NEW YORK DAILY NEWS

Boston getting used to idea of beating New York following so much heartbreak

Friday, December 28th 2007, 4:00 AM

Mike Barnicle, a newspaper columnist in Boston for 30 years, is a long-suffering sports fan and MSNBC commentator.

How did this happen? Was there a specific date, a single event that erased the burden of history and allowed the weight of municipal inferiority to be lifted from the shoulders of every fan in New England who has been witness to decades of humiliation delivered by New York teams?

Think about it.

Saturday, the Patriots play the Giants at exit 16W. They arrive as undefeated favorites, with three Super Bowl championships in four years, the symbol of how a model NFL franchise is run. A dynasty.

The born-again Celtics humiliated the Knicks and Nets each time they met this fall. Of course, the Little Sisters of the Poor could beat the pathetic Knicks, coached by a delusional paranoid and owned by James (Thanks, Dad) Dolan, a soft, spoiled rich guy who inherited wealth, not wisdom.

That brings us to the main event: Red Sox-Yankees. The Yanks have spent billions but they still wear rings tarnished with age while the Olde Towne Team has two championships in the last four years, ’04 and ’07, turning Back Bay into Hardball Heaven. A minidynasty.

It’s a mind warp.

Manhattan was where Boston’s dreams went to die after being fatally wounded in the Bronx. Time turned the Hub into a pitiable afterthought as commerce moved from New England to New York in the 19th century. And sports turned our teams – fans, too – into one-liner fodder for anyone from The Rockaways to New Rochelle.

You used to be able to identify Sox fans in Yankee Stadium. They sat, slump-shouldered, with the same panicked expectation nervous motorists have looking in the rearview mirror at the 16-wheeler behind them on Interstate 95 near New Haven.

The inevitability of collapse was genetic. Disappointment was delivered with an October postmark by fringe figures named Bucky (Effen) Dent, Mookie Wilson and Aaron Boone.

Then, something happened in October 2004 in the “House of Historical Horrors” called Yankee Stadium. The Red Sox came back from three games down to beat the Bronx Bombers, leading the Daily News to hit the streets with one of the greatest front-page headlines ever: “The Choke’s On Us!”

That was IT, the single moment that pushed the gravedigger into retirement. It took the loser label off the forehead of every Boston fan.

Now, in a bizarre way, we have supplanted New York as the place where champions reside and the home team is hated by others. The Patriots are loathed as much as the old Yankees. The Red Sox are fan favorites who attract big crowds in every town, annoying local ownership. The Celtics are dominating the way they used to when they were despised in the old Boston Garden. We’ll skip hockey because the NHL was ruined because of a long strike and ludicrous expansion.

Ironically, we have seen the enemy (the Yankees from DiMaggio to Jeter and Rivera, the once-glamorous Giants of Gifford, Tittle, Huff, Simms and Parcells, the Knicks with Reed, Bradley and DeBusschere, the Jets with Namath) and, incredibly, we have become them.

We have money, swagger, attitude and standing. We’ve consistently won in baseball and football, and we hit the new year with the best basketball record in the NBA. And, given the short national attention span, nobody cares what happened in the 20th century. Life and sports are about the moment.

Oddly, there are thousands of young people from Waterville, Maine, to Waterbury, Conn., who have no institutional memory of a sporting life once filled with apprehension, even fear, who have never endured the depression that accompanied defeat datelined New York City.

But that was then and this is now: Saturday, the victory parade continues and the dominance of area code 212 is diminished, if not dead.

So, how come I’m still up late at night, worrying the Yankees might sign Johan Santana or the Giants might luck out and beat the Patriots by a field goal with less than a minute left in a game where Tom Brady breaks his leg? Maybe it’s because I’m from Boston and haven’t quite gotten used to living with something called success. But I’m getting there.

This time, homicide came to a quiet cul-de-sac in a peaceful suburb, apparently driven by a growing wave of debt built on delusion that collapsed into a despair so deranged that the only escape route Neil Entwistle could allegedly think of was to grab a gun and kill his wife and 9-month-old daughter as both slept in a rented home on Cubs Path in Hopkinton.

The husband’s eyes and appetites, however, in addition to being greater than his budget, appeared to be bigger than his abilities as well.

The district attorney of Middlesex County, Martha Coakley, stood yesterday at a press conference in full command of the facts, unafraid to dispense information, telling the public that the instinct of detectives and prosecutors is that Entwistle could have had suicide on his mind when the nearly incomprehensible occurred in a neighborhood where barking dogs provide the only real noise.

Of course, when that moment of potential self-destruction came – and quickly passed – cowardice overwhelmed the cold cruelty of double murder; Entwistle ran, all the way to the bedroom of the home where he was raised in an English suburb, ran across a whole ocean to the arms of his parents, where he perhaps dreamed that his mother and father could salvage his life from the nightmare he allegedly spawned.

Now, his wife and child dead, Entwistle is handcuffed to a legal system intent on doing to him what he is thought to have done to his whole family – in-laws, parents, everyone: destroy all the years ahead with a conviction for double murder.

But this story is merely at the starting gate because we live in a cable culture where a simple tale of violence is just not enough for many to believe. We think there must be more. We want more. Demand more.

After all, how could a young man do this to the woman he loved and the infant both adored? How could anyone act so irrationally, with such evil, over fear of bill collectors, bankruptcy or the embarrassment of joblessness and admitting failure? What else is there? Another woman? A huge insurance policy?

Unfortunately, the truth is often unsatisfying to those who cannot comprehend the human stories behind nearly every miserable homicide. Murders are almost always darkly interesting, sometimes complex, quite basic and usually sad.

Rachel and Lillian Entwistle are gone. So is the concept of shock and disbelief in American life.

The papers and TV are filled daily with stories that inoculate us all against the trauma of desperate tales. We read and see that four are killed in a basement in Boston, two more shot on a street corner on a Saturday night, children die on sidewalks and schoolyards over a coat, a hat, a look, the wrong word.

Homicide came to Cubs Path. And this morning, Neil Entwistle likely sits in a British jail, fighting extradition for crimes he has been charged with committing. His family is dead. So are their dreams; his too, in a culture where the motive – no money – should not surprise anyone who has been paying attention.

BELFAST — It is a balmy, lemon-yellow evening and I am standing outside a large glass and cement structure called Waterfront Hall, completed last year along the River Lagan in Belfast where people have the capacity to loathe a stranger based solely on beliefs or a baptism. Community input here means a funeral or a fire, yet it occurs to me that in the middle of shootings and bombings they have managed to achieve something that seems out of reach in Boston: They have built a convention center. Earlier, with the town in the grip of unseasonably warm weather, I am strolling White Rock Road in West Belfast, reminded again that a hot sun is truly the full moon for the Irish. Half the men out on stoops are nearly naked, their skin the color of boiled lobster claws.

Here is what you can get in the North: An Armalite-rifle. C-2 explosives. A bazooka. Hand grenades. Flamethrowers. Surface-to-air missiles. A majority voting for peace. And here is what you cannot get: Sunblock.

At the intersection of White Rock and Ballymurphy, Cian Moran is sitting on a milk crate outside his flat. He is wearing a tight blue Speedo bathing suit. He is a heavy man. It is not an attractive sight because his stomach is at war with the elastic waist of the swimsuit and from a distance it appears Moran might be eight months pregnant as he basks alongside his girlfriend, Claire Corrigan, who, incredibly, is not blind.

“Did you bring any of that Viagra with you from America?” Moran wants to know. “That would do the boys a world of good, wouldn’t it luv? That’s the worst moment of a man’s life, failing in bed. I vote yes for Viagra.”

“Worse moment of your life was when the Park View was shut for repairs,” Corrigan tells him, referring to a bar alongside Milltown Cemetery.

That cemetery serves as sort of a huge community center for a people raised on funerals and sad farewells. The caretaker, Sean Armstrong, talks about it as if he were the curator of a macabre Hall of Fame, pointing out where various people’s remains lie, how they died, and whether they were on “active duty” when they fell in the long fight against England.

“Oh, cemeteries are big stuff in Ireland,” Monsignor Denis Faul points out. “Big stuff.”

So are priests. In the absence of a true, old-fashioned political network, priests are a combination of state reps and city councilors who are wired throughout their parishes. Nothing happens without their knowledge. Not a birth. A death. A fight, a plot, a prayer, or a promise. Nothing!

