With husband Bob, Myra Kraft attended many fund-raisers, smiling and greeting donors. (1997 File/The Boston Globe) |

Deadline Artists: America’s Greatest Newspaper Columns

Edited by John Avlon, Jesse Angelo & Errol Louis

At a time of great transition in the news media, Deadline Artists celebrates the relevance of the newspaper column through the simple power of excellent writing. It is an inspiration for a new generation of writers—whether their medium is print or digital-looking to learn from the best of their predecessors.

This new book features two of Mike’s columns from The Boston Globe. The book says, “Barnicle is to Boston what Royko was to Chicago and Breslin is to New York—an authentic voice who comes to symbolize a great city. Almost a generation younger than Breslin & Co., Barnicle also serves as the keeper of the flame of the reported column. A speechwriter after college, Barnicle’s column with The Boston Globe ran from 1973 to 1998. He has subsequently written for the New York Daily News and the Boston Herald, logging an estimated four thousand columns in the process. He is also a frequent guest on MSNBC’s Morning Joe as well as a featured interview in Ken Burns’s Baseball: The Tenth Inning documentary.”

Read the columns here (you can buy the book by clicking here)

“Steak Tips to Die For” – Boston Globe – November 7, 1995

Those who think red meat might be bad for you have a pretty good argument this morning in the form of five dead guys killed yesterday at the 99 Restaurant in Charlestown. It appears that that two late Luisis, Bobby, the father, and Roman, his son, along with their three pals, sure did love it because there was so much beef spread out in front of the five victims that their table-top resembled a cattle drive.

“All that was missing was the marinara,” a detective was saying yesterday. “If they had linguini and marinara it would have been like that scene in The Godfather where Michael Corleone shoots the Mafia guy and the cop. But it was steak tips.”

Prior to stopping for a quick bite, Roman Luisi was on kind of a roll. According to police, he recently beat a double-murder charge in California. Where else?

But that was then and this is now. And Sunday night, he got in a fight in the North End. Supposedly, one of those he fought with was Damian Clemente, 20 years old and built like a steamer trunk. Clemente, quite capable of holding a grudge, is reliably reported to have sat on Luisi.

Plus, it is now alleged that at lunch yesterday, young Clemente, along with Vincent Perez, 27, walked into the crowded restaurant and began firing at five guys in between salads and entrée. The 99 is a popular establishment located at the edge of Charlestown, a section of the city often pointed to as a place where nearly everyone acts like Marcel Marceau after murders take place in plain view of hundreds.

Therefore, most locals were quick to point out that all allegedly involved in the shooting—the five slumped on the floor as well as the two morons quickly captured outside—were from across the bridge. Both the alleged shooters and the five victims hung out in the North End.

However, yesterday, it appears, everyone was playing an away game. For those who still think “The Mob” is an example of a talented organization capable of skillfully executing its game plan, there can be only deep disappointment in the aftermath of such horrendous, noisy and public violence.

It took, oh, about 45 seconds for authorities to track down Clemente and Perez. Clemente is of such proportions that his foot speed is minimal. And it is thought that his partner Perez’s thinking capacity is even slower than Clemente’s feet.

Two Everett policeman out of uniform—Bob Hall and Paul Durant—were having lunch a few feet away from where both Luisis and the others were having the last supper. The two cops have less than five years’ experience combined but both came up huge.

“They didn’t try anything crazy inside. They didn’t panic,” another detective pointed out last night. “They followed the two shooters out the door, put them down and held them there. They were unbelievably level-headed, even when two Boston cops arrived and had their guns drawn on the Everett cops because they didn’t know who they were, both guys stayed cool and identified themselves. And they are going to make two truly outstanding witnesses.”

The two Boston policemen who arrived in the parking lot where Clemente and Perez were prone on the asphalt were Tom Hennessey and Stephen Green. They were working a paid detail nearby which, all things being equal, immediately led one official to cast the event in its proper, parochial perspective: “This ought to put an end to the argument to do away with paid details,” he said. “Hey, ask yourself this question: You think a flagman could have arrested these guys?”

The entire event—perhaps four minutes in duration, involving at least 13 shots, five victims and two suspects caught—is a bitter example of how downsizing has affected even organized crime. For several years, the federal government has enforced mandatory retirement rules—called jail—on several top local mob executives.

What’s left are clowns who arrive for a great matinee murder in a beat-up blue Cadillac and a white Chrysler that look like they are used for Bumper-Car. The shooters then proceed to leave a restaurant filled with the smell of cordite and about 37 people capable of picking them out of a lineup.

“Part of it was kind of like in the movies, but part of it wasn’t,” an eyewitness said last night. “The shooting part was like you see in a movie but the fat guy almost slipped and fell when he was getting away. That part you don’t see in a movie. But what a mess that table was.”

“We have a lot of evidence, witnesses and even a couple weapons,” a detective pointed out last evening. “But the way things are going in this country it would not surprise me if the defense argues that they guys were killed by cholesterol.”

