki. He even learned to view the brain cancer that eventually killed him as an odd gift — a gradual fading of a kind that would be easier for his family and friends to come to terms with than the violent and sudden loss of three brothers and a sister, Kathleen. He, at least, was given the gift of time to prepare.

The day after Thanksgiving in 2008, six months after his diagnosis, Kennedy had a party. He and Vicki invited about 100 people to Hyannis Port. Chemotherapy had taken a toll on Ted’s strength, but Barack Obama’s electoral victory had invigorated him. His children, stepchildren and many of his nieces and nephews were there. So were several of his oldest friends, men who had attended grammar school, college or law school with Kennedy. Family and friends: the ultimate safety net. (See video of Kennedy from the 2008 Democratic National Convention.)

Suddenly, Ted Kennedy wanted to sing. And he demanded everyone join him in the parlor, where he sat in a straight-backed chair beside the piano. Most of the tunes were popular when all the ghosts were still alive, still there in the house. Ted sang “Some Enchanted Evening,” and everyone chimed in, the smiles tinged with a touch of sadness.

The sound spilled out past the porch, into a night made lighter by a full moon whose bright glare bounced off the dark waters of Nantucket Sound, beyond the old house where Teddy — and he was always “Teddy” here — mouthed the lyrics to every song, sitting, smiling, happy to be surrounded by family and friends in a place where he could hear and remember it all. And as he sang, his blue eyes sparkled with life, and for the moment it seemed as if one of his deeply felt beliefs — “that we will all meet again, don’t know where, don’t know when” — was nothing other than true.

“I love living here,” Ted Kennedy once said. “And I believe in the Resurrection.”

Barnicle was a columnist at the Boston Globe for 25 years

![]()

Ted Kennedy failed to match brothers’ legacies, but forged own flawed future

Wednesday, August 26th 2009, 6:30 PM

He died on a soft summer night, at home in Hyannis Port, a few days after a storm, the edge of another hurricane, ripped the waters of Nantucket Sound, turning the sky an angry gray.

But now, on the day after he died, the air was clear and there was only the heat of the August sun beating down on the boat, the Mya, that Ted Kennedy so often took to sea, seeking comfort from the past and refuge from the illness now ravaging his system.

Some months before he died, he sat on the porch of the big, white clapboard house he shared with his wife, Vicki, his dogs and his memories – the Hyannis Port house both a home and a museum containing the story of seven decades in the life of one man and a single country.

“When you’re out on the ocean,” I asked, “do you ever see your brothers?”

“Sure, all the time, all the time,” he answered, his voice a whisper. “There’s not a day I don’t think of them. This is where we all grew up.”

And this is where it came to an end, the long dynastic thread woven through world wars, politics, scandal and redemption.

At 77, Edward Moore Kennedy was a man who learned to live with his flaws, his failures and a prematurely ordained future that never was and, after 1969, could never be.

He was the most Irish of four brothers, had the loudest laugh and the biggest voice. He was familiar with pain, emotional and physical. He was sentimental, given to song, poetry and painting. His own hand-painted watercolors adorn the walls of his house.

He suffered greatly from self-inflicted wounds – Chappaquiddick, an affinity for alcohol – as well as the weight of constant expectation that he would, could, might rise and eventually take the White House.

But disruptions caused by the hand of two different gunmen in two different American cities altered him forever, detoured him from the family dream, pushed him to live without a calendar, measuring his days and hours by the whim of a fate he knew he could never truly control.

He became, Kennedy did, a religious man, often attending early Mass with his wife at Our Lady of Victory in Centerville on Cape Cod, knowing that his Catholic faith was rooted in forgiveness.

It is easy to consider how Ted Kennedy might have approached the Lord:

“Bless me Father for I have sinned. It has been – What? – Three weeks? Three years? Three decades? – since my last confession.”

And his penance, if you will, was to serve as a surrogate for three dead brothers and the cargo of lost and wounded children left in the wake of war and assassination; to lose and immerse himself in the freedom of being a legislator rather than be shackled by a myth or become a political vessel for others driven by dreams of dynasty.