Back in Holy Trinity Church, Mary Kelly sat with bowed head a few days prior to the biggest event in her life. She is 91 and could barely wait to cast a ballot for the future last Friday.

“Not so much for me but for the younger people,” she observed. “People like my son.”

“How old is your son?” she was asked.

“70,” she replied.

In one day, she sat through two Masses, a First Communion, and a gypsy wedding. The church is actually her second home. It is a quiet haven from the horrors that have stalked the old lady’s neighborhood for at least 30 years, filling the streets around her with an awful sadness and a nearly constant violence that leveled off only in the past three years but now, with a tremendous “Yes” vote, could actually recede to the point where children born today could assume a normal childhood tomorrow.

That sound — laughter — remains the hallmark of a resilient people who have survived a horrible history due, in some small measure, to the safety net provided by their own sense of humor. Their city and country have been mangled by murder and bigotry, but the people are still standing, some of them even hopeful, in a place progressive enough to vote for peace as well as build a convention center that can’t get off the ground back in Boston.

BOSTON GLOBE

February 24, 1998

Like most major American cities, Boston is like a layer cake. Some elements are as obvious to the eye as frosting while others remain obscured by simple geography.

Yesterday, for example, a gray Monday, if you walked from the Public Garden to Kenmore Square and back along Newbury Street you could easily think the city was filled by either the young or the wealthy with not many others in between. The eye devours people going to classes along with residents riding a wave of national affluence as well as platoons of out-of-town shoppers — part of a plastic army — arriving in force, ready to toss down their cards as a statement of strength All of it is a distance removed from Egleston, Oak Square, Dudley, Savin Hill, Hyde Park and Roslindale, stops on a transit map to most. Yet even here, fresh paint, economic ventures, and a new broom on old stone sidewalks have delivered the gift of optimism plus an increased sense of security to neighborhoods that not long ago were dark with gloom and fear.

There is the tourist town. And there is the traveled town.

There is the town that swells by day with workers who fill office buildings, insurance firms, and brokerage houses and then depart at dusk. And there is the town where people actually live, pay taxes, put their kids in school, and look to trash collection, public safety, a clean park, a functioning traffic signal, or a visible STOP sign as daily barometers of whether government is indifferent or involved.

Away from the bright lights and the allure of bistros stuffed with symbols of expense account confidence, though, it is hard to escape the conclusion that a majority seems satisfied. As always, the public is smarter and more aware than it is made out to be by a media infatuated with negativism, chronic bad news, and suffering from the infection of cynicism.

Ordinary people don’t require polls to get through their day. They don’t need to put a “spin” on every move. They know that life is not a sound bite. That image is not reality and perception isn’t nearly as important as a paycheck.

One lingering image of Boston — one hashed and rehashed each time the city is mentioned — is that it is extremely liberal, almost abnormally left. But, like the frosting on the cake, philosophy differs once your feet take you away from the center.

There isn’t another state in the union where the biggest city happens to be the center of commerce, media, industry, and education in addition to its political capital. New York has Albany. Pennsylvania has Harrisburg. California has Sacramento. In Illinois, it’s Springfield.

And, as is often the case, people are not necessarily as they are portrayed by polling data or even election results. They are, at their root, sensible rather than confrontational; not much different than others from Cheyenne, Wyoming, to Austin, Texas, to Battle Creek, Michigan.

Sometimes, the view through a prism of pre-ordained judgment and instant observation isn’t simply flawed; it’s flat out inaccurate: Boston, the Kennedys, Harvard, McGovern in ’72, hopelessly, romantically and nostalgically liberal.

You might want to keep this in mind while watching a tremendous two-part documentary that began last evening on PBS devoted to the life of Ronald Reagan. Scorned in places like Back Bay and Beacon Hill, Reagan will find more favor in history than the fellow who occupies the White House this morning.

Maybe because, like a lot of average Americans, Reagan — admire him or not — had beliefs. He had an internal compass, a bit of character, and a life apart from politics.

Oddly enough, he seems not to have been consumed with ambition. Not ever. Always, he was comfortable with himself, happy with whatever part he played. And — a huge asset — he had the ability to make others comfortable, to soothe rather than supplicate himself or seek sympathy.

Sure, he presided over the Iran-Contra scandal, the arms-for-hostages debacle. But then, he went to the country and apologized for not being fully engaged and admitted a mistake. How different!

He did something not many politicians, other than Roosevelt, managed to do: Change how people think about government — that it actually might be too large, might truly play too powerful a role in the everyday life of ordinary Americans.

Like a city, Reagan’s life and presidency had layers that were not always obvious or appreciated. Turns out, the man was more than just frosting on a cake.

Like most major American cities, Boston is like a layer cake. Some elements are as obvious to the eye as frosting while others remain obscured by simple geography.

Yesterday, for example, a gray Monday, if you walked from the Public Garden to Kenmore Square and back along Newbury Street you could easily think the city was filled by either the young or the wealthy with not many others in between. The eye devours people going to classes along with residents riding a wave of national affluence as well as platoons of out-of-town shoppers — part of a plastic army — arriving in force, ready to toss down their cards as a statement of strength All of it is a distance removed from Egleston, Oak Square, Dudley, Savin Hill, Hyde Park and Roslindale, stops on a transit map to most. Yet even here, fresh paint, economic ventures, and a new broom on old stone sidewalks have delivered the gift of optimism plus an increased sense of security to neighborhoods that not long ago were dark with gloom and fear.

There is the tourist town. And there is the traveled town.

There is the town that swells by day with workers who fill office buildings, insurance firms, and brokerage houses and then depart at dusk. And there is the town where people actually live, pay taxes, put their kids in school, and look to trash collection, public safety, a clean park, a functioning traffic signal, or a visible STOP sign as daily barometers of whether government is indifferent or involved.

Away from the bright lights and the allure of bistros stuffed with symbols of expense account confidence, though, it is hard to escape the conclusion that a majority seems satisfied. As always, the public is smarter and more aware than it is made out to be by a media infatuated with negativism, chronic bad news, and suffering from the infection of cynicism.

Ordinary people don’t require polls to get through their day. They don’t need to put a “spin” on every move. They know that life is not a sound bite. That image is not reality and perception isn’t nearly as important as a paycheck.

One lingering image of Boston — one hashed and rehashed each time the city is mentioned — is that it is extremely liberal, almost abnormally left. But, like the frosting on the cake, philosophy differs once your feet take you away from the center.

There isn’t another state in the union where the biggest city happens to be the center of commerce, media, industry, and education in addition to its political capital. New York has Albany. Pennsylvania has Harrisburg. California has Sacramento. In Illinois, it’s Springfield.

And, as is often the case, people are not necessarily as they are portrayed by polling data or even election results. They are, at their root, sensible rather than confrontational; not much different than others from Cheyenne, Wyoming, to Austin, Texas, to Battle Creek, Michigan.

Sometimes, the view through a prism of pre-ordained judgment and instant observation isn’t simply flawed; it’s flat out inaccurate: Boston, the Kennedys, Harvard, McGovern in ‘72, hopelessly, romantically and nostalgically liberal.

You might want to keep this in mind while watching a tremendous two-part documentary that began last evening on PBS devoted to the life of Ronald Reagan. Scorned in places like Back Bay and Beacon Hill, Reagan will find more favor in history than the fellow who occupies the White House this morning.

Maybe because, like a lot of average Americans, Reagan — admire him or not — had beliefs. He had an internal compass, a bit of character, and a life apart from politics.

Oddly enough, he seems not to have been consumed with ambition. Not ever. Always, he was comfortable with himself, happy with whatever part he played. And — a huge asset — he had the ability to make others comfortable, to soothe rather than supplicate himself or seek sympathy.

Sure, he presided over the Iran-Contra scandal, the arms-for-hostages debacle. But then, he went to the country and apologized for not being fully engaged and admitted a mistake. How different!

He did something not many politicians, other than Roosevelt, managed to do: Change how people think about government — that it actually might be too large, might truly play too powerful a role in the everyday life of ordinary Americans.

Like a city, Reagan’s life and presidency had layers that were not always obvious or appreciated. Turns out, the man was more than just frosting on a cake.