“New Land, Sad Story” – Boston Globe – November 23, 1995

Three Cadillac hearses were parked on Hastings Street outside Calvary Baptist Church in Lowell Tuesday morning as an old town wrestled with new grief. Inside, the caskets had been placed together by the altar while the mother of the dead boys, a Cambodian woman named Chhong Yim, wept so much it seemed she cried for a whole city.

The funeral occurred two days before the best of American holidays and revolved around a people, many of whom have felt on occasion that God is symbolized by stars, stripes and the freedom to walk without fear. But a bitter truth was being buried here as well because now every Cambodian man, woman and child knows that despite fleeing the Khmer Rouge and soldiers who killed on whim, nobody can run forever from a plague that is as much a bitter part of this young country as white meat and cranberry sauce.

The dead children were Visal Men, 15, along with his two brothers Virak, 14, and Sovanna, 9, born in the U.S.A. They were shot and stabbed last week when the mother’s friend, Vuthy Seng, allegedly became enraged at being spurned by Chhong Yim, who chose her children over Seng.

There sure are enough sad stories to go around on any given day. However, there aren’t many to equal the slow demise of a proud, gentle culture—Cambodian—as it is bastardized by the clutter and chaos we not only allow to occur but willingly accept as a cost of democracy.

The three boys died slowly; first one, then the other in a hospital and, finally, the third a few days after Seng supposedly had charged into the apartment with a gun and a machete. He shot and hacked all three children along with their sister, Sathy Men, who is 13 and stood bewildered beside her howling mother, the two of them survivors of a horror so deep their lives are forever maligned.

At 10:45, as the funeral was set to begin, two cops on motorcycles came up Hastings ahead of a bus filled with children from Butler Middle School. The boys and girls walked in silence into the chapel to pray for the dead who have left a firm imprint on their adopted hometown.

The crowd of mourners was thrilling in its diversity. There were policemen, firefighters, teachers and shopkeepers. The young knelt shoulder-to-shoulder with the old. There were Catholic nuns and Buddhist priests. There were friends of the family as well as total strangers summoned only by tragedy.

A little after 11 a.m., Hak Sen, who drove from Rhode Island, parked his car by the post office and headed toward Calvary Baptist Church.

“I am late. I got lost,” Hak Sen said.

“Are you a friend of the family?” he was asked.

“No,” he replied. “I do not know them. I come out of respect and sadness. We all make a terrible journey to come here to America and this is very, very bad.”

Hak Sen said he and his family were from Battambang Province, along the Thai-Cambodian border. He said that he served in the army before Pol Pot took over his country and that he and his family were forced to flee but not all made it to the refugee camps.

“I am lucky man,” Hak Sen pointed out. “I survive. My wife, she survive and two of our children, they survive.”

“Did you lose any children?” he was asked.

“Yes,” he said. “I lost three boys, just like this woman. Three boys and our daughter. They all dead. The malaria killed them in the jungle. There was not enough food and no water and they were young and could not fight the disease and they died. They all dead. My mother and father too.”

The innocent children inside the church as well as the big-hearted citizens of Lowell along with the majority of people who will buy a paper or carve a turkey today simply have no idea of the epic, tragic struggle of the Cambodians. They left a country where they were killed for owning a ballpoint pen or wearing a pair of eyeglasses to arrive in this country where, each day, we become more and more narcoticized by the scale of violence around us.

At the conclusion of the service, Lowell detectives Mike Durkin, John Boutselis and Phil Conroy helped carry the caskets to the hearses. The procession wound slowly through city streets, pausing for a few seconds outside the Butler School, where pupils lined both sides of the road like grieving sentries as the entourage entered Westlawn Cemetery.

“This is as sad as it gets,” said Roger LaPointe, a cemetery worker. “We cut the first two graves the end of last week but the funeral director told us we better hold on. When the third boy died, we had to cut it some more. It’s an awful thing. That hole just kept getting bigger.”

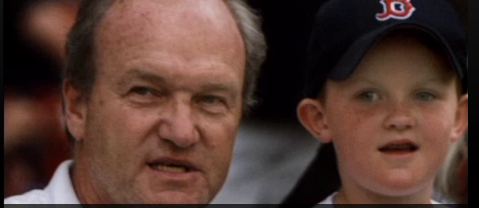

With husband Bob, Myra Kraft attended many fund-raisers, smiling and greeting donors. (1997 File/The Boston Globe) |

She was the conscience and soul of the Patriots, a woman who came to football reluctantly, through marriage, then used the currency of football fame to enhance her lifelong missions of fund-raising and philanthropy.

“Without Myra Kraft, it’s quite possible we’d be going to Hartford to watch the Patriots,’’ former Globe columnist Mike Barnicle said yesterday after it was announced that Myra succumbed to cancer at the age of 68. “Obviously, Bob Kraft has deeps roots in this area, but Myra was so much a part of this community – the larger community beyond the sports world – she was never going to allow her husband to leave.’’