He carried his Cross through all the decades, carried it with honor and nobility. He heard every slur, each slander, lost his only quest for the Oval Office and emerged from defeat with a deeper knowledge of who he was and what was meant to be: a life lived in the United States Senate, to negotiate, deal and fight for laws that simply changed how we lived.

Now, the house by the sea, a place once filled with high hopes and even higher ambition, is quiet. And last night’s dusk arrived with a brutal truth: This man who came through the fire of life, scarred but whole, is silent forever, while the fog of memory, seven decades deep, becomes legend on the summer wind.

8/12/09: Barnicle talks about Miley Cyrus’s pole dancing at the Teen Choice Awards.

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/08/12/81209-miley-cyrus.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

7/27/09: Barnicle tells the story of Marine Cpl. Nicholas Xiarhos, a local 21-year-old man who died recently in Afghanistan, and the minimal newspaper coverage of his and other soldiers’ deaths.

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/07/27/72709-marine-cpl-nicholas-xiarhos.aspx?ref=rss

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

6/29/09: Barnicle remembers Michael Jackson and his place in history.

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/06/29/62909-michael-jackson.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

6/24/09: High school sports teams go unfunded and the terrible impact that has on kids.

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/06/24/62409-high-school-sports.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

6/22/09: On the day Philip Markoff is formally charged with murder, Barnicle talks about the young man’s internet life.

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/06/22/62209-philip-markoff.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

5/15/09: Barnicle talks about the fragility of life after a local college student is killed in a car accident.

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/05/15/51509-life-being-taken-for-granted.aspx?ref=rss

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

8/11/08: Story about the tragic death of a 7-year-old girl over the weekend

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2008/08/11/81108-death-of-a-7-year-old-girl-over-the-weekend.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

A regal funeral closer to home

Mike Barnicle, Globe Staff

7 September 1997

The Boston Globe

Long before yesterday’s funeral began, a huge crowd assembled inside the magnificent church where everyone gathered in a crush of sadness over the death of a sparkling young mother who touched many lives before she was killed in a horrific car crash a week ago, across the ocean, far from home. Mourners came in such numbers that they spilled out the doors of St. Theresa’s Church, onto the sidewalk, and across Centre Street in West Roxbury as police on motorcycles and horseback led two flower-cars and three hearses to the front of a beautiful church filled now with tears and memory.

Yesterday, the wonderful world of Mary Beatty Devane was on display to bury her along with two of her daughters — Elaine, 9, and Christine, 8 — who also lost their lives on a wet road east of Galway City as they headed to Shannon Airport at the conclusion of their vacation. Her husband, Martin, their daughter Brenda, 5, and their son Michael, 2, survived the accident and, after the hearses halted at the curb, Martin Devane emerged from a car, his entire being bent, injured, and slowed by the enormous burden of his tragic loss.

The Devanes represent one of the many anonymous daily miracles of this city’s life. They lived around the corner from where Mary grew up in a house headed by her father, Joe Beatty, the president of Local 223, Laborers Union, who arrived in Boston decades back from the same Irish village, Rusheenamanagh, where Mary’s husband, Martin, was born.

He is a construction worker. She was a nurse. They were married 11 years and their life together cast a contagious glow across their church and their community.

Now, on a splendid summer Saturday, when the world paused for a princess, up the street they came to cry for Mary Theresa Beatty and her children. There were nuns and priests, cops and carpenters, plumbers, teachers, firefighters, and nurses side-by-side with farmers who flew in from rocky fields an ocean away. A global village of friends inside a single city church.

Bagpipes played while 16 pallbearers gently removed three caskets from the steel womb of the hearses. The weeping crowd formed a long corridor of hushed grief as the caskets were carried up the steps and down the aisle toward 17 priests who waited to apply the balm of prayer to the wounded mourners.

Mary Devane worked weekend nights in the emergency room at Faulkner Hospital. When she was not there, she was either caring for her own family or tending to the dying as a hospice nurse.

During her 31 years on earth, she was many things: wife, mother, daughter, sister, nurse, neighbor, healer, helper, compassionate companion to the suffering, angel of mercy for the ill, smiling friend to an entire community that stood yesterday in collective silence in a church cluttered with broken hearts.