It is Friday night. I am in a hall filled with a thousand other admirers who have driven through snow and sleet to salute a wonderful woman, Eileen Foley, who was born in February 1918 and was mayor of Portsmouth, N.H., longer than anybody else. And, because the room was packed with political people, I kept returning to another evening nearly six years ago, when New Hampshire helped pull Bill Clinton’s candidacy in off the ledge he had walked onto, hand-in-hand with Gennifer Flowers.

Then, as now, the charge was reckless infidelity. Then, as now, Clinton, a skilled semantic contortionist, confronted it with the language of lawyerly loopholes in a tortured effort to put forth some preposterous claim that he was answering the questions and telling the truth “It’s like he’s accused of robbing a bank,” Eileen Foley’s son Jay was saying. “And he gets up there and says, `Absolutely not. Those allegations are untrue. I did not rob a bank.’ Later on, when he gets caught, he tells us, `You don’t understand. I didn’t lie. I never robbed a bank. It was a savings and loan.’ “

Initially, some felt a weary sadness upon hearing that the president may have had sex with a 21-year-old intern. Now, frustrated and angered by his inability to issue a flat-out denial devoid of linguistic tricks, the crowd lives with the uneasy knowledge that they have a terribly flawed man in the White House whom they trust with the economy but not with their own daughters.

But you can hear the inevitable assault coming from Washington, the attack on the former intern. Within a week — either by innuendo or off-the-record “briefings” — she will be described as an emotionally insecure girl, a flirt, a delusional coed with a crush, someone who, clearly, should have been carted off to an asylum, rather than allowed to work in the White House.

This is the predictable pattern with this president, a man of tremendous gifts and abilities: His public life too often involves a forced retreat from the truth. Isolated from reality, surrounded by power, obviously under the impression that he is both invincible and invisible, Clinton always turns himself into the victim. His battlefields are littered with the remains and shattered reputations of former friends and old lovers.

He succeeds because he is smart enough to know he can make today’s culture complicit in his conspiracy. Apart from his wife, the women who swirl around him are of a type: They are young or vulnerable or ill-equipped to deal with the klieg lights of propaganda and publicity. They are interns, state workers, widows, or fortune seekers.

Class dominates our society. The rich, the powerful, the connected and the pretty know how to get the benefit of the doubt. Brass it out by pointing a finger at an accuser who has big hair, nervous eyes, a temp’s credentials or only one story to tell. Surely, you can’t believe them!

With Clinton, you’d need a platoon of psychiatrists to even approach the problem. Raised without a father, he has probably never been told to sit down, keep quiet, admit the truth and accept the consequences. For 50 years, he has — all by himself — been the man of the house; charming, smart, handsome, glibly articulate and ferociously ambitious, his very own role model.

When you think of that late winter six years ago, the arrogance is breathtaking: The draft, the women, the marijuana, all of it explained away with a wink, a nod and an eye toward a trapdoor knowingly built with evasive language.

Six years later, in a room where citizens assembled Friday night to salute a magnificent woman, it was clear that the country is fine and will survive any assault that has its origins in a sad episode of a man’s own self-destruction, assembled with the assistance of a pathetic inability to control himself.

Eileen Foley’s family spoke of their mother with humor and affection. And then, Senator Bob Kerrey of Nebraska stood to tell the crowd he was not in Portsmouth because of February 2000, but because of February 1918, the month and year when Eileen Foley was born, “the year of the Great War when men from the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard stood in the frozen snow for the idea of freedom,” Kerrey said. “She is a woman of honor and courage whose life tells us the wonderful story of America.”

We might end up limping through three years of a government headed by a kind of Joey Buttafuoco with Ivy League polish. But on a night when a terrific 80-year-old woman heard the applause of heartfelt gratitude, two things were obvious: It’s Clinton’s legacy, but it’s our country.

A regal funeral closer to home

Mike Barnicle, Globe Staff

7 September 1997

The Boston Globe

Long before yesterday’s funeral began, a huge crowd assembled inside the magnificent church where everyone gathered in a crush of sadness over the death of a sparkling young mother who touched many lives before she was killed in a horrific car crash a week ago, across the ocean, far from home. Mourners came in such numbers that they spilled out the doors of St. Theresa’s Church, onto the sidewalk, and across Centre Street in West Roxbury as police on motorcycles and horseback led two flower-cars and three hearses to the front of a beautiful church filled now with tears and memory.

Yesterday, the wonderful world of Mary Beatty Devane was on display to bury her along with two of her daughters — Elaine, 9, and Christine, 8 — who also lost their lives on a wet road east of Galway City as they headed to Shannon Airport at the conclusion of their vacation. Her husband, Martin, their daughter Brenda, 5, and their son Michael, 2, survived the accident and, after the hearses halted at the curb, Martin Devane emerged from a car, his entire being bent, injured, and slowed by the enormous burden of his tragic loss.

The Devanes represent one of the many anonymous daily miracles of this city’s life. They lived around the corner from where Mary grew up in a house headed by her father, Joe Beatty, the president of Local 223, Laborers Union, who arrived in Boston decades back from the same Irish village, Rusheenamanagh, where Mary’s husband, Martin, was born.

He is a construction worker. She was a nurse. They were married 11 years and their life together cast a contagious glow across their church and their community.

Now, on a splendid summer Saturday, when the world paused for a princess, up the street they came to cry for Mary Theresa Beatty and her children. There were nuns and priests, cops and carpenters, plumbers, teachers, firefighters, and nurses side-by-side with farmers who flew in from rocky fields an ocean away. A global village of friends inside a single city church.

Bagpipes played while 16 pallbearers gently removed three caskets from the steel womb of the hearses. The weeping crowd formed a long corridor of hushed grief as the caskets were carried up the steps and down the aisle toward 17 priests who waited to apply the balm of prayer to the wounded mourners.

Mary Devane worked weekend nights in the emergency room at Faulkner Hospital. When she was not there, she was either caring for her own family or tending to the dying as a hospice nurse.

During her 31 years on earth, she was many things: wife, mother, daughter, sister, nurse, neighbor, healer, helper, compassionate companion to the suffering, angel of mercy for the ill, smiling friend to an entire community that stood yesterday in collective silence in a church cluttered with broken hearts.

As the pallbearers transported their precious cargo, 22 boys and girls from St. Theresa’s Children’s Choir rose alongside the parish choir to sing “Lord of All Hopefulness.” No cameras or celebrities were present — simply the pastor, the Rev. William Helmick, along with all the others there to celebrate a life lived well and taken too soon.

The 70-year-old church swayed with psalm, hymn, and gospel; with the “Ave Maria”; with voices of youngsters struggling to sing for their classmates Christine and Elaine, who had been scheduled to start third and fourth grade at St. Theresa’s grammar school, 50 yards away.

Larry Reynolds stood in the choir loft, high above the congregation. With strong, rough carpenter’s hands, he gently held a fiddle and began to play “The Culan,” a 400-year-old Gaelic song. As communion commenced below, each of his notes echoed a tear throughout the immense stone building.

Reynolds himself is from the County Galway village of Ahascragh. He has known both families, the Beattys and the Devanes, for 30 years, and after he finished, Mary Twohig, a nursing school classmate of Mary Devane, walked slowly to the podium to recite “A Nurse‘s Prayer” and share an elegant eulogy with all those devastated by these three deaths.

Then, the Mass ended. Incense caressed the air as the pallbearers retreated through the church and out to those hearses idling at the curb before the big crowd drove off in thick traffic for the sad trip to St. Joseph’s Cemetery, where Mary Beatty Devane and her two precious little girls were set to final rest, three members of a truly royal family.

MIKE BARNICLE

Hong’s incredible journey began on the day 11 years ago when he sat confined to the dust of his fishing village near Can Tho in Vietnam and suddenly heard someone mention America. Of course, Hong did not actually hear what the person was saying because he has been deaf since birth. But he sure did understand the primitive sign language being employed and his heart soared at the thought of all the possibilities that might be available to him in a land of endless dreams.

“They said something about America,” he recalled the other day, “and that was enough for me. I left on a small boat from Nha Trang, and after a long time on the ocean we got to the Philippines “I was in a camp four years. All the time, trying to get here. After four years, my wish came true.”