We all knew Myra was failing in recent years, but she never wanted it to be about herself. Through the decades, thousands of patients were treated at the Kraft Family Blood Donor Center at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, but when Myra got cancer there was no announcement; instead, the Krafts announced a $20 million gift to Partners HealthCare to create the Kraft Family National Center for Leadership and Training in Community Health.

It was always that way. You’d go to a fund-raiser and Myra would be standing off to the side with Bob, smiling, greeting donors, and gently pushing the cause of the Greater Good. They were married for 48 years and had four sons who learned from their mom that more is expected of those to whom more is given.

It’s fashionable to enlarge the deeds of the dead and make them greater than they were in real life. This would be impossible with Myra Kraft. She was the real deal. Myra Hiatt Kraft was a Worcester girl, a child of privilege, and she spent her life giving back to her community.

Not a sports fan at heart, Myra was a quick study when Bob bought the team in 1994. Sitting next to Bob and eldest son Jonathan, she learned what she needed to know about football. When something wasn’t right, she spoke up. Myra disapproved when the Patriots drafted sex offender Christian Peter in 1996. Peter was quickly cut. She objected publicly when Bill Parcells referred to Terry Glenn as “she.’’ Like Parcells and Pete Carroll before him, Bill Belichick operated with the knowledge that Myra was watching. Keep the bad boys away from Foxborough. Don’t sell your soul in the pursuit of championships.

The base of Myra’s philanthropic works was the Robert K. and Myra H. Kraft Family Foundation. The Boys & Girls Clubs of Boston were a particular passion. Among its other missions, the Kraft Foundation endowed chairs and built buildings at Brandeis, Columbia, Harvard, BC, and Holy Cross.

BC and HC are Jesuit institutions. Myra Kraft was Jewish and worked tirelessly for Jewish and Israeli charities, but that didn’t stop her from helping local Catholic colleges.

“She was the daughter of Jack [Jacob] and Frances Hiatt,’’ Father John Brooks, the former president of Holy Cross, recalled. “Jack was a great benefactor of Holy Cross. He was on our board and was a very important person to the city of Worcester. I was a regular attendee of the annual Passover dinner at the Hiatt home when Myra was still living in Worcester. What struck me about Myra was that she was very proud and was a wonderful mother to her four boys.’’

During the 2010 season, Myra steered the New England Patriots Charitable Foundation toward early detection of cancer. Partnering with three local hospitals, the Krafts and the Patriots promoted the “Kick Cancer’’ campaign, never mentioning Myra’s struggle with the disease.

Anne Finucane, Bank of America’s Northeast president, held a large Cure For Epilepsy dinner at the Museum of Fine Arts last October and recalled, “Myra showed up at our event even though she was battling her illness and they were in the middle of their season. That’s the way she was. She could come and see you and make a pitch on behalf of an organization. There are people who just lend their name and then there are people who take a leadership role to advance an issue. She was a pretty good inspiration for anyone in this city.’’

Just as it’s hard to imagine the Patriots without Bob Kraft, it’s impossible to imagine Bob without Myra. After every game, home or away, win or lose, Myra was at Bob’s side, waiting at the end of the tunnel outside the Patriots locker room.

We miss her already.

Dan Shaughnessy is a Globe columnist.

Globe Columnist

July 20, 2011

Next time you feel like ripping Terry Francona, try to remember that the man has a lot on his mind. The manager’s son, Nick Francona, a former pitcher at the University of Pennsylvania, is a lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps, serving a six-month tour, leading a rifle platoon in Afghanistan. Twenty-six-year-old Nick is one of the more impressive young men you’ll ever meet. In a terrific piece for Grantland.com, Mike Barnicle asked Terry Francona how’s he doing as the dad of one of our soldiers at war. “I’m doing awful,’’ answered the manager. “My wife’s doing worse. I think about it all the time. Worry about it all the time. Hard not to. Try and stay away from the news about it. Try not to watch TV when stories about it are on, but it’s there, you know? It’s always there.’’

Two Interviews. Hard questions. Figuring out the partnership of Terry Francona and Theo Epstein, one of the most successful collaborations in baseball.

He is wearing white uniform pants, a red hot-top and black spike-less athletic shoes, a Red Sox cap on his hairless head. And he is staring at a cluster of numbers on the screen of a laptop. The numbers run alongside the names of those players who are in the starting lineup of the Baltimore Orioles, the Friday night game about four hours away. The numbers are mathematical guidelines to the recent baseball past: What Baltimore players did against Red Sox pitchers. Where players are most likely to hit the ball if they connect with a curve, a slider, or a cut fastball.

“Can’t call ’em stat-geek stuff,” Tito Francona volunteers. “That’s disrespectful. There’s a lot of good information here, matchups, stuff like that. People work hard at this.

“I used to do these by hand,” he says. “Did it before all this math stuff and computers got so big. Did it without knowing it. When I managed the Phillies. Did ’em all by hand then. Would sit down with a pencil and a piece of paper and go through opposing lineups. Took forever. Now it’s all on these things, computers.

“And I suck at computers,” he is saying. “I’m a one-finger guy with them. I can get around on a computer OK using one finger but it’s not my favorite thing.”