As the pallbearers transported their precious cargo, 22 boys and girls from St. Theresa’s Children’s Choir rose alongside the parish choir to sing “Lord of All Hopefulness.” No cameras or celebrities were present — simply the pastor, the Rev. William Helmick, along with all the others there to celebrate a life lived well and taken too soon.

The 70-year-old church swayed with psalm, hymn, and gospel; with the “Ave Maria”; with voices of youngsters struggling to sing for their classmates Christine and Elaine, who had been scheduled to start third and fourth grade at St. Theresa’s grammar school, 50 yards away.

Larry Reynolds stood in the choir loft, high above the congregation. With strong, rough carpenter’s hands, he gently held a fiddle and began to play “The Culan,” a 400-year-old Gaelic song. As communion commenced below, each of his notes echoed a tear throughout the immense stone building.

Reynolds himself is from the County Galway village of Ahascragh. He has known both families, the Beattys and the Devanes, for 30 years, and after he finished, Mary Twohig, a nursing school classmate of Mary Devane, walked slowly to the podium to recite “A Nurse‘s Prayer” and share an elegant eulogy with all those devastated by these three deaths.

Then, the Mass ended. Incense caressed the air as the pallbearers retreated through the church and out to those hearses idling at the curb before the big crowd drove off in thick traffic for the sad trip to St. Joseph’s Cemetery, where Mary Beatty Devane and her two precious little girls were set to final rest, three members of a truly royal family.

MIKE BARNICLE

BOSTON GLOBE

July 31, 1997

As soon as everyone had gathered in St. Ignatius Church at Chestnut Hill yesterday for the funeral Mass, a full company of Jesuits marched silently down the center aisle of the handsome stone edifice to bury a brother, Rev. Ray Callahan, SJ, who fell dead at his desk last week at 59. Until his death, Father Callahan had been president of Nativity Prep in Roxbury, a miracle of the city where children are given the gift of a future.

It was 10 a.m. when the Jesuits took their seats directly across the aisle from Marie Callahan, the deceased priest’s mother, who sat sadly with her daughters. She wore a black dress and held a single white rose Outside the church, the sun stood sentry in a cloudless sky and a wonderful breeze danced across the day. Inside, people stood shoulder to shoulder singing “Here I am, Lord” as five Jesuits began the beautiful ceremony.

There were no TV cameras or any reporters clamoring for participants to discuss the quiet, noble life of Ray Callahan, who never sought a headline. He was born in Framingham, son of a newspaperman, and he went to Fairfield University until God tapped him on the chest with such ferocity that he chose the Marine Corps of Catholicism — the Jesuits — as a life.

He taught at Boston College as well as at BC High, but for the past several years he had run Nativity Prep. It is a small, private school — 15 students in 4 grades, 5 through 8 — where boys from places like Mattapan, Roxbury, and Dorchester get just about the finest free education around.

“Anybody can learn math,” Ray Callahan used to say, “but our job is to help these boys gain pride and dignity, too. They are wonderful, strong children.”

All this week, the town has witnessed a flood of publicity concerning the future of William Weld. And as the funeral began, a new governor, Paul Cellucci, was in the State House discussing tax cuts and judgeships. All of it is considered news because these people and their policies affect so many.

However, Ray Callahan was a single man who touched a thousand lives. He was a Jesuit priest who had a hand on someone’s shoulder every single day, pushing or prodding them toward heights once thought to be unattainable.

As Rev. William Russell, SJ, delivered the homily, one of the many Nativity Prep students at Mass bowed his head in grief. His name was Adrian Rosello. He is a 13-year-old from Mattapan who will be in eighth grade this September.

“I never expected him to die,” Rosello said quietly. “I loved him. He always made me laugh and told me I could do better. He believed in me. How could he die in the summer?”

Now, at Communion, Mike Burgo came from the sacristy holding a guitar. He began to sing the infectious hymn “Be Not Afraid” and soon the huge congregation joined Burgo, the sound of their grateful voices filling the church and spilling out toward the trolley tracks and the campus of Boston College.