His name is Hong Ngoc Nguyen. He is 37 years old and he stands today as the ultimate rebuttal to anyone attempting to trash this country through handwringing editorials or pathetic talk-show whining, so much of it aimed at having people think we are all merely part of some cowboy culture filled with constant violence and obnoxious vulgarity rather than the brightest star in the world galaxy.

Hong spoke through an interpreter, Hannah Yaffe, outside a first-floor classroom in the DEAF Inc. offices on Brighton Avenue, a block from Union Square in Allston. He was among several hearing-impaired immigrants present the other afternoon who come to DEAF daily to learn both signing and English so they can live a better life in a land of promise.

Cathy Mylotte was assisting Ms. Yaffe with interpretation because she knows Hong quite well and absolutely knows what he has had to endure. She too is deaf. She arrived in the United States from Galway, Ireland, in 1970 and has dedicated nearly every day since to helping others like her succeed at things so basic they are taken for granted by the rest of us: grocery shopping, driving a car, catching a bus.

“There was no education for me in Vietnam,” Hong said in sign language. “I came here because I love the word `America’ and I knew there was school here. As soon as I come 11 years ago, I work hard to be good American.”

“Where do you work?” he was asked.

“First job,” he reported with excitement, “was in grocery store. I stack shelves. Good job.

“That was in the day. At night, I help sand floors. That was good job, too. Weekends, I work with my brother at fruit store.

“Now, I work for medical equipment company in Braintree, the CPS Company. Wonderful job.”

His hands seemed to somehow share the smile that creased his face as he used them, flicking fingers back and forth with tremendous speed, to tell Hannah Yaffe and Cathy Mylotte about his marvelous new life. He told them he could remember feeling vibrations from air raid sirens and artillery rounds as a child, growing up with his parents, three brothers, and three sisters in the Mekong Delta where the entire family lived meagerly off the land and the water.

He told them about being helped by Peace Corps workers and American Maryknolls in the Philippines. About his older brother, Bau Nguyen, who is 42 and accompanied Hong through the camps and across the sea to Boston and is employed today as a case worker for the state welfare department. Then, he happily informed everyone in the room that he finally returned to Vietnam in February to marry a woman from his village and hopes that she will be able to join him here soon.

“We had a huge banquet after the wedding,” Hong declared. “It was very expensive. I paid.”

“What makes you proud?” Hong was asked.

Without hesitation, Hong told Hannah Yaffe: “On July 3, I became a citizen. I stood in a big hall and was made an American. I studied very hard for the honor. I have pictures that were taken that show me being a citizen.”

Now, Cathy Mylotte placed her hand on Hong’s shoulder, and both people beamed with a fierce pride born out of incredibly hard work that the hearing world cannot begin to comprehend. We are surrounded by so many who constantly complain and understand so little about our history and heritage that these two deaf citizens symbolize with their positive, refreshing testimony what this place — America — is truly all about.

“Ask him what he wants to do,” Cathy Mylotte was asked.

“I want to do everything,” he laughed.

BOSTON GLOBE

July 31, 1997

As soon as everyone had gathered in St. Ignatius Church at Chestnut Hill yesterday for the funeral Mass, a full company of Jesuits marched silently down the center aisle of the handsome stone edifice to bury a brother, Rev. Ray Callahan, SJ, who fell dead at his desk last week at 59. Until his death, Father Callahan had been president of Nativity Prep in Roxbury, a miracle of the city where children are given the gift of a future.

It was 10 a.m. when the Jesuits took their seats directly across the aisle from Marie Callahan, the deceased priest’s mother, who sat sadly with her daughters. She wore a black dress and held a single white rose Outside the church, the sun stood sentry in a cloudless sky and a wonderful breeze danced across the day. Inside, people stood shoulder to shoulder singing “Here I am, Lord” as five Jesuits began the beautiful ceremony.

There were no TV cameras or any reporters clamoring for participants to discuss the quiet, noble life of Ray Callahan, who never sought a headline. He was born in Framingham, son of a newspaperman, and he went to Fairfield University until God tapped him on the chest with such ferocity that he chose the Marine Corps of Catholicism — the Jesuits — as a life.

He taught at Boston College as well as at BC High, but for the past several years he had run Nativity Prep. It is a small, private school — 15 students in 4 grades, 5 through 8 — where boys from places like Mattapan, Roxbury, and Dorchester get just about the finest free education around.

“Anybody can learn math,” Ray Callahan used to say, “but our job is to help these boys gain pride and dignity, too. They are wonderful, strong children.”

All this week, the town has witnessed a flood of publicity concerning the future of William Weld. And as the funeral began, a new governor, Paul Cellucci, was in the State House discussing tax cuts and judgeships. All of it is considered news because these people and their policies affect so many.

However, Ray Callahan was a single man who touched a thousand lives. He was a Jesuit priest who had a hand on someone’s shoulder every single day, pushing or prodding them toward heights once thought to be unattainable.

As Rev. William Russell, SJ, delivered the homily, one of the many Nativity Prep students at Mass bowed his head in grief. His name was Adrian Rosello. He is a 13-year-old from Mattapan who will be in eighth grade this September.

“I never expected him to die,” Rosello said quietly. “I loved him. He always made me laugh and told me I could do better. He believed in me. How could he die in the summer?”

Now, at Communion, Mike Burgo came from the sacristy holding a guitar. He began to sing the infectious hymn “Be Not Afraid” and soon the huge congregation joined Burgo, the sound of their grateful voices filling the church and spilling out toward the trolley tracks and the campus of Boston College.

“You shall cross the barren desert, but you shall not die of thirst. You shall wander far in safety, though you do not know the way. You shall speak your words in foreign lands, and all will understand. You shall see the face of God and live.

“Be not afraid. I go before you always.”

Both song and service are part of the constant comfort of Catholicism, a religion that blankets the start and conclusion of life with splendid ritual. But Ray Callahan represented the finest aspects of his faith every single day. He led by example, a humble man dedicated to God and to education.

And yesterday his legacy filled St. Ignatius: Former students; young people like Amy Shields, who went straight from Duke to teaching at Nativity Prep because providing a child with the excitement of ideas is far more rewarding than making money; hundreds of friends; and his fellow priests.

Then the Mass ended and the Jesuits filed out to the front of the church where they stood in a circle on the sidewalk, resplendent in white cassocks, as six Nativity Prep boys carried a black casket down gray cement steps. They were followed by Marie Callahan, who walked slowly out of the church into the bright sun of a day, comforted by the knowledge that while others elsewhere celebrated temporal rewards of prosperity or politics, the crowd around her had gathered to celebrate the rich and marvelous life of Raymond J. Callahan, SJ.

“Thank you for your son,” Rev. William Leahy, the president of Boston College, said to Marie Callahan.

“Thank God for my son,” his mother replied.

BOSTON GLOBE

June 15, 1997

So here she came the other day, walking through the haze of a humid afternoon, walking proudly up Adams Street in Dorchester past a line of red brick rowhouses where children sat on stoops seeking relief from the heat, walking right into a future filled now with potential due to her own diligence.

Her name is Phong Tran and she is 17 and she has only been in the United States since 1991 — time enough, though, to finish at the top of her Cathedral High class and win a four-year scholarship to UMass-Amherst, where she will be one more Vietnamese student representing the constant American spirit of renewal “It is like a dream,” Phong Tran pointed out. “I am so grateful. I am so happy.”

“With no scholarship, where would you go?” she was asked.

“To work,” Phong Tran replied.

“What do you want to be?”

“A doctor,” she said right away. “So I can help others. So I can repay people for my good fortune.”

The young woman earned her fortune all by herself. And she is only one of 83 premier students from across the state who have been granted a gift worth $8,000 a year simply because they were smart enough to be smart.

The University Scholars program is a new benefit provided by the state’s university system. This year, four-year scholarships were offered to those seniors who finished first or second in their classes at each of Massachusetts’ 400 public and private high schools. Tomorrow, many of the 83 who accepted the scholarships will be honored at a State House reception.

For decades, the UMass system has been smeared by elitists and relegated to second-class status in a commonwealth that boasts a long line of more famous and more expensive private institutions. But, whether at Harvard or UMass-Lowell, nobody is ever given an education, only the opportunity to get one — grab one, really — and that chance is not lost on those students and families going now for free.