“How you doing otherwise?” he is asked.

“Exhausted,” he replies.

“How’s Nick doing?”

“He’s OK,” said the Red Sox skipper, now in his eighth summer of employment with a club that dominates daily discussion in New England. “Guys in his squad in front of him on patrol got hit the other day. Tough day for him. Good thing though, he loves what he’s doing.”

The father now talking about the son: 26-year-old Lt. Nick Francona, United States Marine Corps, halfway through a six-month, one-day tour leading a rifle platoon in a long war that has forever ravaged a country locked somewhere in centuries past, Afghanistan.

“You OK?”

“Awful, ” the manager says. “I’m doing awful. My wife’s doing worse. I think about it all the time. Worry about him all the time. Hard not to. Try and stay away from the news about it. Try not to watch TV when stories about it are on, but it’s there, you know? It’s always there.”

The phone on his desk rings and Francona reaches to answer with his left hand, the right-hand index finger slowly scrolling through the Orioles roster on his laptop, his eyes narrowing behind glasses, looking, always looking for an edge.

“Yeah Theo, what’s up?” he says, pausing to listen to the guy on the line, Theo Epstein, the 37-year-old general manager.

“Yeah, I spoke to Buck Showalter about that … OK … Talk to you later.”

“Theo,” Francona says, hanging up, a smile creasing his weary face. “How do we get along? We got through eight years here together. We haven’t killed each other. I’d say we get along pretty good.”

The Major League Baseball season runs from early February, across spring, through summer, and concludes for most players and teams just as Columbus Day approaches. The season, longest of all the majors and quite exhausting, is a bit like dating a nymphomaniac; it demands daily performance. And in Boston the expectation is always to play toward Halloween.

In some aspects the game has changed irrevocably since a young Tito Francona, his father’s first baseman’s mitt on his hand, ran to sandlots in the small Pennsylvania town where his family lived. Managers today are provided tools to compete that were simply not available 20, even 10 years ago. They have access to a Niagara of information sometimes spoon-fed by a generation of front-office young people who have rarely played actual games.

“People, some writers I guess, get that wrong you know,” Tito Francona points out. “Theo and the guys working for him, they’re not in here six times a day with stats telling us what to do. We get stuff before a series begins and it’s valuable. I study it. I do.

“But it’s about more than numbers,” he says. “I remember a few years ago, we’re playing the Yankees on national TV and one of the kids in baseball ops — he’s not here now — says to me about five hours before the game, ‘You got Mike Lowell in the lineup?’ And I say, ‘Yeah.’ And he says he doesn’t do well in the matchup with Chien-Ming Wang, who was pitching for the Yankees.

“I say to the kid, ‘So you don’t want me to play him?’ And he says, ‘Yeah’ and I tell him, ‘OK. Look over there. There’s Mikey Lowell’s locker. He’s over there. You go tell Mikey Lowell he’s not playing in a national TV game against our biggest rival ’cause your fucking numbers tell us not to play him. See what kind of reaction you get from him and then come back and tell me.’ Course Mikey Lowell played that game.

“That doesn’t happen a lot, though. It works pretty well, the numbers stuff and us down here.”

“What are the biggest differences between you and Theo?” Francona is asked.

“There aren’t a whole lot,” he answers. “We talk every day. It’s good. We’re not yelling ‘Shut the fuck up’ at each other either. He knows I value the input I get from him and the guys in baseball ops, but he knows my world down here in the clubhouse is different from theirs.

“I get it. He knows I get it. And he knows getting a player in winter is different from getting a guy ready in the seventh inning. In uniform you’re looking at today. Right now.”

Two different worlds. Francona and Epstein. They are characters out of a kind of baseball version of Upstairs-Downstairs the old PBS series about class and expectation. One is Ivy League. The other is Summer League. One grew up dreaming of baseball. The other played it, raised in a house with a father who made a living at it in the major leagues.

Terry Francona is 52 years old, a baseball lifer from New Brighton, Penn., where the median annual family income today is roughly $31,000. The town is 30 miles northwest of Pittsburgh, and it is a place where men worked factory jobs and women knew how to stretch every grocery dollar, day to day, week to week. He went to high school there, attended the University of Arizona, was a 1980 first-round draft choice by the Montreal Expos.

Theo Epstein, 37, grew up in Brookline, Mass., median annual family income, $120,000, in the shadow of Fenway Park. He went to Yale, was sports editor of the Yale Daily News, got a job as a summer intern with the Orioles, parlayed his energy and his instincts into a front office position with the San Diego Padres, came home to Boston when John Henry, Tom Werner, and Larry Lucchino purchased the Red Sox in 2001. Took over as general manager in 2003, a lifelong dream in his back pocket at age 29.