“You shall cross the barren desert, but you shall not die of thirst. You shall wander far in safety, though you do not know the way. You shall speak your words in foreign lands, and all will understand. You shall see the face of God and live.

“Be not afraid. I go before you always.”

Both song and service are part of the constant comfort of Catholicism, a religion that blankets the start and conclusion of life with splendid ritual. But Ray Callahan represented the finest aspects of his faith every single day. He led by example, a humble man dedicated to God and to education.

And yesterday his legacy filled St. Ignatius: Former students; young people like Amy Shields, who went straight from Duke to teaching at Nativity Prep because providing a child with the excitement of ideas is far more rewarding than making money; hundreds of friends; and his fellow priests.

Then the Mass ended and the Jesuits filed out to the front of the church where they stood in a circle on the sidewalk, resplendent in white cassocks, as six Nativity Prep boys carried a black casket down gray cement steps. They were followed by Marie Callahan, who walked slowly out of the church into the bright sun of a day, comforted by the knowledge that while others elsewhere celebrated temporal rewards of prosperity or politics, the crowd around her had gathered to celebrate the rich and marvelous life of Raymond J. Callahan, SJ.

“Thank you for your son,” Rev. William Leahy, the president of Boston College, said to Marie Callahan.

“Thank God for my son,” his mother replied.

BOSTON GLOBE

June 15, 1997

So here she came the other day, walking through the haze of a humid afternoon, walking proudly up Adams Street in Dorchester past a line of red brick rowhouses where children sat on stoops seeking relief from the heat, walking right into a future filled now with potential due to her own diligence.

Her name is Phong Tran and she is 17 and she has only been in the United States since 1991 — time enough, though, to finish at the top of her Cathedral High class and win a four-year scholarship to UMass-Amherst, where she will be one more Vietnamese student representing the constant American spirit of renewal “It is like a dream,” Phong Tran pointed out. “I am so grateful. I am so happy.”

“With no scholarship, where would you go?” she was asked.

“To work,” Phong Tran replied.

“What do you want to be?”

“A doctor,” she said right away. “So I can help others. So I can repay people for my good fortune.”

The young woman earned her fortune all by herself. And she is only one of 83 premier students from across the state who have been granted a gift worth $8,000 a year simply because they were smart enough to be smart.

The University Scholars program is a new benefit provided by the state’s university system. This year, four-year scholarships were offered to those seniors who finished first or second in their classes at each of Massachusetts’ 400 public and private high schools. Tomorrow, many of the 83 who accepted the scholarships will be honored at a State House reception.

For decades, the UMass system has been smeared by elitists and relegated to second-class status in a commonwealth that boasts a long line of more famous and more expensive private institutions. But, whether at Harvard or UMass-Lowell, nobody is ever given an education, only the opportunity to get one — grab one, really — and that chance is not lost on those students and families going now for free.

“My daughter is very ambitious,” the Rev. Earl McDowell was saying Friday. “We teach all our children to be ambitious, to have goals and go after them. She did, too.”

Rev. McDowell was sitting in the second-floor parlor of his Roxbury apartment along with his wife, Patricia. The two parents were crazy with pride over their daughter Valerie, who topped the ticket at Madison Park High and will be going to UMass-Boston in September. Both young women — Phong Tran from Vietnam and Valerie McDowell from Guild Street — take a splendiferous spirit off to their amazing new world.

“She just graduated last night,” Patricia McDowell explained. “She was the valedictorian. The ceremony was at Matthews Arena, and she walked in with all the dignitaries.”

“I had tears in my eyes,” her husband added.

“She’s the first in our family to ever go to a four-year college,” the mother said.

“She worked hard for it,” Rev. McDowell said. “She had three part-time jobs all year, too. This scholarship is a true blessing because, as you can see, I took a vow of poverty.”

“He took it seriously, too,” his wife laughed.

“Valerie has always been a straight-A student,” the proud father continued. “At the Nathan Hale. At the Wheatley and all through Madison Park. We are firm believers in public education, but it’s a matter of determination and parental involvement whether your children do well.