“My daughter is very ambitious,” the Rev. Earl McDowell was saying Friday. “We teach all our children to be ambitious, to have goals and go after them. She did, too.”

Rev. McDowell was sitting in the second-floor parlor of his Roxbury apartment along with his wife, Patricia. The two parents were crazy with pride over their daughter Valerie, who topped the ticket at Madison Park High and will be going to UMass-Boston in September. Both young women — Phong Tran from Vietnam and Valerie McDowell from Guild Street — take a splendiferous spirit off to their amazing new world.

“She just graduated last night,” Patricia McDowell explained. “She was the valedictorian. The ceremony was at Matthews Arena, and she walked in with all the dignitaries.”

“I had tears in my eyes,” her husband added.

“She’s the first in our family to ever go to a four-year college,” the mother said.

“She worked hard for it,” Rev. McDowell said. “She had three part-time jobs all year, too. This scholarship is a true blessing because, as you can see, I took a vow of poverty.”

“He took it seriously, too,” his wife laughed.

“Valerie has always been a straight-A student,” the proud father continued. “At the Nathan Hale. At the Wheatley and all through Madison Park. We are firm believers in public education, but it’s a matter of determination and parental involvement whether your children do well.

“It’s not up to society, to the city, or to the police to provide children with goals and ambitions. It’s up to us as her mother and father,” Rev. McDowell stated. “If a black youth is nothing, it means they chose to be nothing.”

“Basically, we have tried to be our daughter’s best friends as well as her parents,” Patricia McDowell added. “It’s good that way. We were able to guide her away from trouble, and if our children meet someone not up their standards, we let them know. And they just say `goodbye.’ “

Now, the valedictorian from the night before was ready to go to work on the morning after her triumph. Valerie McDowell, symbol of any future we might have, is a marvelous young woman who only dreamed of a university education prior to the gift of a four-year scholarship.

But sometimes dreams come true. And sometimes hard work, discipline, and dedication are rewarded, and when that happens, the grateful — like Valerie McDowell and Phong Tran — head to college, two magnificent investments in a state of mind.

BOSTON GLOBE

June 8, 1997

Orla Benson, murdered on Sept. 23, 1995, in an Allston playground, was young and alive again Friday as her biographer discussed her wonderful life in glowing terms while a Suffolk Superior Court jury was being selected to try the man charged with her killing. Benson had come from Ireland that summer to work when she was raped and stabbed to death by a degenerate who left her dead in the dark on the steps of Ringer Park.

“Orla was a nice girl,” Thomas O’Leary was saying. “She was young and pretty and totally innocent. And she had just spent the happiest night of her life in Boston when this happened. She would have graduated from college that fall “She was out with about 30 friends. They had been to South Boston, to Cambridge, to Brighton. They rented a trolley for a party to celebrate a girl’s wedding, and they were going home to Ireland in a few days. She was 50 yards from her apartment.”

O’Leary today is Orla Benson’s voice, her best friend in court. He is a sergeant of police with the Homicide Unit, and his duty since early in the day that Sept. 23 has been to bring her killer to court and help deliver some measure of justice to her horribly wounded family.

It is always an event of tremendous significance, the murder of a human being. And whether it is multiple counts, as in Oklahoma City, or a single victim, the word “closure” becomes something for glib psychiatrists or talk-show callers because the pain of survivors is of such depth and duration that it simply becomes part of their own existence.

“Plenty of sleepless nights over this one,” O’Leary said. “I can see her sometimes. I know her.”

In the courtroom, Benson’s father, Tom, an engineer from Killarney, sits daily not 10 feet behind Tony Rosario, a convicted rapist who is accused of forever silencing the sounds of Tom Benson’s only daughter’s life. The elder Benson is of slight build and has a soft spring rain of a smile and gentle blue eyes permanently dulled by this inexcusable death.

Rosario is 29 now. He was born in New York and brought up in Boston, where he was a menace. All last week, he wore a blue sweatshirt, black pants, black sneakers, leg irons and no hint of expression on a face unfamiliar with remorse as he listened to pretrial arguments of the prosecutor, James Larkin, and the objections of his own gifted appointed counsel, Roger Witkin, in the third-floor room where a panel of citizens will address the brutality of Orla Benson’s murder.

Rosario is a living advertisement for the flaws of a system where a single bureaucratic error can result in a monstrous evil being committed. In 1991, he was convicted of raping and beating a woman at the Forest Hills T station. He got 10 years but was out two years later.

Free on probation, he was arrested on April 24, 1994, for raping a 14-year-old runaway at knifepoint after she fled, naked, from his car. But the runaway kept right on running and would not testify, so Rosario went unconvicted.

He was indicted for unarmed robbery in Cambridge, but somehow never had his probation revoked. Then on July 31, 1995, seven weeks before Orla Benson died, Rosario was grabbed for the rape of a 15-year-old special needs student in Brighton. She had been working for Rosario, who had, quite amazingly, been hired by the city’s Parks and Recreation Department to boss teenagers retained for a summer of cleaning playgrounds.

“He told her unless she had sex with him, she wouldn’t get paid,” a lawyer familiar with the case of the special needs student said, adding that Rosario took her to his apartment on Glenville Avenue in Allston “and told her: No sex, no check. But, because she was retarded, he beat it.”

“He never should have been out,” Tom O’Leary said. “The system took a hit for him being on the payroll. Probation took a hit, too. But Orla took the biggest hit of all.”

Thursday, Rosario had an opportunity for minimal decency when he accepted, then reneged, on an agreement that had him pleading guilty to first-degree murder. But lunch with jailhouse lawyers, along with success in beating the system and making a sad joke of probation, caused him to change his mind.

So Tom Benson and his family will be forced to endure a trial where his daughter will die again; a trial where judge and jury will surely see in the testimony offered that this world needs people like Orla Benson as much as it needs a sunrise, because her biographer remains on the case, insistent on delivering his message.

“I know her,” said Sergeant Thomas O’Leary. “She was a wonderful girl.”

BOSTON GLOBE

March 27, 1997

One of the babies who represents the future for these young girls pushing a carriage instead of carrying books was being wheeled down Mercer Street in South Boston yesterday by her mother, who is not quite 17. The mother was white and the infant a wonderful shade of mocha, which sure made her beautiful but appears not to have inspired much glee in the household where she is being raised.

“My boyfriend’s black,” the girl pointed out. “And my mother hates him. She don’t hate the baby, but she hates what happened, you know In projects like D Street and Old Colony, there seems to be a significant increase in the number of interracial infants born to white teenagers. Many of these girls drop out of school prior to giving birth and try to raise their own baby in the same apartment where they had been attempting to grow up when a pregnancy interrupted the process.

“There are quite a few white girls having babies with black and Hispanic guys here,” one of the police who specializes in South Boston project life was saying yesterday. “It’s a good news-bad news story: The good news is that race is not the factor in these kids’ lives that it was — and is — for a lot of their parents. Kids don’t have the same hangups as adults. Kids don’t go around talking about what busing did to their town. That was 20 years ago. They weren’t even born.

“The bad news is it means the end of the line for the girl: dropping out of school, no job, raising a kid where her mother, father, too, if he’s around, can’t stand looking at the baby because the baby’s not white.”

Yesterday, the girl pushing the stroller had a plan: She intended to walk to Rotary Variety for milk and then visit a friend on Silver Street. Her plan was built around the premise that she should try to remove herself and her child from the apartment for at least five hours. Kind of like a job.

For some, the increase in interracial children represents another assault on “The Town.” South Boston has been staggered by suicide and drugs. One — kids killing themselves — is a shock. The other — cocaine and heroin — is an old habit, narcotics having been easily available there for a long time.

At a community gathering the other evening, a suggestion was made that more police were needed to fight drugs and restore the mythic sense of “neighborhood.” But the statement was made in a section of the city no longer immune to social conditions that cause deterioration: alcoholism, addiction, AIDS, teenage pregnancy, illiteracy, poverty, unemployment, fractured families and rampant rates of divorce or abandonment.

Yet police alone cannot do the job. Nor can schoolteachers, priests or social workers. The type of work necessary can only be accomplished by a parent, and in the projects of South Boston, like projects everywhere, too many parents are poor or ill-equipped for the task or juveniles themselves or AWOL from responsibility. To ignore this is ludicrous.