The other day Epstein was sitting in a conference room located in the bowels of the ballpark, in a space that used to be part of an old bowling alley before it and much of the rest of Fenway was renovated and rebuilt under the watchful eye of Lucchino and ballpark architect Janet Marie Smith. He is a confident, disciplined, self-contained young guy, cautious with language and body movement, always alert that in the crazed media atmosphere that surrounds the Red Sox, one dropped syllable or the wrong adjective could put thousands of talk-show callers into crisis mode. In addition to statistics, the semantics of baseball have changed, too, young front-office people far less reliant on one of the locker-room staples of the game: The F-Bomb.

“What do you think Tito said about you?” I ask Epstein.

“Ahh,” he says, “he probably said we worked really well together. That we understand each other and respect the differences between our two jobs, and that he knows I have his back.

On the walls of the conference room were several white-boards filled with names of high school and college players just drafted, along with others to be looked at in fall ball leagues. The future hanging right there. The immediate, game no. 89 on the march to 162, four hours away.

“Actually we’re like an old married couple,” Epstein adds. “I can usually tell from his facial expression what kind of mood he’s in. And there is an element of ‘his’ world versus ‘my’ world in the relationship, but we’ve learned to pick our battles, and as well as I know him he knows me too.

“Communication is different in the clubhouse than it is in a boardroom. The heartbeat that exists in the clubhouse … you don’t find that same type of heartbeat in the front office. There is a cloak of intensity in the clubhouse that doesn’t exist here,” the general manager points out. “There is a little more objectivity here in this office. We see the game at 10,000 feet. Tito sees it 50 feet away. Tito is looking at tonight’s game and those of us in baseball ops, a lot of the time, are looking at the next five years.

“His job is clear: Win tonight’s game. That’s his focus. Ours is that, as well, but the focus is also on the years ahead. That’s the inherent conflict between the two jobs, his and mine. It’s the subjective versus the objective.”

“What did you want to know from him when he interviewed for the job?” Theo Epstein is asked.

“That’s interesting,” he replies. “The big thing was what kind of relationship would exist? Would both of us be willing to say anything to the other without worrying about hurting feelings?”

“Right before I interviewed for the job with Theo, I called Mark Shapiro of the Indians. He’s one of my best friends in baseball and I asked him what I should do,” Tito Francona was saying earlier. “He gave me good advice I still use today. Mark told me, ‘Just don’t try and bullshit him.'”

“It’s become like a family relationship,” Epstein says. “You can’t bury things. We get them out in the open. I recognize the limitations of my view and my background but the two of us work well together.”

Epstein had just returned from lunch with his father, Leslie Epstein, who retired as head of the creative writing department at Boston University. The day before, a 39-year-old Texas firefighter sitting at a Rangers game alongside his 6-year-old son had died after falling out of the stands in pursuit of a foul ball tossed toward him as a generous gesture by Texas outfielder Josh Hamilton.

A dad’s dying young, at a ballpark, his little boy bearing eternal witness, clearly touched Epstein. He is sometimes labeled as cold and impersonal in his approach to whom he wants on or off his roster and what his club’s needs are, but what took place in Texas clearly triggered a reality he knows well: He is a young man living a dream.

“When I heard about that I wanted to have lunch with my dad,” Theo Epstein says. “What an awful story.”

In the manager’s office, Francona, his son Nick constantly on his mind, was attempting to lose himself in the landscape of a baseball game about to be played with the Baltimore Orioles.

“Theo knows,” Francona says with a slight laugh. “He knows he’s already looking at next year’s draft and he knows I’m down here looking at the seventh inning tonight. That’s the game.”

Mike Barnicle is an award-winning journalist. This is his first article for Grantland.

Mar. 1, 2011

BOSTON — The Harvard community — and people the world over — is mourning the death of Reverend Peter Gomes, the man who ran the university’s Memorial Church for over forty years.

Gomes died Monday night because of complications from a stroke he had in December. He was 68.

|

| The Reverend Peter Gomes died Monday at the age of 68, after a more-than 40-year ministry at Harvard University. |

Gomes’ longtime friend, writer and columnist Mike Barnicle, met Gomes because the two would regularly spend early mornings at the same restaurant. “He was an education to sit with, next to, to listen to, a sheer education. Not just in terms of his moral values but his view on the world,” Barnicle told WGBH’s Emily Rooney on Tuesday.

A black, openly gay minister, Gomes was a decided rarity. He came out about his sexuality in 1991.

He was also politically conservative for most of his career, although he changed his political affiliation to Democrat to vote for Gov. Deval Patrick in 2006.

Barnicle said Gomes learned from his own experience being different, and set out to help others with theirs.

“He was was an expert at honing in on the demonization of people,” Barnicle said. “He could see people and institutions being demonized well before it would become apparent tthat they were being demonized.”

That, Barnicle said, gave Gomes a sense of fairness that underguarded his political and religious beliefs.

“It’s not fair to go after people because of who they are, or because of their sexual orientation, or because of their color, or because of their income, or because of their zip code. That’s who he was, he was an expert in what’s fair,” Barnicle said.

Gomes was known for his soaring, intricate speaking style. “I like playing with words and structure,” he said once, “Marching up to an idea, saluting, backing off, making a feint and then turning around.”