“It’s not up to society, to the city, or to the police to provide children with goals and ambitions. It’s up to us as her mother and father,” Rev. McDowell stated. “If a black youth is nothing, it means they chose to be nothing.”

“Basically, we have tried to be our daughter’s best friends as well as her parents,” Patricia McDowell added. “It’s good that way. We were able to guide her away from trouble, and if our children meet someone not up their standards, we let them know. And they just say `goodbye.’ “

Now, the valedictorian from the night before was ready to go to work on the morning after her triumph. Valerie McDowell, symbol of any future we might have, is a marvelous young woman who only dreamed of a university education prior to the gift of a four-year scholarship.

But sometimes dreams come true. And sometimes hard work, discipline, and dedication are rewarded, and when that happens, the grateful — like Valerie McDowell and Phong Tran — head to college, two magnificent investments in a state of mind.

BOSTON GLOBE

June 8, 1997

Orla Benson, murdered on Sept. 23, 1995, in an Allston playground, was young and alive again Friday as her biographer discussed her wonderful life in glowing terms while a Suffolk Superior Court jury was being selected to try the man charged with her killing. Benson had come from Ireland that summer to work when she was raped and stabbed to death by a degenerate who left her dead in the dark on the steps of Ringer Park.

“Orla was a nice girl,” Thomas O’Leary was saying. “She was young and pretty and totally innocent. And she had just spent the happiest night of her life in Boston when this happened. She would have graduated from college that fall “She was out with about 30 friends. They had been to South Boston, to Cambridge, to Brighton. They rented a trolley for a party to celebrate a girl’s wedding, and they were going home to Ireland in a few days. She was 50 yards from her apartment.”

O’Leary today is Orla Benson’s voice, her best friend in court. He is a sergeant of police with the Homicide Unit, and his duty since early in the day that Sept. 23 has been to bring her killer to court and help deliver some measure of justice to her horribly wounded family.

It is always an event of tremendous significance, the murder of a human being. And whether it is multiple counts, as in Oklahoma City, or a single victim, the word “closure” becomes something for glib psychiatrists or talk-show callers because the pain of survivors is of such depth and duration that it simply becomes part of their own existence.

“Plenty of sleepless nights over this one,” O’Leary said. “I can see her sometimes. I know her.”

In the courtroom, Benson’s father, Tom, an engineer from Killarney, sits daily not 10 feet behind Tony Rosario, a convicted rapist who is accused of forever silencing the sounds of Tom Benson’s only daughter’s life. The elder Benson is of slight build and has a soft spring rain of a smile and gentle blue eyes permanently dulled by this inexcusable death.

Rosario is 29 now. He was born in New York and brought up in Boston, where he was a menace. All last week, he wore a blue sweatshirt, black pants, black sneakers, leg irons and no hint of expression on a face unfamiliar with remorse as he listened to pretrial arguments of the prosecutor, James Larkin, and the objections of his own gifted appointed counsel, Roger Witkin, in the third-floor room where a panel of citizens will address the brutality of Orla Benson’s murder.

Rosario is a living advertisement for the flaws of a system where a single bureaucratic error can result in a monstrous evil being committed. In 1991, he was convicted of raping and beating a woman at the Forest Hills T station. He got 10 years but was out two years later.

Free on probation, he was arrested on April 24, 1994, for raping a 14-year-old runaway at knifepoint after she fled, naked, from his car. But the runaway kept right on running and would not testify, so Rosario went unconvicted.

He was indicted for unarmed robbery in Cambridge, but somehow never had his probation revoked. Then on July 31, 1995, seven weeks before Orla Benson died, Rosario was grabbed for the rape of a 15-year-old special needs student in Brighton. She had been working for Rosario, who had, quite amazingly, been hired by the city’s Parks and Recreation Department to boss teenagers retained for a summer of cleaning playgrounds.

“He told her unless she had sex with him, she wouldn’t get paid,” a lawyer familiar with the case of the special needs student said, adding that Rosario took her to his apartment on Glenville Avenue in Allston “and told her: No sex, no check. But, because she was retarded, he beat it.”

“He never should have been out,” Tom O’Leary said. “The system took a hit for him being on the payroll. Probation took a hit, too. But Orla took the biggest hit of all.”