“It’s a bizarre form of equality,” the police officer was saying. “And it’s filled with irony. Many of the white kids in D Street or Old Colony are in the same position as a lot of black kids in Roxbury and Dorchester: They have no shot and they know it by the time they’re 15.

“They’re poor. For a lot of them, there isn’t a parent around. They don’t go to school, so they do whatever is free and feels good.

“Now what can 100 more cops do about that? We can patrol. We can investigate. We can arrest. We can get a warrant and go in an apartment but we cannot go inside someone’s head and force them to change their behavior.

“And it’s not just cocaine taking a toll on South Boston. Look around and you will see more bars, taverns and package stores in this community, per capita, than probably anyplace else in the city. You fall down drunk and people think it’s funny, actually kind of normal. You overdose and it’s a tragedy, but they are both addictions and there are plenty of addicts to go around in this town.”

Still, some in South Boston seem amazed at the ages of the desperate or those already dead by their own hand. And the enormity of the problem is such that others either refuse to recognize it or mistakenly feel that it is restricted to project life where a baby can face a bleak future because its very existence serves as a reminder of failure rather than a source of joy.

Phew! Good thing Ted Kennedy didn’t decide to throw his weight around the other night because then he would’ve absolutely crushed Mitt ”I’m Talking As Fast As My Nervous Little Motor Mouth Will Move” Romney. That collision would’ve looked as if an 18-wheeler loaded with dumpsters had plowed into one of those teeney-weeney old Nash Metropolitans. As it was, he slapped him silly. Kennedy slam-dunked the bragging Boy Scout from Belmont so often that The Mittster is down to a couple of options prior to tonight’s debate: Either jump-ugly at the senior Senator over, ahh, the character issue, or cut his losses and save a pile of dough for another run at another time because this one is halfway through that last revolution in the toilet. How quickly things change.

Seems like it was only days ago that all the haters and a lot of the professional thumb-sucking pundits were writing Kennedy off. He was too old, too fat, too dumb, too tongue-tied, too entrenched, too isolated, too removed, too arrogant, too elitist, too tied in to the status quo to win anything.

Listening to them, you half-expected Kennedy to walk out on stage at Faneuil Hall, peer at the crowd and holler: “This Bud’s on me.” Or maybe demand that the moderator hit him with a pinch and a couple of cubes.

A funny thing happened, though: Romney arrived with a knot the size of an official NBA basketball right where he fastens the top button of his hand-made shirt.

He is a nice fellow, a pleasant man. He is handsome, polite, glib, smiling, smart, rich, goes through life without a single hair out of place, waves at poor people one day a week and thinks a walk on the wild side means drinking a cherry Coke.

However, he has no idea how much his health plan will cost taxpayers and sure isn’t responsible for anything that occurs at some plant he helped purchase. Why should he know that? He’s only the owner.

Kennedy, on the other hand, has managed to become a somewhat sympathetic figure. Before Tuesday, many observers were convinced the night would be a disaster for the senator, whose use of language manages to make the late Frank Fontaine or Professor Irwin Corey sound like Abba Eban or Adlai Stevenson.

They were ceding the thing to Romney on appearances alone. His waist size equals the number of years Kennedy has served in the US Senate. He has never suffered so much as a pimple, never mind any personal pain and, according to his own answers, he is pretty much without a flaw.

Meanwhile, the negative build-up and dread surrounding Kennedy’s difficulty in finding verbs to go with nouns and objects, plus the added burden of putting action words in their proper place throughout a spoken English sentence, so lowered the expectations that the mere fact he didn’t fall off the stage into the audience was a victory.

And you know what? It was great. It was a victory for old guys, for out-of- shape guys, for guys who are counted out before the bell, for guys folks figured would never hit in the clutch.

Ted Kennedy won because he is stubborn in his beliefs. You may not like his views, and you may not like him, but at least he’s not running around suddenly seizing upon the electric chair or welfare cheats as the trendy ticket he needs for a return trip to the Senate.

He’s the government guy, the go-to-guy when you’re looking to have the feds pick up the cost of 16 additional weeks of unemployment compensation, get you the extra bounce in child care and Head Start appropriations, get money back from Washington to help lower astronomical MWRA water bills. Maybe you think stuff like that is a bunch of liberal horseshirt.

He doesn’t. He makes no apologies for who he is and what he believes. He has a philosophy that isn’t pushed around by pollsters. Perhaps some of it is dated, but the man is consistent.

He’s 62 and looks it. He has lived through a cargo of grief, and inflicted a lot of it upon himself. He has had some terrible difficulties and they have not been hidden. His life has been a long, public sorrowful mystery of the rosary.

Ted Kennedy is many things, but none of them is a secret. He might be in the back of his van this morning eating quarter-pounders and fries between every stop and it wouldn’t go unnoticed. (I never thought ears put on weight until I saw his on TV Tuesday.) Why, if you put Bill Parcells and Kennedy on either end of the Boston Public Library, they could serve as human bookends for a whole building.

For a long time, people were down on him, figuring he was afraid to take his turn at bat against a formidable young foe. Well, the other night Ted Kennedy gave the young guy a good old-fashioned arse-whipping because he still wants to win.

“I was driving the chief,” Walter Cobe was saying. “We got there just as Engine 48 pulled up. It was maybe three or four minutes after the alarm was sounded. I jumped out of the car and one of the people standing outside said there was kids still inside so I went right up the ladder.”

Walter Cobe is 53 years old. He is a firefighter. Saturday afternoon, he was driving Jack Brennan, a deputy fire chief, when flames and smoke swallowed a house on River Street between Mattapan and Hyde Park and killed three children. This is his story:

“I got to the third floor, the attic, and I saw the house had thermopane windows, replacement windows, and I said to myself, `This is going to be a bitch.’ Replacement windows are thick and they hold all the heat in.

“I wasn’t wearing my helmet and facepiece. Just a mask. Air mask, and I had to take that off to get inside the attic because the window was so narrow.

“I got in and dropped to the floor right away. The smoke was tremendous. The visibility was maybe 6 inches. I put my unit back on and went to the wall. You stay close to the wall. You crawl on the floor on your hands and knees along the wall and feel for an opening. Maybe it’s a closet. Maybe it’s a bedroom. If you go in and feel clothes hanging, you know it’s a closet. You want to be able to get back out. You think of that. You don’t have a string attached to your back, you know.

“I met Tommy Blake inside. He’s from Ladder 16. He had come up the stairs. He was on the floor with me. It was like crawling down the lane of a bowling alley because I didn’t know if we’d ever get to the end. I said to Tommy, `Follow me.’

“I felt a bed and I turned my light on. The light is attached to your coat. Tommy and me, we felt on top of the mattress to see if any kids were on the bed. Sometimes kids go to the bed, hide under it because they think they’ll be safe, but there was only clothes and blankets on it.

“I said to Tommy, `We gotta get the mattress off. Help me flip it.’ We flipped it over. We couldn’t see anything at all, the visibility was so bad.

“I took my facepiece off so I could see better and felt the floor under the bed. I felt a hand and I said, `Tommy. I’ve got something here.’ At first I thought it was a woman, but it was two little children. They had been hugging each other, holding on to each other. I said, `Tommy. This is a kid.’

“Tommy got the hands and I took the feet. I said, `Tommy, can you handle the baby?’ and he said he could. He grabbed the child and went to the window where {Ladder Company} 28 had thrown up a 35-foot ladder. Tommy was doing mouth-to-mouth, then he handed the baby to Hansy, Hansy Rigueur. He’s Haitian. He was at the top of the ladder.

“Tommy’s air had run out. They say you have 15 minutes in a bottle but when you set your mask to `Purge’ and you’re really working, the air can go in five minutes. You know it because the vibra-alert in the mask goes off. You can feel it and hear it.

“When Tommy went to the window, I felt around some more and I felt a foot, a small one, then a little leg. I shined the light on it and I saw it was one of the boys. I still had my mask off and I was starting to get woozy. My oxygen had run out.

“I picked him up, stood up and went for the wall because I knew there was a stairway out there somewhere and I wanted to save the boy. Bobby Driscoll was still in the room. He’s from the Tower Unit. He kept on looking. You have to keep looking.