“His sermons were actually high theater in my mind,” Barnicle remembered.

Gomes did not leave behind a memoir; He said he’d start work on it when he retired, at 70. It’s a shame, Barnicle said. “We need more of him than just a memoir, we need people like him every day.”

Gomes reflected on his life’s work — and his death — on Charlie Rose’s talk show in 2007.

I even have the tombstone the verse on my stone is to be from 2 Timothy. “Study to show thyself approved unto God a workman who needeth not to be ashamed, rightly dividing the word of truth.” That’s what I try to do, that’s what I want people to thnk of me after I’m gone. When I was young, we all had to memorize vast quantities of scripture and I remember that passage from Timothy I thought, ‘Hey that’s not a bad life’s work.’ And in a way I’ve tried to live into it. So my epitaph is not going to be new to me, it’s the path I have followed in my ministry and my life.

Mike Barnicle talks about the baseball gloves he’s had since 1954. “The Tenth Inning,” is a two-part, four-hour documentary film directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick that premieres this week, September 28 & 29th at 8pm ET on PBS. A new chapter in Burns’s landmark 1994 series, “Baseball,” “The Tenth Inning” tells the tumultuous story of the national pastime from the 1990s to the present day.

Mark Feeney from the Boston Globe says, “Mike Barnicle, who toiled for many years at this newspaper, serves as representative of Red Sox Nation. One of his great strengths on both page and screen has always been what a potent and vivid presence he has.”

Mike Barnicle talks about the Red Sox loss of 2003 to the Yankees and how it impacted his son, Tim. “The Tenth Inning,” is a two-part, four-hour documentary film directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick that premieres this week, September 28 & 29th at 8pm ET on PBS. A new chapter in Burns’s landmark 1994 series, “Baseball,” “The Tenth Inning” tells the tumultuous story of the national pastime from the 1990s to the present day.

David Barron of the Houston Chronicle calls Barnicle’s contribution to the film “perhaps the most valuable addition… (Barnicle) provokes simultaneous laughter and tears on the burden of passing his love of the Red Sox to a second generation….”

“The tale of the Sox bookend years of failure and triumph are given a personal connective thread by former Globe columnist Mike Barnicle, who frames the story through the eyes of his children and his late mother, who, Barnicle recalls, used to sit on a porch in Fitchburg, Mass., her nylons rolled down, listening to the Sox on the radio and keeping score on a sheet of paper.” — Gordon Edes for ESPN.com

Watch here: https://video.pbs.org/video/1596452376/#

“Way Too Early” airs weekdays on MSNBC from 5:30-6:00 AM

Sunday, Jan. 17, 2010

In Massachusetts, Scott Brown Rides a Political Perfect Storm

By MIKE BARNICLE

Scott Brown, wearing a dark suit, blue shirt and red stripe tie in the mild winter air, stood a few yards in front of a statue of Paul Revere and directly across the street from St. Stephen’s Church, where Rose Kennedy’s funeral Mass was celebrated in 1995, telling about 200 gleeful voters that they had a chance to rearrange a political universe. The crowd spilled across the sidewalk onto the narrow street that cuts through the heart of the city’s North End, the local cannoli capital, located in Ward 3 that Barack Obama carried 2 to 1 just 15 months ago.

” ‘Scuse me,” Joanne Prevost said to a man who had two “Scott Brown for Senate” signs tucked under his left arm. “Can I have one of those signs? I’ll put it in my window. My office is right there.”

She turned and pointed across the street to a storefront with the words ‘Anzalone Realty’ stenciled on window. “Everybody will see it.” (See the top 10 political defections.)

Read the rest of the article at: https://www.time.com/time/politics/article/0,8599,1954366,00.html?xid=rss-topstories

Wednesday, December 9, 2009

The Afghan War Through a Marine Mother’s Eyes

By Mike Barnicle

Nearly everything is a sad a sad reminder for Mélida Arredondo: the news on TV, stories in the paper, speeches of Barack Obama and others who talk about a war that seems to have lasted so long and affected so many lives, those lost as well as those left behind.

“Did your son like the Marine Corps?” I ask her.

“Yes,” she replies. “He loved it.”

“And why did he join?”

“Too poor to go to college,” Mélida Arredondo says.

Alexander Arredondo enlisted at 17 and was killed at 20 in Najaf during his second deployment in Iraq. He died on his father’s birthday, Aug. 25, 2004, when Carlos Arredondo turned 44.

“My husband almost killed himself in grief,” his wife says. “The day [the Marines] came to tell us Alex was dead, he poured gasoline all over himself and all over the inside of [their] car and lit it on fire. He survived … physically.”

Read the rest of Mike’s column at Time.com

*NEW* True Compass: The Life of Senator Edward M. Kennedy

THURSDAY, DECEMBER 3, 2009 6:00-7:30 PM

Victoria Reggie Kennedy introduces historians Doris Kearns Goodwin, Michael Beschloss and Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne, who will discuss Senator Kennedy’s memoir, True Compass, his role in history and his legacy with political analyst, Mike Barnicle.