Thursday, Rosario had an opportunity for minimal decency when he accepted, then reneged, on an agreement that had him pleading guilty to first-degree murder. But lunch with jailhouse lawyers, along with success in beating the system and making a sad joke of probation, caused him to change his mind.

So Tom Benson and his family will be forced to endure a trial where his daughter will die again; a trial where judge and jury will surely see in the testimony offered that this world needs people like Orla Benson as much as it needs a sunrise, because her biographer remains on the case, insistent on delivering his message.

“I know her,” said Sergeant Thomas O’Leary. “She was a wonderful girl.”

BOSTON GLOBE

March 27, 1997

One of the babies who represents the future for these young girls pushing a carriage instead of carrying books was being wheeled down Mercer Street in South Boston yesterday by her mother, who is not quite 17. The mother was white and the infant a wonderful shade of mocha, which sure made her beautiful but appears not to have inspired much glee in the household where she is being raised.

“My boyfriend’s black,” the girl pointed out. “And my mother hates him. She don’t hate the baby, but she hates what happened, you know In projects like D Street and Old Colony, there seems to be a significant increase in the number of interracial infants born to white teenagers. Many of these girls drop out of school prior to giving birth and try to raise their own baby in the same apartment where they had been attempting to grow up when a pregnancy interrupted the process.

“There are quite a few white girls having babies with black and Hispanic guys here,” one of the police who specializes in South Boston project life was saying yesterday. “It’s a good news-bad news story: The good news is that race is not the factor in these kids’ lives that it was — and is — for a lot of their parents. Kids don’t have the same hangups as adults. Kids don’t go around talking about what busing did to their town. That was 20 years ago. They weren’t even born.

“The bad news is it means the end of the line for the girl: dropping out of school, no job, raising a kid where her mother, father, too, if he’s around, can’t stand looking at the baby because the baby’s not white.”

Yesterday, the girl pushing the stroller had a plan: She intended to walk to Rotary Variety for milk and then visit a friend on Silver Street. Her plan was built around the premise that she should try to remove herself and her child from the apartment for at least five hours. Kind of like a job.

For some, the increase in interracial children represents another assault on “The Town.” South Boston has been staggered by suicide and drugs. One — kids killing themselves — is a shock. The other — cocaine and heroin — is an old habit, narcotics having been easily available there for a long time.

At a community gathering the other evening, a suggestion was made that more police were needed to fight drugs and restore the mythic sense of “neighborhood.” But the statement was made in a section of the city no longer immune to social conditions that cause deterioration: alcoholism, addiction, AIDS, teenage pregnancy, illiteracy, poverty, unemployment, fractured families and rampant rates of divorce or abandonment.

Yet police alone cannot do the job. Nor can schoolteachers, priests or social workers. The type of work necessary can only be accomplished by a parent, and in the projects of South Boston, like projects everywhere, too many parents are poor or ill-equipped for the task or juveniles themselves or AWOL from responsibility. To ignore this is ludicrous.

“It’s a bizarre form of equality,” the police officer was saying. “And it’s filled with irony. Many of the white kids in D Street or Old Colony are in the same position as a lot of black kids in Roxbury and Dorchester: They have no shot and they know it by the time they’re 15.

“They’re poor. For a lot of them, there isn’t a parent around. They don’t go to school, so they do whatever is free and feels good.

“Now what can 100 more cops do about that? We can patrol. We can investigate. We can arrest. We can get a warrant and go in an apartment but we cannot go inside someone’s head and force them to change their behavior.

“And it’s not just cocaine taking a toll on South Boston. Look around and you will see more bars, taverns and package stores in this community, per capita, than probably anyplace else in the city. You fall down drunk and people think it’s funny, actually kind of normal. You overdose and it’s a tragedy, but they are both addictions and there are plenty of addicts to go around in this town.”

Still, some in South Boston seem amazed at the ages of the desperate or those already dead by their own hand. And the enormity of the problem is such that others either refuse to recognize it or mistakenly feel that it is restricted to project life where a baby can face a bleak future because its very existence serves as a reminder of failure rather than a source of joy.