“There was a crib, a bed, some clothes piled up in the corner. That’s about all, but you have to go through everything. I carried the boy on my shoulders and started for the stairs. I felt this was the quickest way out, back down through the fire. Vern McEachern from Engine 53 was on the stairs and I said, `Vern. I’ve got a baby here.’

“Vern took his mask off and gave it to me. He grabbed me by the front of my coat and he started yelling, `Move out. Move out. We got a kid. We’re coming down.’ He never let go of my coat. I said, `Vern. Take the kid. I’m losing it. I don’t want to drop the kid.’ Vern pulled me down the steps and made sure we didn’t trip on any of the hoses or anything.

“We got outside and I gave the boy to the EMTs. Right after I came out, a policeman came running by me holding the boy Bobby Driscoll found. I think the policeman was either Mike Linskey or Kevin Welsh. They did a tremendous job.

“The boy was 4 feet from the other two kids. I think one of the boys took his sister out of the crib and dragged her under the bed. But you couldn’t see, the smoke was so thick. I feel badly they died. God knows, we tried to save them.

“Outside, I got treated for the smoke. The EMTs gave me some air. I laid down on a stretcher for five minutes. Then I got up and went back in, went back to work.”

According to the Fire Department, the fire was sparked by crudely installed illegal wiring in the basement where there was an illegal apartment. There was no smoke detector in the cellar. None could be found in the first-floor kitchen. The second-floor detector had dead batteries and did not work. On the third floor — the attic where the children lived — the detector functioned, but two boys, 5 and 2, died along with their sister who was 7. Twenty-seven people had been living in the house. The record shows the Boston Fire Department responded in less than four minutes.

Harold Brown, 73, was walking up River Street with his two great-grandchildren Saturday afternoon when he saw the first truck arrive from Cleary Square. Yesterday, he said: “I saw one fireman jump off the truck when it was still rolling to a stop. He didn’t even have his coat on yet, but he ran up and crashed right through the door into the fire because people were yelling kids were inside. I was in awe. I have never seen such bravery in all my life.”

Walter Cobe, 53, has been on the job 21 years. Saturday, with no questions asked and not a moment’s hesitation, he was one of many who crawled through thick smoke and fire, on hands and knees, without air, looking for lost children. Last week, his take-home pay after deductions was $377.

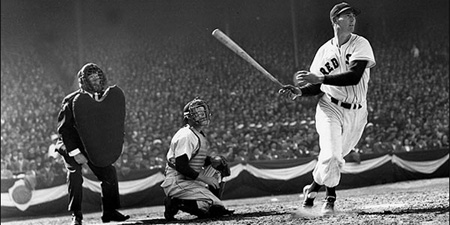

When the old man swung the imaginary bat through the fresh air of a clear, sunlit afternoon, the weight and dust of all the years fell away like marbles toppling off the edge of a three-legged table. Adults clapped. Little kids hung from the rail and sat atop a parent’s shoulder. Some men and women, of a certain age, and with a certain look to them, even cried.

The swing was still smooth as tap water tumbling from a faucet on the hottest of August days. The hips turned perfectly and the huge hitter’s hands rolled right over. The bulk of seven decades didn’t even show through the old man’s sports jacket because all anybody really saw was the number 9.

It seems odd, maybe even sacrilegious, to call him an old man because he lives beyond any calendar. Birthdays do not matter. When you are Ted Williams, nobody adds up the years.

I first saw Ted Williams in 1951. He was part of a pretty good team that could never quite catch the Yankees. When I shut my eyes, his swing at Fenway Park Sunday is the same swing I recall across all the vanished decades.

I first met Ted Williams in 1953. It was the year he returned from Korea. He did not have post-traumatic stress disorder. He did have 13 home runs and, once in awhile, if you waited long enough, you could catch him behind the old Somerset Hotel on Commonwealth Avenue.

In those days, I had very little idea what he might be doing inside the Somerset. Eating there? Living there? Who knew? All I knew was that rumor was the currency of youth and if there was even a whisper that Ted was around the hotel, the stakeout for autographs would begin.

There was no television then. Drugs and guns were unheard of to us, perhaps preposterous myths to older people. The few gangs that did exist were a collection of unemployed guys with duck-tail haircuts and pegged pants. Parents let kids ride trains, buses and trolleys around town with not a second thought given to safety.

We would go the ballpark in clumps. Sometimes we’d go to Braves Field, but more likely it was Fenway because that’s where the greatest hitter in the history of the game lived.

And Fenway became our church. Just as there was a downstairs 8 o’clock children’s Mass each Sunday in the parish, there was mandatory seating at the park: As close as you could get to the sloping left field rail where No. 9 prowled below.

He was then — and is now — larger than life. Unlike so many others — politicians, actors, statesmen, teachers, scientists, war heroes — time has not shrunk or sullied Ted Williams.

And Sunday, when they commemorated the fact that it is 50 summers since he hit .406 (and since Joe DiMaggio hit safely in 56 straight baseball games), you could hear the ballpark talk. Oh yes, ballparks do have voices, and they’re filled with memory and emotion.

I heard it. I think a lot of others did, too. And I’m sure Ted Williams heard it because it nearly caused him to cry in full view of all those strangers.

The ballpark spoke about The Kid from San Diego who hit .400 in that year of lost innocence. We were on the threshold of a war that would change America forever but, back then, baseball was our best seller, a story people bought and talked about every day, a tale told from radios perched on a thousand windowsills as a million men, women and children gathered on stoops and porches, following the action.

Ted Williams is that time. Ted Williams is that country. Other heroes have come and gone. The violence of the brutal years defeated a lot of dreams, but Ted Williams remains. Still looking like . . . well, Ted Williams.

Why has he survived? Simple: He could do whatever it was that needed to be done. You need a guy to hit .388 with 38 home runs? No problem. You need a man to sit in the cockpit of a fighter plane and protect democracy? You need someone to make sure John Glenn doesn’t get killed in Korea before he flies into outer space. Are you looking for a straight-talking, truth-telling, uncomplicated, no bee-essing, get-it-done, old fashioned, can-do, American kind of guy. Meet No. 9.

Baseball is a funny thing. It’s bigger than just a game. It has all these memories and stories attached to it, which makes it truly unique. Who tells football or basketball stories? What kid really has an indelible hockey memory?

Sunday, you could see — really see — through the fog of those long-gone summers. And you could hear — absolutely hear — the ballpark talk when Ted Williams stepped to the microphone, The Kid come home.

Then he took that swing. Spoke a few words. Tipped his cap. Glanced around, eyes repelling tears of current gratitude and nostalgic regret. There he was, legend married to magic: Ted Williams, up there for all the kids who ever were. He is the man who made summer last forever.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction or distribution is prohibited without permission.

Abstract (Document Summary)

I first saw [Ted Williams] in 1951. He was part of a pretty good team that could never quite catch the Yankees. When I shut my eyes, his swing at Fenway Park Sunday is the same swing I recall across all the vanished decades.

Ted Williams is that time. Ted Williams is that country. Other heroes have come and gone. The violence of the brutal years defeated a lot of dreams, but Ted Williams remains. Still looking like . . . well, Ted Williams.

Then he took that swing. Spoke a few words. Tipped his cap. Glanced around, eyes repelling tears of current gratitude and nostalgic regret. There he was, legend married to magic: Ted Williams, up there for all the kids who ever were. He is the man who made summer last forever.

WE DIED FOR THE 4TH OF JULY

THE BOSTON GLOBE

July 5, 1987

It’s the Fourth of July weekend. A time when much of America marches and sings and stops to do all sorts of different things for all kinds of reasons.

Where are you today? At the beach? On the front step? Down the Cape? Up in Vermont? Just sitting around the house hoping the sun will clear that clutter of clouds and provide you with the gift of a fine summer’s day? What are you doing? Making plans to have a cookout? Looking for your bathing suit? Cranking up a lawn mower? Sleeping late? Working maybe? Still talking about the parade or the fireworks that shattered the night sky? Monitoring kids as they move through the kitchen like troops on maneuver, all the while ignoring your questions about what they’re going to do and where they’re going to go?

Maybe you’re alone? Maybe you’re far from that particular place you might call home? Maybe you’re simply looking for a quiet spot where the breeze blows for you alone and the heat can never wound or stifle?