Seating is limited, first come, first served.

10/06/09: Barnicle talks with Jim Braude and Margery Eegan about jury duty and health care reform.

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/10/06/100609-jury-dutyhealthcare-reform.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

09/21/09: Barnicle has a word to say about how technology is affecting the art of letter writing and penmanship being taught in schools today.

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/09/21/92109-writingpenmanship.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

8/31/09: Barnicle talks about the life of Michael Davey, a 34-year-old police officer, war veteran, husband and father cut short after he was struck by a 79-year-old driver last week.

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/08/31/83109-michael-davey.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

Here was Ted Kennedy, 74-year-old son, brother, father, husband, Senator, living history, American legend. He was sitting on a wicker chair on the front porch of the seaside home that held so much of his life within its walls. He was wearing a dark blue blazer and a pale blue shirt. He was tieless and tanned on a spectacular October morning in 2006, and he was smiling too because he could see his boat, the Mya, anchored in Hyannis Port harbor, rocking gently in a warm breeze that held a hint of another summer just passed. Election Day, the last time his fabled name would appear on a ballot, was two weeks away.

“When you’re out on the ocean,” he was asked that day, “do you ever see your brothers?”

“Sure,” Kennedy answered, his voice a few decibels above a whisper. “All the time … all the time. There’s not a day I don’t think of them. This is where we all grew up. There have been some joyous times here. Difficult times too.

“We all learned to swim here. Learned to sail. I still remember my brother Joe, swimming with him here, before he went off to war. My brother Jack, out on the water with him … I remember it all so well. He lived on the water, fought on the water.”

He paused then, staring toward Nantucket Sound. Here he was not the last living brother from a family that had dominated so much of the American political landscape during the second half of the 20th century; he was simply a man who had lived to see dreams die young and yet soldiered on while carrying a cargo of sadness and responsibility. (See pictures from Ted Kennedy’s life and career.)

“The sea … there are eternal aspects to the sea and the ocean,” he said that day. “It anchors you.”

He was home. Who he was — who he really was — is rooted in the rambling, white clapboard house in Hyannis Port to which he could, and would, retreat to recover from all wounds.

“How old were you when your brother Joe died?” Ted was asked that morning.

“Twelve,” he replied. “I was 12 years old.”

Joe Kennedy Jr., the oldest of nine children, was the first to die — at 29 — when the plane he was flying on a World War II mission exploded over England on Aug. 12, 1944.

“Mother was in the kitchen. Dad was upstairs. I was right here, right on this porch, when a priest arrived with an Army officer. I remember it quite clearly,” Kennedy said.

Kennedy remembered it all. The wins, the losses and the fact there were never any tie games in his long life. Nobody was neutral when it came to the man and what he accomplished in the public arena. And few were aware of the private duties he gladly assumed as surrogate father to nieces and nephews who grew up in a fog of myth.

He embraced strangers. Brian Hart met Kennedy at Arlington National Cemetery on a cold, gray November day in 2003. Brian and his wife Alma were burying their 20-year-old son, Army Private First Class John Hart, who had been killed in Iraq. “I turned around at the end of the service, and that was the first time I met Senator Kennedy,” the father of the dead soldier said. “He was right there behind us. I asked him if he could meet with me later to talk about how and why our son died — because he did not have the proper equipment to fight a war. He was in a vehicle that was not armored.

“That month Senator Kennedy pushed the Pentagon to provide more armored humvees for our troops. Later, when I thanked him, he told me it wasn’t necessary, that he wanted to thank me for helping focus attention on the issue and that he knew what my wife and I were feeling because his mother — she was a Gold Star mother too.

“On the first anniversary of John’s death, he and his wife Vicki joined Alma and me at Arlington,” Brian said. “He told Alma that early morning was the best time to come to Arlington. It was quiet and peaceful, and the crowds wouldn’t be there yet. He had flowers for my son’s grave. With all that he has to do, he remembered our boy.”

Ted Kennedy was all about remembering. He remembered birthdays, christenings and anniversaries. He was present at graduations and funerals. He organized picnics, sailing excursions, sing-alongs at the piano and touch-football games on the lawn. He presided over all things family. He was the navigator for those young Kennedys who sometimes seemed unsure of their direction as life pulled them between relying on reputation and reality.

An emotional man, he became deeply devoted to his Catholic faith and his second wife Vicki. He even learned to view the brain cancer that eventually killed him as an odd gift — a gradual fading of a kind that would be easier for his family and friends to come to terms with than the violent and sudden loss of three brothers and a sister, Kathleen. He, at least, was given the gift of time to prepare.

The day after Thanksgiving in 2008, six months after his diagnosis, Kennedy had a party. He and Vicki invited about 100 people to Hyannis Port. Chemotherapy had taken a toll on Ted’s strength, but Barack Obama’s electoral victory had invigorated him. His children, stepchildren and many of his nieces and nephews were there. So were several of his oldest friends, men who had attended grammar school, college or law school with Kennedy. Family and friends: the ultimate safety net. (See video of Kennedy from the 2008 Democratic National Convention.)

Suddenly, Ted Kennedy wanted to sing. And he demanded everyone join him in the parlor, where he sat in a straight-backed chair beside the piano. Most of the tunes were popular when all the ghosts were still alive, still there in the house. Ted sang “Some Enchanted Evening,” and everyone chimed in, the smiles tinged with a touch of sadness.

The sound spilled out past the porch, into a night made lighter by a full moon whose bright glare bounced off the dark waters of Nantucket Sound, beyond the old house where Teddy — and he was always “Teddy” here — mouthed the lyrics to every song, sitting, smiling, happy to be surrounded by family and friends in a place where he could hear and remember it all. And as he sang, his blue eyes sparkled with life, and for the moment it seemed as if one of his deeply felt beliefs — “that we will all meet again, don’t know where, don’t know when” — was nothing other than true.

“I love living here,” Ted Kennedy once said. “And I believe in the Resurrection.”

Barnicle was a columnist at the Boston Globe for 25 years

![]()

Wednesday, August 26th 2009, 6:30 PM

He died on a soft summer night, at home in Hyannis Port, a few days after a storm, the edge of another hurricane, ripped the waters of Nantucket Sound, turning the sky an angry gray.

But now, on the day after he died, the air was clear and there was only the heat of the August sun beating down on the boat, the Mya, that Ted Kennedy so often took to sea, seeking comfort from the past and refuge from the illness now ravaging his system.

Some months before he died, he sat on the porch of the big, white clapboard house he shared with his wife, Vicki, his dogs and his memories – the Hyannis Port house both a home and a museum containing the story of seven decades in the life of one man and a single country.

“When you’re out on the ocean,” I asked, “do you ever see your brothers?”

“Sure, all the time, all the time,” he answered, his voice a whisper. “There’s not a day I don’t think of them. This is where we all grew up.”

And this is where it came to an end, the long dynastic thread woven through world wars, politics, scandal and redemption.

At 77, Edward Moore Kennedy was a man who learned to live with his flaws, his failures and a prematurely ordained future that never was and, after 1969, could never be.

He was the most Irish of four brothers, had the loudest laugh and the biggest voice. He was familiar with pain, emotional and physical. He was sentimental, given to song, poetry and painting. His own hand-painted watercolors adorn the walls of his house.

He suffered greatly from self-inflicted wounds – Chappaquiddick, an affinity for alcohol – as well as the weight of constant expectation that he would, could, might rise and eventually take the White House.

But disruptions caused by the hand of two different gunmen in two different American cities altered him forever, detoured him from the family dream, pushed him to live without a calendar, measuring his days and hours by the whim of a fate he knew he could never truly control.

He became, Kennedy did, a religious man, often attending early Mass with his wife at Our Lady of Victory in Centerville on Cape Cod, knowing that his Catholic faith was rooted in forgiveness.

It is easy to consider how Ted Kennedy might have approached the Lord:

“Bless me Father for I have sinned. It has been – What? – Three weeks? Three years? Three decades? – since my last confession.”

And his penance, if you will, was to serve as a surrogate for three dead brothers and the cargo of lost and wounded children left in the wake of war and assassination; to lose and immerse himself in the freedom of being a legislator rather than be shackled by a myth or become a political vessel for others driven by dreams of dynasty.

He carried his Cross through all the decades, carried it with honor and nobility. He heard every slur, each slander, lost his only quest for the Oval Office and emerged from defeat with a deeper knowledge of who he was and what was meant to be: a life lived in the United States Senate, to negotiate, deal and fight for laws that simply changed how we lived.

Now, the house by the sea, a place once filled with high hopes and even higher ambition, is quiet. And last night’s dusk arrived with a brutal truth: This man who came through the fire of life, scarred but whole, is silent forever, while the fog of memory, seven decades deep, becomes legend on the summer wind.

8/14/09: Barnicle remembers Eunice Kennedy Shriver

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/08/14/81409-eunice-kennedy-shriver.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

8/10/09: Barnicle talks about the past weekend’s contest between the Red Sox and the Yankees and the rancor between the fans.

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/08/11/81009-red-soxyankees.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

8/7/09: Barnicle talks about the Red Sox v. Yankees last night, where the Yankees beat the Sox for the first time this season. Mike also talks about the New Yankee Stadium.

Listen here: https://barnicle.969fmtalk.mobi/2009/08/07/8709-red-soxyankees-and-yankee-stadium.aspx

“Barnicle’s View”, with Mike Barnicle, Imus in the Morning, Monday-Wednesday-Friday, 6:55a & 8:55a.

Mike Barnicle is a veteran print and broadcast journalist recognized for his street-smart, straightforward style honed over nearly four decades in the field. The Massachusetts native has written 4,000-plus columns collectively for The Boston Globe, Boston Herald and the New York Daily News, and continues to champion the struggles and triumphs of the every man by giving voice to the essential stories of today on television, radio, and in print.