That’s where I live, in a sanctuary of private peace. A place that proves what life merely hints at: Death is the ultimate democracy, and all of those who are here with me this morning died, in a sense, for the Fourth of July.

Make no mistake, there are all kinds of people here with me. And they come from every part of the land you walk today: From the hill country of Tennessee, from the big industrial cities of the Midwest, from Boston, from Valdosta, Ga., and Culpepper, Texas, and Bellflower, Calif., Brooklyn, N. Y., too.

We are black and white and brown, and mostly young forever. That’s because we died during the permanent season of youth. We fell at places such as Okinawa and Anzio, by the Bay of Masan in Korea, along rocket-scarred ridges at Hill 881 South, looking through the mist toward the Laotian border, and in Grenada and Beirut as well.

We died for the Fourth of July!

It’s funny, but more than Memorial Day, more than November 11th, we always hope that who we were and what we did will be recalled at this time of year. Perhaps that’s because it is the lush edge of summer, a time when wounds seem remote and the concept of death is a stranger.

Shut your eyes for just a second and you’ll be able to see us, to hear us, too. We come from your hometown. You knew us. And, if you think about it for a minute, you can easily remember.

See that fellow over there? Well, on the Fourth of July, 1943, he was playing sandlot baseball in Clinton, Massachusetts. One year later, he took up residence with us because he had been claimed by a sniper’s bullet as he walked a hedgerow in Normandy.

Do you recall the fat kid who always made you laugh by turning on the hydrants and getting the cops mad during that hot summer of 1950 when the temperature was an unyielding adversary? He’s here. Been with us since Inchon.

And those boys who graduated from high school with you? Those kids with long hair and dreams of a decent future lived in a land that asked where Joe DiMaggio had gone and turned its lonely eyes to him? All those young men? They’re here, too.

They came over the course of a tortured decade, in a long proud parade — in numbers that never seemed to quit — from the A Shau valley, from Con Thien, from Camp Carroll and other miserable places that were quickly shuttled off to the shadows of history because America had chosen to become a land of living amnesiacs. But we remember.

We remember the hopes and dreams we had. We remember the families we left behind and the families we hoped to have someday.

We were poets and shortstops, schoolteachers and longshoremen, storekeepers and firemen, husbands, fathers, sons, lovers. Some of us were born rich. Some poor. Some knew glory before our last zip code was carved in stone. Some knew abuse and prejudice and the strictures of class.

Yet none of that matters now because there is no hate here. No unreasoning racism. No fits of temper, outrage or revenge. Not even much memory. Here, summer is forever.

Don’t feel badly for us, though, because we are the lucky ones. We don’t worry about the world ending in a single flash of agony caused by ignorance and unreason. We don’t have to be concerned about the steady tide of poverty, the ocean of drugs, all the lost sense of history or the victory of money over the elements of compassion and justice.

We are beyond all of that. Above it really. Because we are all dead now. And we died for the Fourth of July.

It’s the Fourth of July weekend. A time when much of America marches and sings and stops to do all sorts of different things for all kinds of reasons.

Where are you today? At the beach? On the front step? Down the Cape? Up in Vermont? Just sitting around the house hoping the sun will clear that clutter of clouds and provide you with the gift of a fine summer’s day? What are you doing? Making plans to have a cookout? Looking for your bathing suit? Cranking up a lawn mower? Sleeping late? Working maybe? Still talking about the parade or the fireworks that shattered the night sky? Monitoring kids as they move through the kitchen like troops on maneuver, all the while ignoring your questions about what they’re going to do and where they’re going to go?

Maybe you’re alone? Maybe you’re far from that particular place you might call home? Maybe you’re simply looking for a quiet spot where the breeze blows for you alone and the heat can never wound or stifle?

That’s where I live, in a sanctuary of private peace. A place that proves what life merely hints at: Death is the ultimate democracy, and all of those who are here with me this morning died, in a sense, for the Fourth of July.

Make no mistake, there are all kinds of people here with me. And they come from every part of the land you walk today: From the hill country of Tennessee, from the big industrial cities of the Midwest, from Boston, from Valdosta, Ga., and Culpepper, Texas, and Bellflower, Calif., Brooklyn, N. Y., too.

We are black and white and brown, and mostly young forever. That’s because we died during the permanent season of youth. We fell at places such as Okinawa and Anzio, by the Bay of Masan in Korea, along rocket-scarred ridges at Hill 881 South, looking through the mist toward the Laotian border, and in Grenada and Beirut as well.

We died for the Fourth of July!

It’s funny, but more than Memorial Day, more than November 11th, we always hope that who we were and what we did will be recalled at this time of year. Perhaps that’s because it is the lush edge of summer, a time when wounds seem remote and the concept of death is a stranger.

Shut your eyes for just a second and you’ll be able to see us, to hear us, too. We come from your hometown. You knew us. And, if you think about it for a minute, you can easily remember.

See that fellow over there? Well, on the Fourth of July, 1943, he was playing sandlot baseball in Clinton, Massachusetts. One year later, he took up residence with us because he had been claimed by a sniper’s bullet as he walked a hedgerow in Normandy.

Do you recall the fat kid who always made you laugh by turning on the hydrants and getting the cops mad during that hot summer of 1950 when the temperature was an unyielding adversary? He’s here. Been with us since Inchon.

And those boys who graduated from high school with you? Those kids with long hair and dreams of a decent future lived in a land that asked where Joe DiMaggio had gone and turned its lonely eyes to him? All those young men? They’re here, too.

They came over the course of a tortured decade, in a long proud parade — in numbers that never seemed to quit — from the A Shau valley, from Con Thien, from Camp Carroll and other miserable places that were quickly shuttled off to the shadows of history because America had chosen to become a land of living amnesiacs. But we remember.

We remember the hopes and dreams we had. We remember the families we left behind and the families we hoped to have someday.

We were poets and shortstops, schoolteachers and longshoremen, storekeepers and firemen, husbands, fathers, sons, lovers. Some of us were born rich. Some poor. Some knew glory before our last zip code was carved in stone. Some knew abuse and prejudice and the strictures of class.

Yet none of that matters now because there is no hate here. No unreasoning racism. No fits of temper, outrage or revenge. Not even much memory. Here, summer is forever.

Don’t feel badly for us, though, because we are the lucky ones. We don’t worry about the world ending in a single flash of agony caused by ignorance and unreason. We don’t have to be concerned about the steady tide of poverty, the ocean of drugs, all the lost sense of history or the victory of money over the elements of compassion and justice.

We are beyond all of that. Above it really. Because we are all dead now. And we died for the Fourth of July.

BOSTON GLOBE

April 13, 1986

Baseball is a game of memory, and it returns tomorrow to a place where grass has not yet given way to a carpet. It comes home to a green haven filled with reminders of both heartbreak and happiness, a ballyard called Fenway Park where the cargo of past athletic time refuses to yield to sports’ current themes of greed and arrogance.

Baseball is a mood, a suggestion of sunshine and subway stops that all seemed to lead to Section 16. Once, it was truly the city game, truly America’s pastime and certainly the one sport that bound generations together. Fathers sat with sons and daughters and shared the mellow remembrances of other Opening Days played in earlier, easier afternoons before night stole the game. Then, the shadows of history and reality could be shuffled effortlessly around like so many boxes filled with relics of youth on moving day.

And the stories never had to be anchored in fact. As the calendar moved forward, hits, runs and errors became less important. Mood and memory prevailed.

There, right over there behind the dugout, is where Teddy Ballgame’s bat landed after he threw it in disgust and it hit Joe Cronin’s housekeeper. And do you see the first-base coach’s box? That’s where Dick Stuart bent down to pick up a hot dog wrapper and got a standing ovation because it was the only thing he ever picked out of the dirt with his glove.

The park still rumbles with the aftershock of visions long since gone: Shut your eyes and Joe DiMaggio is still making his last appearance in Fenway. Jimmy Piersall is still squirting home plate with a water pistol. Tony C. is down in the dust, and the crowd’s deathly silence still makes a noise in your mind.

Don Buddin can reappear at any moment. Within your own personal game, Rudy Minarcin, Matt Batts, Jim Mahoney, George Kell, Billy Klaus, Jerry Adair, Clyde “The Clutch” Vollmer, Rip Repulski, Mickey McDermott and Gene Stephens can be the components of your bench.